Introduction

War is the only proper school for surgeons.

—Hippocrates (ancient Greek physician)

How fertile the blood of warriors in raising good surgeons.

—Sir Clifford Allbutt, 1836–1925

Despite being the most distant realm of the British Commonwealth from Europe, New Zealand has always maintained a strong bond with the United Kingdom. This bond has led to military support for Britain in both the first and second world wars.

The story of New Zealand’s pioneers in plastic surgery had its origins in the theatres of war surgery, especially World War I (WWI). The trench warfare presented huge numbers of mutilating facial injuries, the severity of which had seldom been seen in the past and never before in such numbers.

Late nineteenth century and pre-WWI

The New Zealand plastic surgery story begins in the southern city of Dunedin (Gaelic for ‘Edinburgh of the South’) with the departure of New Zealand-born Harold Gillies for England in 1902 and the arrival in New Zealand, five years later, of English born Henry Percy Pickerill from Birmingham.

Harold Delf Gillies (1882–1960)

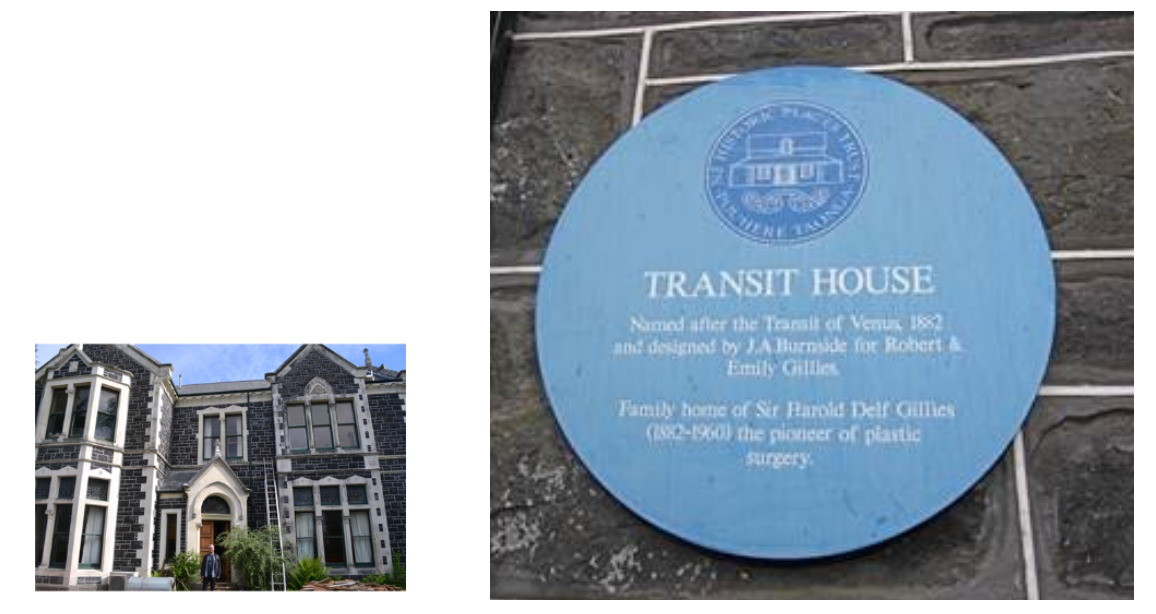

Harold Gillies was born in the family home, Transit House (Figure 1), 44 Park Street, Dunedin, in 1882. After attending preparatory school in England, he returned to New Zealand and was an outstanding student at Wanganui Collegiate School. In 1902 he won a scholarship to Cambridge University where he studied medicine at Gonville and Caius College, then later at St Bartholomew’s Hospital in London. He completed his medical degree in 1906 and his Fellowship of the Royal College of Surgeons (FRCS) in 1910. After holding posts at ‘Barts’ he trained as an otorhinolaryngological (‘ENT’) surgeon.

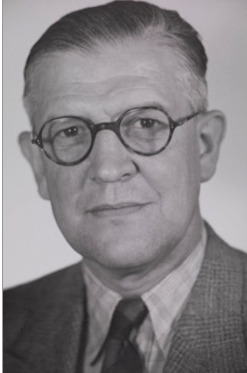

Following the outbreak of WWI, Gillies (Figures 2 and 3) was sent to France by the Red Cross to work as a General Surgeon. His work and contacts in France eventually led to the establishment of British plastic surgery.

