Introduction

Breast hypertrophy is for some women a cause of considerable physical and psychosocial impairment, and adversely affects quality of life. Physical symptoms may include: chronic back, neck, shoulder and breast pain; skin rashes; headaches; shoulder grooving from the constant pressure of bra straps; a reduced capacity for carrying out daily activities and exercise; and numbness or tingling in hands/fingers.1 Psychosocially, women with breast hypertrophy often display low self-esteem and poor body image, reduced psychosexual function, anxiety and depression.2

Breast reduction surgery is widely known to be the most effective treatment for breast hypertrophy.3 Surgery provides almost immediate symptomatic relief in most cases, and considerably improves the health-related quality of life and wellbeing in women suffering from the functional symptoms of breast hypertrophy.4,5 Despite these proven benefits, an increase in the prevalence of breast hypertrophy, and hence in demand for breast reductions, has led to restrictions being placed on surgery by healthcare funders and third-party providers in many jurisdictions. Arbitrary restrictions on either the minimum amount of breast tissue required to be removed at surgery or a body mass index cut-off point have been introduced in many institutions and countries worldwide.6

Measurement of breast volume plays an important role in breast reduction, reconstruction, developmental asymmetry and augmentation. In women with breast hypertrophy it is important for preoperative planning, in intraoperative decision-making regarding the amount of tissue to be taken from each breast to achieve symmetry, and where removal of a minimum amount of breast tissue is required to justify surgery.7–11 Accurate estimation of breast volume and predicted tissue resection weight also promotes improved counsel to the patient and provides a valuable guide to training surgeons.

A variety of techniques are described in the literature to meet the need for accurate and objective measurement of breast volumes in the clinical setting including magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), mammography, plaster casting, Grossman-Roudner plastic cups, water displacement, anthropometric measurement and 3D surface imaging.12–21

In a situation where a woman is undergoing post-mastectomy breast reconstruction, the gold standard for measuring the breast tissue volume for reconstruction is the Archimedes method of water displacement of the mastectomy specimen.22 When measuring breast tissue volume in the intact state, such as in candidates for breast reduction surgery, MRI is reported as being the most accurate.23 However, MRI is expensive and not always accessible. Three-dimensional laser scanning has also been demonstrated as a valid method of breast volume measurement,16,17,22 but some centres lack access to this technology. Water displacement of the intact breast has been used in some centres since 1970, but has not previously been validated against more recent methods.24

The purpose of this study is to assess the validity of measuring breast tissue volume using water displacement of the intact breast and to compare this measurement technique with 3D laser scan measurement.

Methods

Patient selection and measurement

A prospective cohort study was performed at Flinders Medical Centre in Adelaide, Australia. All women aged 18 years and above with breast hypertrophy who were eligible to be placed on a waiting list for bilateral breast reduction surgery between March 2007 and February 2016 were informed of the study. Women who met the eligibility criteria were invited to voluntarily participate in the study and were provided with a letter and information sheet further outlining the study. Women who were unable to complete written questionnaires, had impaired cognitive capacity, or refused to participate, were excluded from the study. Approval was obtained for this study from the local Southern Adelaide Clinical Human Research Ethics Committee (SAC HREC approval 118.056).

Bilateral breast volumes were obtained preoperatively and/or at 12 months postoperatively by two different techniques—3D laser scanning and water displacement. Patients proceeded immediately from measurement by water displacement to the 3D scanning within the same appointment to allow direct comparison. Some participants had breast volume measurements taken at both the preoperative and 12 months postoperative times, while other participants were measured once as additional measurement was considered onerous for some patients.

