Introduction

In Australia, approximately 20,000 breast cancer diagnoses are made annually.1 On average, each year 4000 patients undergo mastectomy as part of their treatment.2 Australian national and surgical society guidelines recommend all women undergoing mastectomy are offered the opportunity to discuss breast reconstruction prior to surgery.3,4 The proportion of patients undergoing breast reconstruction post-mastectomy surgery has risen from 12.8 per cent in 2010 to 29 per cent in 2019.2

The COVID-19 pandemic changed surgical oncology and patient management around the world.5 The need to prioritise healthcare resources and limit patient (and healthcare worker) exposure to COVID-19 in the healthcare setting resulted in changes to local practices. The impact this had on mastectomy and breast reconstruction rates has been documented in many countries, including the United States, Canada, Scotland and Pakistan.6–9 However, there is a paucity of information on how the COVID-19 pandemic altered mastectomy and reconstruction rates in Australia.

The primary aim of this study was to review and compare the practice of post-mastectomy breast reconstruction in a busy metropolitan hospital before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Breast cancer types and resection rates before and during the COVID-19 pandemic were reviewed, and the short- and long-term complications over the combined period were also evaluated.

Methods

We conducted a single centre retrospective comparative review of patients who underwent breast reconstruction between April 2018 to March 2020 inclusive (24 months, pre-COVID-19) and April 2020 to March 2022 inclusive (24 months, COVID-19) at Western Health (Melbourne, Australia). Western Health is a metropolitan service that provides healthcare for a catchment population of 890,000 (a population that increased by 8.6 per cent between 2018 and 2021).10 Our health network provides a multidisciplinary oncological breast service (including resection by the breast surgery team and reconstruction by the plastic surgery team). During COVID-19, there were no restrictions on the admission of unvaccinated patients for elective surgery.

All patients who underwent one or more of the following procedures during the study period were included:

-

breast-conserving oncological procedures (eg, wide local excision [WLE], lumpectomy)

-

mastectomy (including nipple-sparing, skin-sparing and total mastectomy—any indication)

-

autologous and/or alloplastic breast reconstruction.

Cases were identified through our hospital breast cancer database and cross-referenced with our weekly surgical audits. Data collected includes patient demographics, oncological attributes, surgical management and outcomes.

Data was summarised based on patients (rather than number of breasts) and analysed using GraphPad Prism (version 9.4.0 for Mac, Graphpad Software, Boston, USA). Continuous data was analysed using unpaired t-test. Categorical data in contingency tables was analysed using Fisher’s exact test, and chi-square test for three more categorical outcomes. A p-value < 0.05 was determined to be statistically significant. Quality assurance approval was obtained from the Western Health Office for Research (Quality Assurance Project Number: QA2022.72) before the commencement of this study. It was considered exempt from ethics review.

Results

Background and demographics

A total of 488 patients who underwent oncological breast surgery were included in the analysis. The number of patients were similar between the two study periods (240 before versus 248 patients during the pandemic, p = 1.0). There was a statistically significant increase (p < 0.001) in the number of patients undergoing mastectomy compared to WLE or lumpectomy during the COVID-19 pandemic (113 of 248, 45.6%) compared to before COVID-19 (73 of 240, 30.4%), Comparing the two study periods, patients who underwent mastectomy and reconstruction were similar in age, type of mastectomy, number and types of adjunct and contralateral procedures, and pathology (Table 1). There was no difference in the number of contralateral prophylactic surgeries during the COVID-19 pandemic (16 of 248, 6.5%) compared to before COVID-19 (8 of 240, 3.3%, p = 0.15).

Reconstruction

Post-mastectomy reconstruction rates were similar before and during the COVID-19 pandemic (p = 0.68, Table 2). Furthermore, the timing and type of reconstruction were also similar between the two periods.

A total of 109 patients underwent a reconstructive procedure (first or second stage) during the study period. Forty-five before the COVID-19 pandemic and 64 during the COVID-19 pandemic. Types of reconstruction are summarised in Table 3. In the pre-COVID-19 period, there were 153 face-to-face consultations and no telehealth consultations in the three-month postoperative period. During the COVID-19 pandemic, 258 face-to-face and five telehealth consultations took place in the three-month postoperative period (face-to-face 100% pre-COVID-19 versus 98.1% during COVID-19, p = 0.16). This equates to a mean of 3.4 postoperative reviews per patient pre-COVID-19 and 4.1 postoperative reviews per patient during the COVID-19 pandemic (p = 0.09).

Complications

There were 16 short term (< 6 weeks) and five long-term (≥ 6 weeks) Clavien–Dindo classification 2 and higher breast-related complications. Overall, there was no difference in complications between the two study periods (p = 0.09, Table 4).

Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic created many challenges in resource allocation and use of healthcare resources internationally. The Australian state of Victoria experienced three major waves during the first two years of the COVID-19 pandemic leading to a reduction in elective surgery (including oncological surgery and reconstruction). This resulted in surgical waitlists doubling between March 2020 and March 2022.11 Victoria faced some of the harshest restrictions in patient mobility and care, and Melbourne was Australia’s most locked down capital city during the COVID-19 pandemic (267 days).11 The intended effect of these lockdowns was to have overall low community COVID-19 case numbers during the first 18 months of the COVID-19 pandemic study period. As a result, our centre had limited experience of patients undergoing breast reconstruction who were COVID-19 positive during the perioperative or postoperative period.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the proportion of mastectomies in our centre significantly increased from 30.4 per cent to 45.6 per cent without a change in underlying pathology (ie, invasive or in situ disease). This increase in mastectomy rate was potentially due to two reasons. First, a more aggressive surgical approach (mastectomy) and aversion toward breast-conserving therapy reduced the associated need for adjuvant therapy (particularly radiotherapy) and exposure of patients to the healthcare system during adjuvant therapy. This helped to conserve hospital resources, lessened staffing requirements, reduced the possibility of staff exposure to patients with COVID-19 and protected non-infected patients from other patients being treated for COVID-19. However, this may be confounded by changes in the surgical management of breast cancer with changes in neoadjuvant chemotherapy and de-escalation protocols as well as the further subspecialisation of breast surgeons. The second explanation is a later disease presentation (eg, from delayed screening or difficulties in accessing primary healthcare) resulting in higher invasive rates. While there was no change in the underlying pathology of in situ compared to invasive disease for patients who underwent reconstruction, this may explain the increase in mastectomy rates.