He read the work of August Lindemann (1880–1970) of Dusseldorf on jaw fractures and wounds around the mouth—‘My first inspiration came from the few pictures in that German book’—and discovered the book La Rhinoplastie (1907) written by French surgeons Charles Nélaton (1851–1911) and Louis Ombrédanne (1871–1956).

His work with Major Sir Auguste Charles Valadier (1873–1933), a colourful Franco-American dentist who had already completed more than 1,000 facial reconstructions, and Hippolyte Morestin (1869–1919), a Parisian plastic surgeon, gave him ‘a tremendous urge to do something other than the surgery of destruction’.

Later he became aware of other facial reconstructive work being done in Europe, and communicated with Jan FS Esser (1877–1946) of the Netherlands and Jacques Joseph (1865–1934) of Berlin.

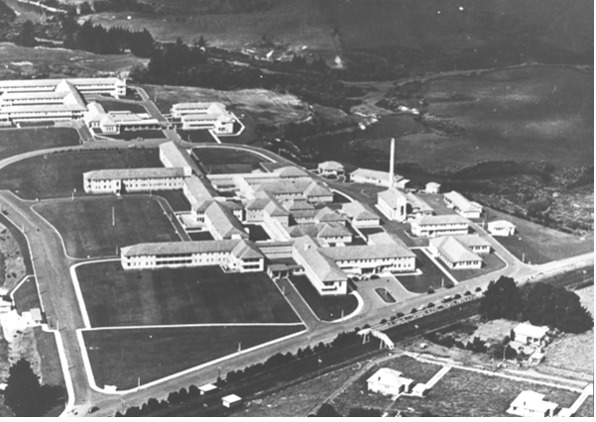

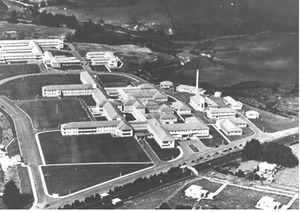

Following his return to England in 1916, ‘for special duty in connection with plastic surgery’, Gillies established a maxillofacial centre at Cambridge Hospital, Aldershot, and then worked in a purpose-built hospital at Sidcup, in Kent (Figure 4).

The Queen’s Hospital at Sidcup was divided into five sections: two for UK surgical teams and one each for Australia, commanded by Lt Col Henry Newland, Canada under Captain Fulton Risdon, and New Zealand under Major Percy Pickerill. A number of American surgeons, including George Dorrance, Ferris Smith and Vilray Blair, later joined the surgical teams.

Gillies was the mastermind at Sidcup. He had enormous foresight, courage, a strong personality and tremendous organisational skills.

Many principles and innovations that evolved from the Sidcup experience we now take for granted. These included the involvement of dental specialists, the multidisciplinary team approach, and the importance of accurate records, including medical photography, artist’s drawings and plaster casts (Figure 5). He acknowledged that skilled anaesthesia and specialist nursing were equally important for successful reconstructive surgery.

Henry Percy Pickerill (1879–1956)

Percy Pickerill (Figure 6) was born in Hereford, England, in 1879 and studied medicine and dentistry at Birmingham University, where he graduated in 1905. At the age of 28 he was appointed from five applicants to be the first director of the newly established School of Dentistry at the University of Otago in Dunedin. He quickly developed a national reputation for promoting dental health and developing maxillofacial surgery, including orthognathic and cleft palate surgery.

In December 1916, Major Pickerill (Figure 7) was sent to England to join the Second NZ General Hospital at Walton-on-Thames, where he established a unit for the treatment of facial and jaw injuries. During a royal visit by King George and Queen Mary to the hospital, the Queen persuaded Pickerill to move his unit to Sidcup. Pickerill’s team was assigned three wards and treated soldiers of all nationalities. With his dual medical and dental training and experience, Pickerill earned a well-deserved reputation as a first-rate plastic and maxillofacial surgeon. His forehead rhinoplasties (Figure 8) were praised by Gillies.