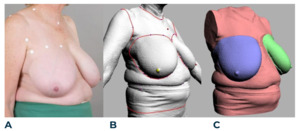

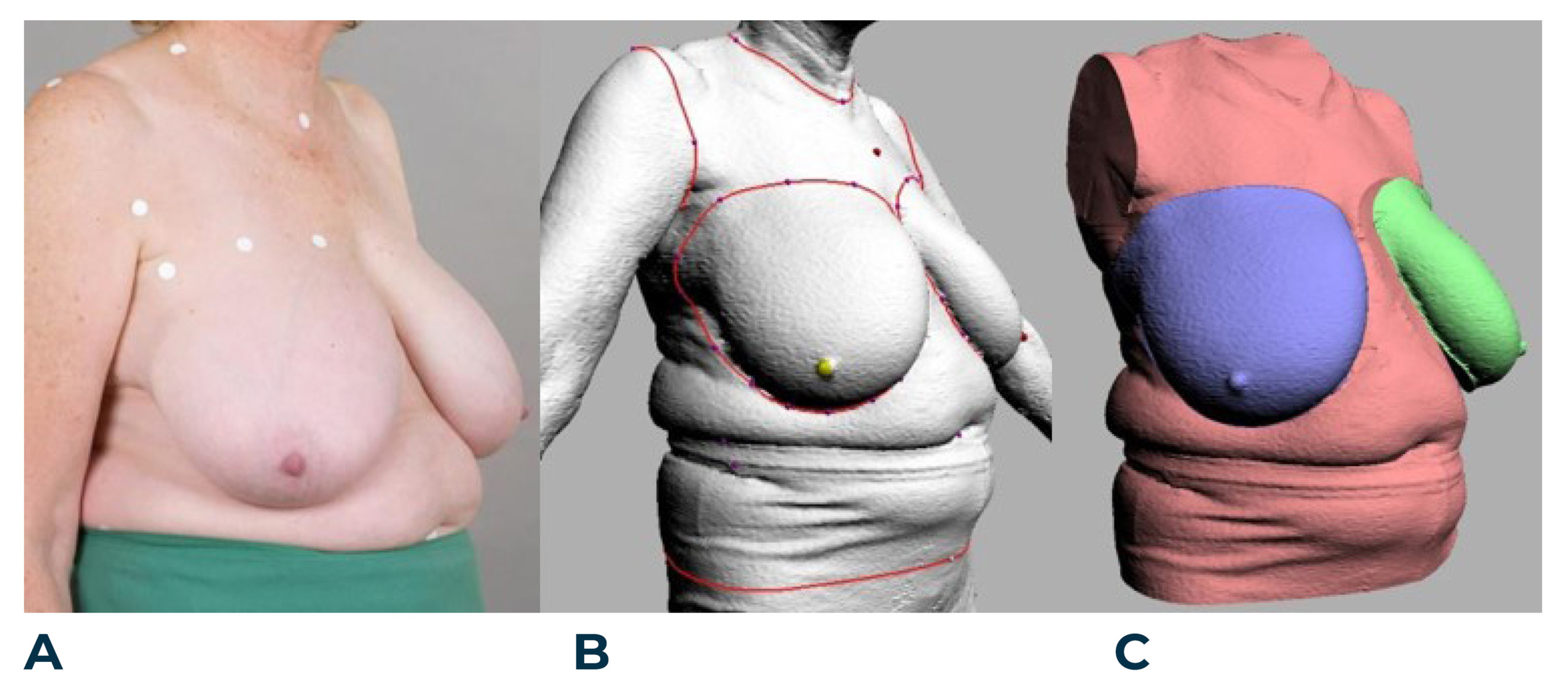

Three-dimensional laser body scanning was performed using a Cyberware WBX scanner (Cyberware, Monterey, USA) and Cyslice software (Headus Pty Ltd, Perth, Australia). The Cyberware WBX scanner has four sets of laser heads and cameras that move vertically to scan the surface anatomy of subjects in the upright position. Prior to scanning, the assessor placed ‘landmarks’ on subjects using palpation to demarcate selected anatomical areas and the breast perimeter. Breast volume was measured according to the validated protocol described by Veitch and colleagues25 and Yip and colleagues.22 Figure 1 illustrates the application of landmarks on a large-breasted woman to section the breast from the torso for volume analysis.

