Introduction

FlexHD® acellular dermal matrix (ADM) is a tissue matrix derived from human dermis that has been processed to remove cellular components that may trigger an immune or inflammatory response.1,2 It is one of many types of ADM present on the market, others being derived from porcine dermis or bovine tissue.2 First described as tissue replacement for burns victims in 1995 by Wainwright,3 the use of ADMs has expanded rapidly to areas of surgery including thoracic, abdominal wall and pelvic reconstruction, head, neck and breast reconstruction.

Despite widespread use of ADMs, with the 2016 Plastic Surgery Statistic Report quoting 53 per cent4 of all reported plastic reconstructive breast procedures in the United States incorporating ADM use, a recent systematic review by Blazeby and colleagues5 was unable to find high quality evidence to demonstrate its impact on outcomes in immediate breast reconstruction, quoting lack of robust study designs and long-term follow up. Complication rates associated with FlexHD® are reported at 16.5 per cent, similar to AlloDerm,6 which includes soft tissue infection, flap necrosis, seroma and implant exposure.

Within the last five years, a new phenomenon termed ‘red breast syndrome’ (RBS) has emerged. It is poorly understood but is associated with the use of ADM in breast reconstruction, presenting as cutaneous erythema over the breast without systemic signs of infection. We present a case of RBS in a patient who had FlexHD® inserted, presenting with cutaneous erythema, but with associated blistering, and review the current literature on this phenomenon.

Case report

A 43-year-old woman presented with a self-detected right breast lump. The patient had previously had knee surgery, is a non-smoker, and has given birth to two children. She works as a physical education teacher and is otherwise fit and healthy.

Core biopsies of right breast tissue prior to surgery confirmed grade I invasive ductal carcinoma, oestrogen and progesterone receptor positive and HER2 negative. The patient underwent a skin sparing right mastectomy, right axillary node dissection and tissue expander (TE) insertion with FlexHD®. A submuscular approach to TE insertion was performed underneath pectoralis major and serratus fascia with a 6 cm x 16 cm sheet of pliable FlexHD® used to cover the exposed lower pole of the TE, sutured on the superior aspect to pectoralis major and inferiorly to the level of inframammary fold using Vicryl, with two drain tubes inserted. The patient was administered perioperative cefazolin antibiotic which continued during her admission. The drain tubes were removed on the third postoperative day, and the patient was discharged home with cephalexin.

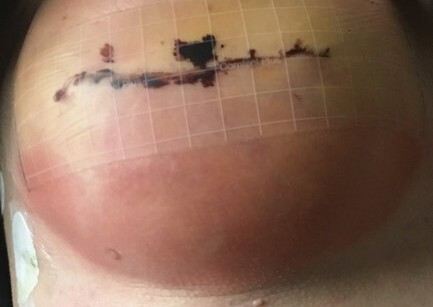

On day seven post operation, the patient noted warmth, erythema (Figure 1), swelling and itchiness around the lower pole of her right breast, specifically in the skin directly overlying the ADM, and was readmitted.

The patient’s temperature was 37.4 C, with a white cell count of 11.5 x 109 cells/L (normal range 4.0– 1.0) and CRP of 45 mg/L (normal range < 5). She commenced on IV Flucloxacillin for presumed infection. On the third day of admission, blistering was noted at the inferior pole of the right breast directly overlying and in the shape of the inserted FlexHD® ADM (Figure 2).

An ultrasound scan of the breast was performed, with no collection or abscess present, with a very small amount of fluid surrounding the TE. A swab of the blister showed presence of white cells, but no organisms were cultured. Antibiotics were changed to Tazocin and intravenous hydrocortisone began. On the subsequent day she was taken to theatre for washout and removal of the ADM with preservation of the TE due to increased blistering with skin integrity in question, despite the patient being on Tazocin and hydrocortisone. Intraoperative findings were turbid fluid but no pus around the TE. Tissue, swabs of fluid and the FlexHD® (Figure 3) were sent off for histopathology, microscopy and culture. The sub-pectoral pocket was washed out with sterile saline, with 50cc of fluid removed from the TE.