Sydney Devenish (Tommy) Rhind MC (1894–1956)

Rhind, who was born in Christchurch, was a medical graduate from University College Hospital, London. He had been gassed twice in WWI and was also a patient at the NZ General Hospital. Following his recovery, he became Pickerill’s assistant surgeon with the NZ section at Sidcup. After the war, he returned to New Zealand as a General Surgeon at Wellington and Hutt Hospitals (1924–1953).

Post-WWI Years

Following WWI, Gillies published Plastic surgery of the face, a comprehensive description of the treatment of facial injuries and the precursor to the first edition of his two-volume treatise Principles of plastic surgery. He continued treating wounded servicemen, and in his civilian practice confined his work to plastic surgery. He established a private practice at 7 Portland Place, London. It was 1930 before he obtained two dedicated public hospital beds at Barts. Between the wars, Gillies at first struggled but eventually succeeded in maintaining his new role as a plastic surgeon: ‘My surgery may not be life-saving, but it is life-giving’.

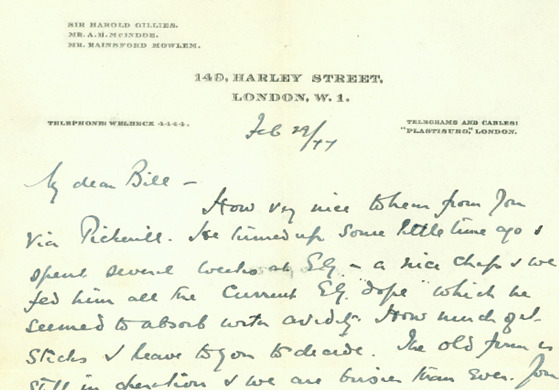

Gillies, who was knighted in 1930, had long wished to form his own clinic where he would lead an international centre of plastic surgery. In the early 1930s he was one of 36 physicians and surgeons who each invested £2,000 for the London Clinic and Nursing Home at 149 Harley Street. He made it his consulting headquarters, occupying a ground floor suite on a 25-year lease at comparatively low rent.

Pickerill returned to Dunedin where he completed reconstructions on New Zealand soldiers and resumed his work at the dental school and hospital. In 1924, Pickerill described his wartime experiences treating facial injuries and how he applied the lessons of war to civilian practice in a book titled Facial surgery.

He resigned his position as Dean of the Dental School in 1927 and moved to Sydney, Australia, to establish a plastic surgical practice. Cecily Clarkson (1903–1988), a talented former house surgeon and later Pickerill’s wife, joined him there. Initially Cecily assisted Percy, but he later trained her in cleft lip and palate surgery.

Thomas Noel Usher (1882–1950)

Usher was a New Zealander who had obtained dental and medical degrees from Edinburgh and Glasgow. On returning to New Zealand, he was appointed honorary Children’s Surgeon to Wellington Hospital. He was said to have pioneered cleft lip and palate surgery in Wellington.

New Zealanders in the UK, 1930s

As a small, remote country with a young medical school and a small population, New Zealand did not offer any postgraduate medical training. There was a public perception that further training in ‘the old country’ (United Kingdom) was essential to become a good doctor and advance one’s career.

Some, like Gillies, Usher, Rhind and Patrick Clarkson, travelled to the UK for their undergraduate training, with Rhind and Usher then returning to work in Wellington.

Others, like McIndoe (who initially obtained a scholarship to the Mayo Clinic, USA), Mowlem and Barron, travelled to the UK for their postgraduate training and remained in the UK.

Archibald Hector McIndoe (1900–1960)

McIndoe (Figure 9) was born and educated in Dunedin. He graduated in medicine from Otago University in 1923, with his friend, Arthur Porritt, and was a house surgeon at Waikato Hospital, Hamilton, in 1924. He then won a scholarship to the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota, USA, to study surgical pathology and hepatobiliary surgery.

Lord Moynihan, President of the Royal College of Surgeons, met McIndoe and was impressed with his work at the Mayo Clinic. He persuaded McIndoe to relocate to London with the promise of a professorship at the University of London. Unfortunately, this job did not exist. In London, Harold Gillies, his cousin, helped McIndoe to obtain the FRCS, train in plastic surgery and join Gillies in his private practice at 149 Harley Street.