Despite the logistical challenges and poorer access to surgery resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic, breast reconstruction remained a priority. The reconstruction rate during the COVID-19 pandemic (46%) was comparable to our pre-COVID-19 rate of 39.7 per cent and above the Australian metropolitan pre-COVID-19 average of 33.1 per cent.2 This was achieved through collegial collaboration between breast surgery and plastic surgery units, integrated breast cancer nurses, and a focus on reducing hospital length of stay and maintaining access to postoperative reviews. Bookended by the lack of local, state, federal or surgical society policy or guideline to limit reconstructive services, at our healthcare service we did not shirk the professional obligation to consider that healthcare resources were being used appropriately. Instead we continued to weigh our local resources against the positive psychological benefits of immediate breast reconstruction.12

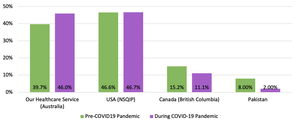

In our centre, implant-based and two-stage breast reconstruction rates remained similar between the two study periods, in contrast to national and international data (Table 2). According to national data published by the Australian Breast Device Registry (ABDR), there was a decrease in the number of tissue expander insertions compared to direct-to-implant (DTI) breast reconstructions.13 The ABDR reports that between 2016 and 2019 the proportion of tissue expander insertion was stable at 50 to 52 per cent. In 2020, this dropped to 42 per cent, then to 38 per cent in 2021 with a corresponding rise in DTI. The national increase in DTI may in part be due to reduced access to postoperative reviews during the COVID-19 pandemic. We did not experience an institutional push in limiting access to clinic reviews and thus maintained our rate of postoperative reviews—potentially contributing to our steady rate of autologous reconstruction. Internationally, the United States (based on data from the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program [NSQIP]) maintained their breast reconstruction rates during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic.7 The authors of this study believed the high rates of reconstruction (comparable to Australia) persisted due to the psychological benefit of breast reconstruction to patients. The authors also echoed the views of other studies that recommended continuing reconstruction to avoid increasing the burden on the healthcare system of patients requiring delayed reconstruction.14 However, the slight rise in tissue expander insertion (from 64% to 68%)7 between 2019 and 2020 in the USA, and the drop in reconstruction in countries such as Canada (British Columbia)9 and Pakistan8 (Figure 1), may indicate this will be a future challenge. In combination with some regions offering no immediate reconstruction in early lockdowns,6 the effects of reduced reconstruction rates (resulting in delayed or no reconstruction) are yet to be studied and may still be unknown for many years to come.

There were comparable overall rates of breast complications pre-COVID-19 and during the COVID-19 pandemic. There were concerns that complication rates would increase during the COVID-19 pandemic. Contributing factors included pressures on surgical time, earlier discharges and lack of access to the treating team after discharge due to patient reluctance to attend the emergency department and the transition to telehealth consultations. Notably, three patients had seromas requiring intervention and they all occurred in the COVID-19 period. A propensity to remove surgical drains earlier to facilitate hospital discharge or reduce home visits from our Hospital in the Home program may have contributed. All four late infections occurred in the COVID-19 pandemic period and between six and 12-months postoperatively. It is unlikely these infections could have been averted in the pre-COVID-19 pandemic period. However, earlier identification may have resulted in more aggressive treatment and salvage of the three implants lost to infection.

Limitations of this study include the study design being a retrospective single centre review within the context of geographical COVID-19 restrictions and case numbers. As a higher volume service, we may have been less susceptible to changes in local hospital conditions (eg, low volume services may be the first to be ‘sacrificed’ in the reallocation of resources). COVID-19 may have also artificially increased our proportion of mastectomies compared to breast-conserving therapy (from 30.4% to 45.6%). We are also not able to delineate patient and clinician decisions for resection type (eg, because of changes in surgical oncological care, histological subtype or choosing a mastectomy to avoid radiotherapy). Future studies could be directed at determining if the increase in mastectomy rate is sustained in a post COVID-19 era. This may indicate whether the increase in mastectomy rate is due to clinician bias, temporary and largely due to the COVID-19 pandemic, or reflects true changes in oncological management of breast cancer. Research could also be conducted within healthcare services that experienced reduced reconstruction rates due to the COVID-19 pandemic with a focus on the psychological impact on patients and the practical effect on healthcare service delivery. This may help in determining the alternate cost of not attempting to maintain reconstructive services during a pandemic.

Conclusion

This is the first study to present the changes in breast reconstruction in Australia during the COVID-19 pandemic. In our multidisciplinary single centre experience, despite increased mastectomy rates during the pandemic compared to breast-conserving therapy, breast reconstructive services were safely maintained above national and international rates—without an increase in complication rates. This was achieved via collaboration, communication and early discharge.

Patient consent

Patients/guardians have given informed consent to the publication of images and/or data.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding declaration

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Revised: March 30, 2024 AEST