Hydrocortisone ceased on the first postoperative day, and vancomycin commenced in conjunction with Tazocin. Within twenty-four hours, the area showed improvement with significantly less redness noted, and her antibiotics were changed to oral Flucloxacillin on the fifth postoperative day. She was discharged home on the seventh postoperative day with four weeks of Flucloxacillin to cover the possibility of infection. Cultures of right breast fluid, blister fluid, capsule and surrounding breast tissue were negative, with occasional leukocytes seen on microscopy. Histopathology of ADM demonstrated strips of dense fibroadipose tissue with neutrophilic infiltrate, with irregular cystic spaces present and with no granulomas identified (Figure 4), suggestive of abscess formation reaction against foreign material. On her one-month review, the patient’s symptoms had completely resolved. The patient has since undergone a TE to implant exchange on the right breast, with implant inserted on the contralateral side (Figure 5).

Discussion

Since the first documented use of ADM for breast reconstruction in the scientific literature by Breuing and Warren7 in 2005, the use of ADMs in immediate breast reconstruction has increased significantly, with a recent survey quoting 84 per cent of plastic surgeon respondents routinely using ADM in breast reconstruction8 and multiple authors reporting favourable outcomes.6 ADM is sutured between the lower border of pectoralis muscle and chest wall, creating a lower-pole sling where a defect would normally exist. This theoretically allows both for greater intraoperative filling of TE and reduced time until expansion is complete, and, in some cases where appropriate, a single-stage procedure due to the reinforced subpectoral pocket allowing for immediate insertion of implant.5

‘Red breast syndrome’ was first documented in 20099 after the authors of a study into AlloDerm ADM noted some patients developed a non-infectious erythema that mimicked cellulitis present at the lower mastectomy skin flap overlying the ADM without local signs of infection. In these cases, the erythema noted was refractory to antibiotic therapy and self-limiting, hypothesised to be an inflammatory response to the preservatives in which AlloDerm was packaged.9 Newman and colleagues10 noted similar findings in relation to AlloDerm, reporting there was no pain, elevated skin temperature or induration present. However, the authors reported that there was no elevations of serum markers such as white blood cell count and C-reactive protein, contrary to our findings, and that if left untreated, was self-limiting and self-resolving. Since this first documentation in the literature of an erythematous reaction, further cases have been reported, although variable in terms of period of onset after ADM insertion, associated symptoms and treatment methodologies.

Presentation

Multiple case reports and series9,11–13 have identified RBS as characterized by a cutaneous erythema localized to skin overlying an ADM, with some reports14 quoting an incidence of up to 7.6 per cent. Most studies so far have mentioned RBS in passing, without clear case presentation and analysis. Slavin and colleagues11 reported a case series of four patients who had an ADM inserted presenting with breast erythema resistant to antibiotics; some presenting with symptoms of erythema, and systemic symptoms of fevers, chills and night sweats associated with breast erythema that manifested up to nine months after the initial operation. Kim and colleagues6 also noted similar clinical findings, further reporting an absence of objective signs of infection such as fever and leukocytosis, and no radiographic evidence of seroma or abscess. Their findings contrast with our own, which found leukocytosis along with the development of an aseptic abscess from foreign body reaction, and hence the presence or absence of leukocytosis and radiologic findings should not necessarily preclude a diagnosis of RBS.

In recent literature, and from our case presented, there is emerging evidence of heterogeneity in RBS presentations beyond just cutaneous erythema. A report by Saunders and colleagues12 found pustular dermatitis overlying erythema present on the lower pole of the breast that had FlexHD® inserted and which failed to respond to antibiotic therapy.