Water displacement measurements based on Archimedes’ principle was performed on each breast to determine the volume, as described by Schultz and colleagues.12 A large calibrated container was filled with warm water and the patient asked to individually immerse each breast into the container, using a specially modified surgical bed and ensuring that the superior and lateral edges of the breast were at water level (Figure 2). Individual breast volumes were then determined by the amount of water displaced.

Statistical analysis

Data was entered into a spreadsheet and statistical analysis performed using SPSS v23.0 statistical software (IBM Corp, Armonk, New York). Pearson coefficients were calculated to assess the linear association between the two measurement techniques.

The strength of any correlation between the two techniques was then determined with a Bland-Altman analysis.26 This analysis plots the mean breast volume measurements for both techniques against their differences. If the two methods are comparable and in agreement, then the differences should be small and the mean of the differences should be close to zero. The limits of agreement (95%) were formed using the mean difference in volumes ±1.96 standard deviation (SD) of the differences in volumes. Linear regression analysis was performed to assess proportional bias between the two measurement techniques.

Results

A total of 322 breasts were measured in the study using both 3D laser scanner and water displacement techniques—194 breasts (97 women) were measured preoperatively and 128 breasts (64 women) were measured postoperatively. The mean breast volume according to 3D laser scan was 1440 ml (SD = 588 ml) and using water displacement was 1419 ml (SD = 811 ml).

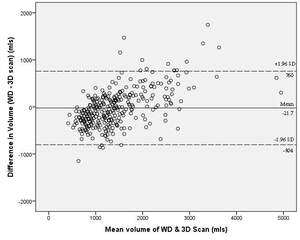

In comparing the breast volumes obtained from 3D laser scanning and water displacement, a Pearson correlation demonstrated a strong positive linear association between the two methods (r = 0.89, p <0.001) (Figure 3).

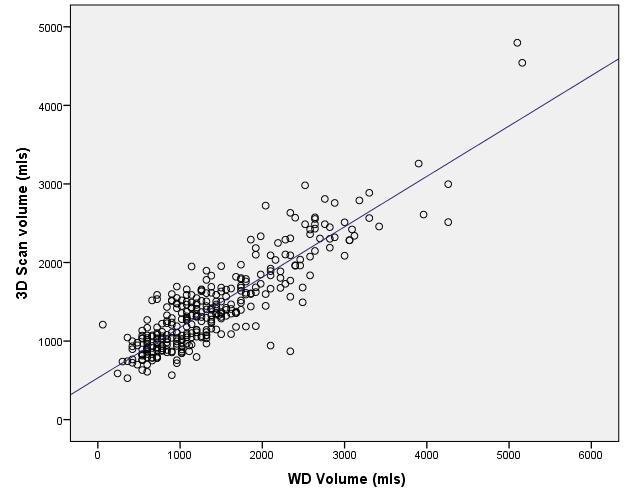

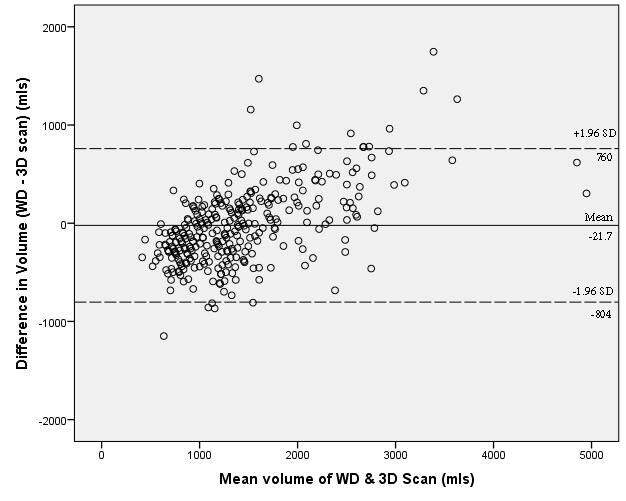

Figure 4 shows the results of the Bland-Altman plot showing the differences between the two techniques plotted against the averages of the two techniques. A mean difference of −21.7 ml with a standard deviation of 399 ml was found between the two techniques. While most values were within the 95 percent limits of agreement (a lower limit of −804 ml and an upper limit of 760 ml), the majority of the data points are widely spread across this range and do not lie close to zero, which would have been the case if there was good agreement between the measured values.