Arthur Rainsford Mowlem (1902–1986)

Mowlem (Figure 10) was born in Auckland and graduated in medicine from the University of Otago in 1925 (the same year as Cecily Clarkson). He travelled to UK for postgraduate training and, after obtaining the FRCS, he was preparing to return to New Zealand when he was asked to act as a locum at Hammersmith Hospital to look after Gillies’ patients. He remained with Gillies for two years, moving with him and McIndoe to St James Hospital, Balham (the first public plastic surgery unit) and, also like McIndoe, later joined Gillies in private practice. Meanwhile, a young Australian house surgeon named Benjamin K Rank (1911–2002), keen on a career in plastic surgery, became their (Gillies’, McIndoes’ and Mowlem’s at St James Hospital, Ballham) first resident surgical officer in 1937.

John Barron (1911–1992)

Barron (Figure 11) was born in Napier, and graduated in medicine from the University of Otago in 1936. He travelled to the UK and, after completing his plastic surgery training, became first assistant to Mowlem at Hill End Hospital, St Albans. He and his wife lived in the seventeenth century home of the Canon of St Albans Cathedral, previously occupied by Benjamin Rank and his wife.

Patrick Wensley Clarkson (1911–1969)

Clarkson was born in New Zealand and travelled to UK for his medical training in Edinburgh and Guy’s Hospital in London. He undertook plastic surgery training under Gillies at Rooksdown House, Basingstoke.

Preparing for World War II

In the UK in 1938, with the prospect of another war looming, Gillies and his oral surgery colleague William Kelsey Fry (1899–1963) were tasked with planning a new military plastic surgery service. Realising that Sidcup lay under the potential route of bombers attacking London, they agreed to disperse the service. Gillies went to Basingstoke, taking over Rooksdown House at Park Prewett Mental Hospital; McIndoe set up at the Queen Victoria Hospital, East Grinstead; Mowlem went to Hill End Hospital at St Alban’s; and Kilner to Stoke Mandeville. Many emergency hospital service (EHS) facilities were built outside the larger cities, and many included faciomaxillary units.

Meanwhile in New Zealand, Percy and Cecily Pickerill had returned from Sydney in about 1935 and set up practice in Wellington. They took up appointments at Wellington Hospital, and worked on the establishment of Bassam, a private hospital dedicated to treating babies with cleft lip and palate.

World War II

On the outbreak of World War II (WWII), Pickerill wrote to the Director of Medical Services at NZ Defence Headquarters:

If you can utilise my services as a plastic surgeon in the present emergency, I beg to place them at your disposal.

His previous wartime experience was put to good use in the training of personnel of the Dental Corps.

Sir Harold Gillies, in a letter to the New Zealand Director General of Health in February 1940, offered to accept one or two suitable medical officers for special training in plastic surgery so that they might carry on the work for wounded NZ soldiers. This offer was accepted, with a senior post for a plastic surgeon to set up a military plastic surgery unit in New Zealand, as well as a junior position.

For the senior post, John Barron, then working as an assistant to Mowlem at St Albans, was considered too junior.

Joseph J Brownlee II (1902–1972)

Brownlee (Figure 12) was selected for the senior post with Gillies. His postgraduate experience in London had included three years with Percival Cole (1878–1948) at the Cancer Hospital. At the time, he was on the staff of the Christchurch Hospital as a General Surgeon, where he treated all plastic surgical patients. Upon selection he spent a year working with Gillies, McIndoe and Mowlem, then returned to Christchurch to set up a military plastic surgery unit at Burwood Hospital.

William Maxwell Manchester (1913–2001)

Manchester (Figure 12) was selected as the junior trainee under Gillies. He had graduated from the Otago Medical School in 1936 and, after a year as an anatomy demonstrator and in house surgeon positions, enlisted in the army in 1940 as a battalion medical officer.