Aetiology

Multiple theories as to why RBS develops have been put forward. Kim and colleagues15 reported a case of incorrect ADM insertion leading to an erythematous cutaneous breast that required removal of the ADM; ADM exhibits polarity, and must be inserted with the fenestrated (dermal) surface opposing soft tissue and the smooth surface facing the TE or implant. The authors postulate the possibility of the incorporation of the graft being compromised by incorrect insertion leading to lack of proper tissue ingrowth and revascularization, in turn leading to the host immune system identifying the ADM as foreign and subsequently the development of a foreign body reaction.

The possibility of incorrect preparation of ADM was also explored, with Kim and colleagues13 reporting sterile AlloDerm preparation being associated with a clinically, but not statistically, decreased incidence of seroma, necrosis and RBS compared to aseptic ADM preparation. Those with presumed RBS were treated empirically for possible cellulitis, with the erythema resolving over several weeks in all patients.

An earlier review by Jacobson and colleagues16 noted unilateral RBS in some of the authors’ patients who underwent bilateral reconstruction with ADM. The reason for this peculiarity is uncertain, as preparation of the ADM and its insertion should be very similar, if not identical, as performed by the same surgeon for the same patient. Unless the chemical constituents of the ADM used were highly variable between the same product, which seems unlikely, the more plausible explanation is that the current methods of manufacture of ADM does not eliminate all cellular antigenic products, which some manufacturers have alluded to.2

All cases of RBS share the common phenomenon of symptoms presenting from a week to months after initial ADM insertion. The delayed presentation of documented cases of RBS, and cell infiltrate found in the biopsy, combined with resolution from using corticosteroids—a known immunosuppressive agent—suggests a likely immunological component, as reported by Slavin and colleagues11 in a four-case series where immune-suppressant medication resolved the symptoms. The delayed presentation of RBS suggests a type IV T cell-mediated hypersensitivity reaction, similar to diseases including type I diabetes and multiple sclerosis, brought on by activated T cell lymphocytes.17 However, this reaction usually occurs due to prior sensitisation to a specific antigen, possibly due to inadequate preparation of the ADM or inadvertent impregnation of antigens into the ADM in theatre during preparations for insertion. In this case, the histopathology report noted a sterile foreign body reaction consistent with the hypothesis of delayed hypersensitivity.

Similar cutaneous erythematous events have occurred during breast reconstructions without the use of ADM, which some have attributed to lymphatic obstruction,18 while others19 have documented as a ‘delayed breast cellulitis’ mimicking symptoms of RBS. Delayed breast cellulitis, occurring on dependent breast portions around and below the nipple and areola region and reported as being resistant to antibiotics, improved after the patient changed to a supine position, and was self-resolving. It is possible that RBS is delayed breast cellulitis that is now being noticed in patients with ADM inserted, however with the current, minimal number of histopathological studies available on either phenomenon, such a distinction cannot be made.