Linear regression analysis confirmed a degree of proportional bias, meaning that one method gave values that were consistently higher or lower than those of the other method. In this instance, the breast volumes obtained from water displacement tended to be larger than those from the 3D scanner, and the difference between the two methods increased as the mean volume increased. This is evident from the plot where there was a discernable trend for more points to be above the line of mean difference in volume as the mean volume increased (Figure 4).

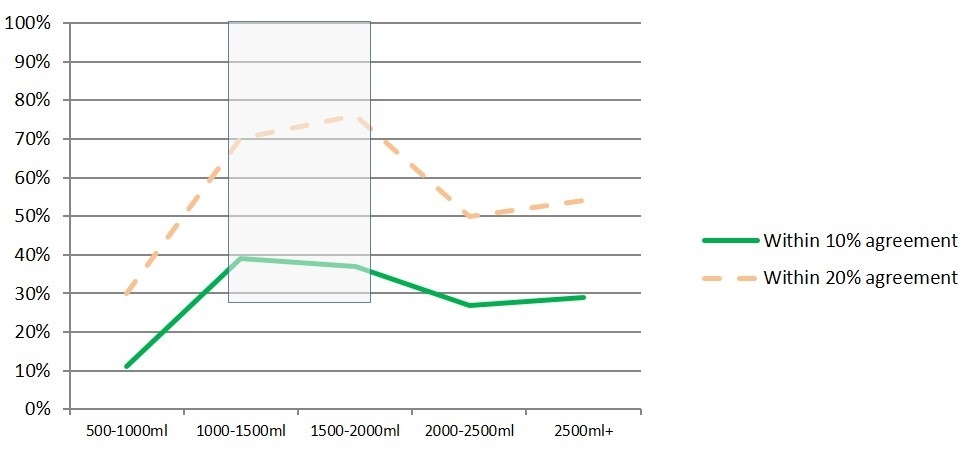

The statistical analyses therefore suggest that despite a strong linear correlation between the two methods of breast volume measurement, the measures have low agreement on actual values. The water displacement values were consistently larger than the 3D scan values. The greatest agreement in breast volume measurement between the two methods (within 10 percent) was seen for volumes between 1000 and 2000 ml (Figure 5). The findings of this study are in contrast to previous studies conducted in our unit that demonstrated equivalence between 3D laser scanner and direct water displacement of mastectomy specimens, and also between the 3D laser scanner and MRI.

Figure 6 demonstrates the breast volumes measured using water displacement and 3D laser scanning in a single patient both preoperatively and postoperatively at 12 months. The amount of breast tissue removed from each breast was 1444 gm, totalling 2888 gm. The patient’s body weight remained relatively stable during this period—127 kg prior to surgery and 125.3 kg at the postoperative time point.

Discussion

A large number of techniques for the objective measurement of breast volume have been described in the literature. However, these techniques often vary in accuracy and reliability and some are limited in their application to large-breasted patients. Many studies specifically on women with breast hypertrophy aim to develop a formula for estimating breast reduction weight in reduction mammoplasty rather than the assessment of breast volumes both before and after surgery.27–32 This is most likely driven by restrictions placed on breast reduction surgery by healthcare providers or insurance companies which often require surgeons to predict a minimum weight of resected breast tissue. Although a formula to predict tissue resection weight is clinically useful, there remains a need for the accurate determination of absolute breast volumes both in planning breast surgery and in assessing outcomes following surgery.