He was sent to the Queen Victoria Hospital, East Grinstead, UK, arriving there on 9 December 1940. During his six months at East Grinstead, ward three had to be evacuated due to an outbreak of haemolytic streptococcus infection. On another occasion an unexploded bomb close to the hospital entrance required evacuation of all the patients. He was invited to join McIndoe to visit other hospitals in England to assess wounded servicemen for possible transfer to East Grinstead.

During this time saline baths were introduced for the management of extensive burns and tannic acid dressings were banned.

He attended lectures and clinics given by Gillies and later transferred to St Albans for further training under Rainsford Mowlem and John Barron.

After one year of plastic surgical training, his main teachers being New Zealanders, he was posted to the 1st New Zealand General Hospital in Helwan, Egypt. Here he created a Plastic Surgical Unit with his friend and dental colleague, Geoff Gilbert (Figure 12). He remained at this hospital for two years. During this time, he collaborated with the Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC) research section on treating burns and measuring blood sulpha levels in patients treated with topical sulphanilamide. Another New Zealander providing data on burns patients was General Surgeon Arthur Porritt (later Baron Porritt, Governor-General of New Zealand and President of the Royal College of Surgeons of England) then stationed in Egypt with the RAMC.

Manchester travelled back to New Zealand in 1944 to work at Burwood Military Hospital, where Major Geoff Gilbert, the father of Stephen Gilbert FRACS, was also on the staff.

Frank Leo Hutter (1910–1985)

Frank Hutter graduated from the Otago Medical School in 1935, before travelling to the UK for postgraduate experience. After enlisting in the Royal New Zealand Army Medical Corps (RNZAMC) from October 1940 to May 1941, he trained in plastic surgery at Hill End Hospital with Mowlem and Barron. He went on two tours of duty in Egypt, North Africa and Italy. Following the war he gained further surgical experience in London, spending time in plastic surgery at Queen Victoria Hospital, East Grinstead. He returned to Wellington to set up a plastic surgery unit at Wellington Hospital in 1947.

Brian John David Dunne (1903–1968)

Dunne was born in South Africa, educated in New Zealand, and graduated from the Otago Medical School in 1929. He travelled to the UK where he trained and worked in plastic surgery at the Dreadnought Seamen’s Hospital with Percival Pasley Cole (1878–1948). He enlisted in the New Zealand army and served in Egypt, Syria and Italy as a plastic surgeon. He was invalided out of the army in 1944 and returned to surgical practice in the UK.

Leslie John Roy (1913–1999)

Roy was born in New Zealand and graduated from Otago Medical School in 1937. He proceeded to the UK in 1939. Following a year as anatomy demonstrator in Glasgow, he worked in the Plastic Surgery and Facio-Maxillary Unit at Ballochmyle Hospital, Ayrshire for two and a half years. This was a newly built EHS facility, the forerunner of the Glasgow Regional Plastic Surgery service, and was visited regularly by Gillies.

Roy enlisted in the RNZAMC in February 1942, serving in North Africa and Italy, then had further training in plastic surgery at East Grinstead during 1944–1945. He returned to Christchurch to the Burwood Hospital Plastic Surgery Unit in 1947.

The University of Otago Medical School

While all the named surgeons had great intelligence, boundless energy and ambition, a common bond with most of them was their training at the Otago Medical School, Dunedin.

In the 1920s, McIndoe (graduated 1923), Mowlem and Cecily Clarkson, and later Pickerill, (1925), and Brownlee (1926) were possibly known to each other as students.

In the 1930s, Hutter and Barron (graduated 1935), Manchester (1936) and Roy (1937) would all have known each other. By this time, the medical school (Figure 13) had grown with the addition of a new building (Figure 14).

Plastic surgery in NZ during WWII

In New Zealand during WWII, Percy and Cecily Pickerill, who were both on the staff of Wellington Hospital, provided plastic surgery services. In addition, the Pickerills had established a private hospital named Bassam, in Lower Hutt. Here they treated most of the babies in New Zealand born with a cleft lip and palate. Some civilians underwent plastic surgery treatments in the Burwood military hospital.

Post WWII, UK

Following WWII, Gillies, McIndoe and Mowlem remained in the UK, still in partnership at 149 Harley Street, undertaking work at their wartime hospitals. Gillies and a young American surgeon, Ralph Millard (1919–2011), wrote The principles and art of plastic surgery (Figure 15).