Treatment

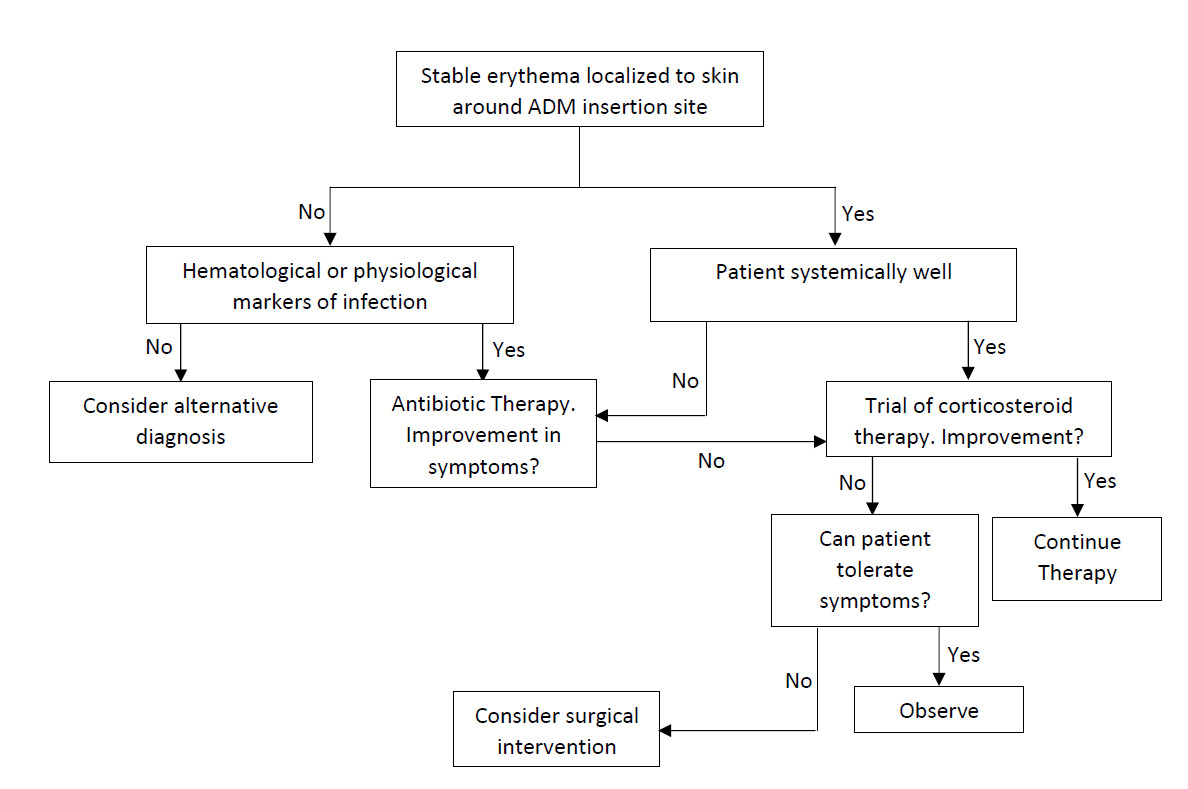

Due to the lack of reporting and understanding of RBS, there is currently no recognised treatment regime. The heterogeneous presentations of RBS also suggest that it is likely a condition with multiple causes but which present in a similar manner, making it difficult to distinguish from one case to another and to treat appropriately. However, the presentations of erythema can be associated with severe outcomes depending on cause, and hence RBS should be a diagnosis of exclusion, once other diagnosis have been ruled out.

If there are clear signs of cellulitis, including spreading cutaneous erythema associated with fever and leukocytosis, the patient should be treated for cellulitis as per empiric antibiotic therapy, with swabs of fluid for culture and sensitivities. Whether worsening cellulitis requires the removal of the ADM, despite antibiotic therapy, is dependent on the judgement of a surgeon.

Should antibiotic therapy fail, and the erythema is noted to be stable with the patient systemically well, a trial of corticosteroids may be considered. Commencing steroid therapy prior to antibiotic therapy is discouraged, as it transiently increases the white cell count—due to inhibition of white cell adhesion to endothelial cells for migration into tissue—hence reducing the immunological response.17

The question of ADM removal in RBS is patient and surgeon dependent. Severe reactions or multiple episodes of RBS should warrant strong consideration of removal.

Figure 6 outlines a treatment algorithm when presented with cutaneous erythema after insertion of AD.

Conclusion

The aetiology, risk factors and treatment of RBS red breast syndrome are elusive. While the presentations of RBS can be varied, the current literature, as well as our case, demonstrate that RBS is primarily characterised by a cutaneous erythema over the region of an inserted ADM. The presence or absence of systemic symptoms should not be the primary determining factor in stratifying RBS from infection, but rather the presence or absence of stable erythema. Further recognition and study of this condition is required to determine cause and appropriate treatment.

Patient consent

Patients signed informed consent regarding publishing their data and photographs.

Disclosure

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Revised: August 24, 2017; October 5, 2017