The use of 3D scanning in the specialty of plastic and reconstructive surgery has increased in recent times. It provides a valuable and non-invasive assessment of the breast for the surgeon, describing the volume, shape, contour, projection and symmetry. This information can not only be useful in the preoperative phase but in the assessment of postoperative outcomes and symmetry. The accurate and objective measurement of breast volume is particularly important in the complex field of breast reconstruction, such as in assessing outcomes following autologous fat grafting techniques16 and preoperatively for unilateral reduction or augmentation for asymmetry.33,34 Three-dimensional scanning technology has also been employed in other areas of plastic surgery including facial symmetrisation35,36 and for the preoperative planning of nasal surgery.37

The Cyberware WBX laser scanner and CySlice software used in this study have previously been validated against water displacement in measuring mastectomy specimens with a strong correlation demonstrated.22 The same 3D laser scanner and protocol were also found to be strongly equivalent to non-contrast MRI for the assessment of breast volume.16

The most accurate metric of true breast tissue volume is water displacement of mastectomy specimens, however, this is not applicable other than in post-mastectomy reconstruction scenarios.20,22,38 Additionally, volume measurement of the intact breast has proven to be more variable due to the challenge of correctly differentiating breast tissue from the chest wall.

This study aimed to determine whether water displacement is a valid lower-cost method of breast volume measurement in women with breast hypertrophy compared to 3D laser scanning. Our measurement of 322 breasts by both 3D laser scan and water displacement showed a close association between the two techniques but the water displacement method had a clear tendency to estimate a larger volume than the 3D scan. A possible explanation for the difference between techniques is that measurement using water displacement requires the patient to be in a prone position, which may change the form of the breast and add axillary or abdominal fat to the breast measurement. In contrast, patients are in the upright position for measurement with the 3D scanner.

The water displacement technique is also highly dependent on the positioning of the patient. Alternative devices for the water displacement technique have been described to address the disadvantages of the immersion technique used in this study.39 Our study supports previous findings that, although water displacement is easily accessible and a low-cost option, the technique has relatively low accuracy for measurement of the intact breast due to poor reproducibility.18,40 Three-dimensional scanning and MRI display the highest level of accuracy and reliability and provide a comprehensive assessment of volume and shape for breasts in situ. However, these techniques can be cost-prohibitive. Linear anthropometric measurements are less accurate, however, the costs are negligible, they are fast and they have been shown to provide a reliable estimate of breast volume in the clinical setting.14,15,19,41

Another source of difference is that 3D scanning technology allows for a curved cut plane at the back of the breast where it can digitally follow the curved chest wall, while water displacement has by definition a flat cut plane at the water level. The manual positioning of landmarks prior to 3D scanning using palpation to accurately identify the margins of the breast base, and relying on these points later in the scan image, helps to control for potential location error.

Key advantages of this study are its large sample size and that the data was collected prospectively. One limitation of this study is that not all participants had breast volume measurements taken at both the preoperative and 12 months postoperative times. It was decided that additional measurement was too onerous for some patients given the commitments associated with voluntarily participating in the study. As a result, both of these techniques were performed on discrete subsets of patients at each time point.

Future extensions to this work would be to incorporate the results of comprehensive anthropometric body shape assessment that was also conducted pre- and postoperatively as part of this study. Analysis of patient-reported outcome measures data collected during the study would also further enhance our understanding of surgery outcomes and of the overall satisfaction in women with reduction in breast volume through surgery.

Conclusion

This study found a strong linear association between the measurement of breast volumes using water displacement and 3D laser scanning techniques in women with breast hypertrophy but the methods have low agreement on actual values. While water displacement may be more convenient and accessible in clinical practice, 3D scanning remains preferable as it has been proven to be a more accurate and reliable technique for the determination of intact breast volume.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge and thank the following people: members of the AFESA research group; Andrea Smallman, nurse practitioner; David Summerhayes and Lynton Emerson for clinical photography; Chris Leigh for the water displacement apparatus; Phil Dench from Headus Australia for the design and volume calculation software; Kathleen Robinette for assistance in scanner selection; Professor David Watson and Professor Julie Ratcliffe for PhD supervision; the Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship for providing a PhD scholarship at Flinders University.

Consent to publish

Patients signed informed consent regarding publishing their data and photographs.

Disclosure

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Revised: February 12, 2018 AEST