After service in Yugoslavia, helping to set up a hospital for plastic and reconstructive surgery in Belgrade in 1945, John Barron worked at Rooksdown House with Gillies before moving to Salisbury to establish the Wessex Plastic Surgery Service in 1949. He served terms as President of the British Association of Plastic Surgeons, and also the British Society for Surgery of the Hand. He was the senior author of a three-volume textbook, Operative plastic and reconstructive surgery in 1980, initiated the British Association of Plastic Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgeons (BAPRAS) Barron Prize and had an enviable reputation as a world leader in plastic surgery. In 1975 he received Yugoslavia’s highest award; the Yugoslav Flag with Golden Wreath.

Patrick Clarkson returned from military service in North Africa to Guys Hospital, wrote a book on hand surgery with Australian surgeon Anthony (Tony) Pelly (1909–1982), and described Poland syndrome, named after British surgeon Sir Alfred Poland (1822–1872).

All continued to train plastic surgeons and took a special interest in young New Zealand and Australian plastic surgery trainees.

Post WWII, New Zealand

The Pickerills continued their work at Bassam. Before the establishment of regional plastic surgery units, they treated most of the babies born in New Zealand with cleft lip and palate. They pioneered the concept of mothers nursing their babies following surgery and demonstrated a very low incidence of cross-infection in their hospital. In 1977, Cecily Pickerill (Figure 16) was made a Dame Commander of the British Empire for her services to medicine.

Regional plastic surgery units

Christchurch

Major Joseph Brownlee and Major Geoff Gilbert established the Christchurch RPS at Burwood Hospital in 1943 as a Specialist Military Plastic Surgery Unit for treating wounded servicemen.

Jack Smith (the father-in-law of Michael Klaassen, one of the authors of this article) was a 19-year-old NZ naval rating and a patient at Burwood Hospital (1943). Following concerns that the orthopaedic surgeons were going to amputate Jack’s left leg for a chronic radiation ulcer (excessive radiation for a verucca!), Jack recounted that ‘the sister asked Joe Brownlee to come and see me and told me he could save my leg with a cross leg flap’. Jack went on to play rugby for North Auckland in the early 1950s.

Due to the large volume of work, Manchester was recalled from Egypt and he later replaced Brownlee as Surgeon-in-Charge, when Brownlee resigned to return to his private surgical practice (Figure 17).

After WWII, Manchester was invited to convert the military unit into a 60-bed civilian plastic surgery unit. One of his house surgeons in 1947 was Desmond (Des) Kernahan MBChB (1921–1999), who trained in plastic surgery, became a consultant in Liverpool, and later worked in Winnipeg and Chicago.

Brownlee and Roy replaced Manchester in 1948. Following Brownlee’s retirement in 1955, John Roy became head of department (Figure 18).

Tom Milliken (1925–2015), who had graduated from the Otago Medical School in 1949, assisted Roy. By then Milliken had travelled to the UK for postgraduate experience, obtaining the FRCS in 1955. Following plastic surgery training at East Grinstead, he returned to Christchurch to an appointment at Burwood Hospital, where he remained until his retirement in 1989.

The Christchurch unit had great expertise during the post-war years, with a Dental Department that included David Poswillo (1927–2003), a dental graduate who had joined as an oral and maxillofacial surgeon in 1951. While at the unit, Poswillo commenced research with John Roy into cleft lip and palate. In 1963 he received a Nuffield Scholarship and later the Royal College of Surgeons established a Professorship in Teratology especially for him, enabling him to continue his research in the UK at Down House (Charles Darwin’s former home) and clinical work at East Grinstead. He later became Professor of Craniofacial Surgery in Adelaide, South Australia, and then Professor of Oral Surgery at the Royal Dental Hospital in London.

Other notable surgeons to follow Roy and Milliken at Christchurch included Duncan Simon, Graeme (Blue) Blake, Stewart Sinclair and Sally Langley (present Councillor of RACS). Mark Moore AM, FRACS, who trained in Christchurch, is now the head of the Australian Craniofacial Unit in Adelaide.

Wellington

Frank Hutter (Figure 19) was appointed Senior plastic surgeon at Wellington Hospital in 1947. He moved to the Hutt Hospital in 1952 and established the Wellington Regional Plastic Surgery Service, with outlying clinics in Palmerston North and Hastings. He retired in 1973. In addition to his clinical work, he maintained his links with the military and rose to the rank of brigadier.

During a visit to Barron’s Wessex unit, he met Australian surgeon Anthony (Tony) Emmett and arranged for him to come to Wellington in 1964. After five years in Wellington, Emmett returned to Brisbane, where his clinical work and scholarly publications established him as a great leader in the profession.

When Emmett departed Wellington, Hutter contacted his friend Percy Jayes at East Grinstead, seeking a replacement. As a result, New Zealand-born David Tolhurst returned to his hometown of Wellington. Tolhurst later moved to the Netherlands and became Professor of Plastic Surgery at Leiden University. His research included important early work on fascio-cutaneous flaps and his ‘ATOMIC’ classification of loco-regional flaps has appeared in a number of publications.

Later notable surgeons at Wellington included Max Lovie (who first described the ulnar forearm flap), Colin Calcinai and Gary Duncan.

Auckland

In 1947 the Auckland Hospital Board offered both Percy and Cecily Pickerill full-time positions at the newly opened Middlemore Hospital (Figure 20). They declined the offer but agreed to come to Middlemore once a month to hold weekend clinics and operating sessions. In addition to general anaesthesia, they demonstrated the use of local anaesthetic with procaine and sedation with heroin. They retired from Middlemore in November 1950.

William Manchester (Figure 20) started work at Middlemore Hospital in December 1950, having spent the previous three years in England obtaining his FRCS and working with McIndoe at East Grinstead. Middlemore became the third Plastic Surgery Unit he had created.

He was joined by John Williams (Figure 20) in 1958 and orthodontist John Peat in 1960. Williams became a brilliant surgeon under Manchester at Middlemore, and later gained further experience in the UK. His patience and meticulous technique achieved excellent results across a wide spectrum of cases. Manchester later commented that Williams was the only surgeon he would let operate on him.

John Peat (Figure 20), who had trained in dentistry at the Otago Dental School, had a brilliant career, obtaining two doctorates in orthodontics. He made a huge contribution to the treatment of cleft lip and palate cases, achieving an international reputation for his innovative work and excellent results.

Joan Chapple and Michael Flint were distinguished surgeons who joined the Middlemore unit (Figure 21) in the 1960s. Flint, who had trained with Gillies at Rooksdown House, had a strong background in soft tissue research and the aetiology of Dupuytrens contracture. He also led a large research group in the Auckland School of Medicine. His serendipitous discovery of deforming circles while studying skin biomechanics in the 1970s led to the clinically useful concept of ‘Flint’s Circles’ for selecting optimal skin tension lines in trunk and limb surgery.

Other notable trainees to obtain consultant positions at Middlemore were Earle Brown, Professor Don Liggins, Onkar Mehrotra, John de Geus and Stephen Gilbert in the 1970s.

Manchester secured an international reputation for his work in cleft lip and palate surgery, and also for his work as Secretary General of the International Confederation of Plastic Surgery. He was created Professor of Plastic Surgery in 1975 and given a knighthood by Queen Elizabeth II for his services to plastic surgery in 1987.

Oral surgeons John Hawke and Marsden Bell made valuable contributions to a strong and unified team at the Auckland unit. The senior nurse in charge of plastic surgery patients was Joyce Walters, who served with Manchester in Helwan, Egypt, and at Burwood Hospital in Christchurch. She established a course in plastic surgical nursing.

Waikato Regional Plastic Surgery and Maxillofacial Unit, Hamilton

This unit was founded in the early 1970s by Patrick Beehan and Keith Wilson, both trainees under Sir William Manchester. It was set up on similar lines to the Middlemore unit. Years later, Peter Widdowson and Michael Klaassen were appointed consultants.

Dunedin

For many years, visiting surgeons from Christchurch provided plastic surgery services in Dunedin. Since 2009, a small unit set up by Patrick Lyall and William McMillan has existed within the Department of Surgery at Dunedin Hospital.

Teaching in the regional plastic surgery units

Each regional unit in New Zealand recognises the importance of specialised plastic surgical nursing and continues to hold regular postgraduate courses. Training of plastic surgeons now occurs formally under the auspices of the Royal Australasian College of Surgeons, with selected candidates rotating through approved training programs before taking their final FRACS. Many of these trainees have gained additional specialty training in prominent plastic surgery centres around the world and have benefitted greatly from teaching, clinical work and research within internationally recognised units. Many have since progressed to consultant posts in New Zealand, Australia or other parts of the world.

Trainees from other countries have been a constant part of plastic surgery practice in New Zealand, coming from many countries including Australia, Japan, Thailand, India, China, USA and the UK. They have given New Zealand surgeons a wider perspective of the scope of plastic surgery throughout the world.

Recent and current plastic surgery research in New Zealand

Julian Lofts

As a plastic surgery registrar in the early 1990s working with Dr Nicholas Birchall at the Department of Molecular Medicine at the Auckland Medical School, Julian Lofts established the National Cryopreserved Cadaveric Skin Bank, and was the first to use autologous and allogeneic cultured keratinocytes in the treatment of burns and chronic leg ulcers. His work led to the establishment of regional burns units and eventually, the National Burns Centre (together forming the National Burn Service).

Swee Tan

Swee Tan founded the Gillies McIndoe Research Institute (GMRI) in Wellington in 2013. Dr Tan has led a wide range of clinical and basic science research subjects, including vascular anomalies, fibrotic conditions, craniomaxillofacial surgery, head and neck cancer surgery, facial palsy and microsurgery.

The GMRI team discovered stem cells as being the origin of infantile haemangioma (IH) and demonstrated that these stem cells are regulated by the renin-angiotensin system. Since 2014 his team has applied their approach to IH in their investigation and treatment of cancer.

Michelle Locke

Michelle Locke, a plastic surgery registrar from 2005 to 2010, worked with the University of Auckland during her advanced training. She visited the Bernard O’Brien Institute of Microsurgery in Melbourne, Australia, to study new techniques in adipose stem cell isolation, and established a stem cell research group at the School of Biological Sciences, Auckland University. Over the years, the Manchester Trust has generously supported her ongoing research into full thickness skin engineering and the treatment of keloid scar tissue.

Conclusion

The New Zealand regional plastic surgery units set up after WWII were initially based on the Gillies-McIndoe-Mowlem model that included a dental department with orthodontists, oral surgeons, prosthodontists and dental technicians. With the passage of time, local changes to each unit have been made to accommodate developments in the specialty.

The surgeons who initially developed these units all had a military background and had a reputation for military discipline.

From small beginnings, plastic and reconstructive surgery units have developed into significant surgical departments in each region. In addition to the regional units, there are now practising plastic surgeons in most cities across the country, and visiting surgeons provide a valuable service in the smaller centres.

Perfection in plastic surgery is only just good enough.

—Sir William Manchester

Acknowledgements

The authors have been researching the history of New Zealand’s contribution to plastic surgery for many years and are grateful for the support and contributions of many friends and colleagues. We sincerely apologise if we have overlooked any contributor. Our special thanks go to: Harvey Brown, the Gillies family and Margaret Divers, Andrew Bamji, Murray Meikle, Stewart Sinclair, Lesley Simon, Gary Duncan, Swee Tan, Julian Lofts, Judith Shea and the trustees of the Manchester Charitable Trust, Margaret Fraser, Ian Holten, Mollie Locke (née Lentaigne), Bob Marchant, Brent Tanner, Darryl Tong, John Peat and John Williams. Also, the Royal College of Surgeons (Eng) archives, Royal Australasian College of Surgeons archives, New Zealand Defence Force archives, Hocken Library, University of Otago and the NZ Medical Journal archives.

Many of the images are added from Michael F Klaassen’s personal collection.

Disclosure

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Revised: December 4, 2017 AEST

.png)

.png)

.png)

_with_his_staff_at_the_plastic_surgery_unit__burwood_hospi.jpeg)

.png)

.png)

.png)

_with_his_staff_at_the_plastic_surgery_unit__burwood_hospi.jpeg)