Introduction

A recent study1 of the New Zealand plastic and reconstructive surgery (PRS) workforce identified that there is currently a ratio of one plastic surgeon for every 69,000 people living in New Zealand. This is lower than the ideal ratio of one for every 60,000 people. In addition to identifying that nationally the quantity of plastic surgeons is low, the authors also identified that there was marked regional variation with regional ratios varying between 1:188,000 and 1:51,000. As a whole, New Zealand’s medical workforce has an unbalanced geographical distribution with 80 per cent of doctors practising in urban areas.2

This difference is likely to result in inequity of access to, and outcomes from, specialist PRS services for those living outside the main cities. Ministry of Health New Zealand data reports one in four New Zealanders live in rural areas or small towns.3 Māori represent a higher proportion of the population living in small urban or rural areas.4 Patients often have to travel hundreds of kilometres for specialist plastic surgery treatment. The services offered in different centres are not standardised resulting in a ‘postcode lottery’ for patients.5

Health New Zealand have made a commitment to reducing health inequities within the country. Increasing plastic surgeon numbers in regional centres is likely to be part of the solution to improve equity of access. Growing a regional service may come from migration of current specialists or new specialists starting practice in regional centres. Currently, no data exist for future workforce intentions of PRS trainees.

Presently, the distribution of the PRS workforce is clustered around four tertiary hospitals located in large metropolitan areas (Auckland, Wellington/Hutt, Hamilton and Christchurch). These large metropolitan areas, which also house regional and national burns units, have populations exceeding 160,000.6 There are also three smaller metropolitan or regional areas (Whangārei, Tauranga and Dunedin), which provide secondary plastic surgery services, but do not provide tertiary services including cleft or craniofacial surgery and do not have a regional burn unit.

The aim of this study is to identify where PRS trainees plan on working after completion of training and fellowship and whether they would like to work publicly or privately or a combination of both. In addition, we explored what the perceived barriers or benefits are to working as a plastic surgeon in a regional centre. The survey aimed to assess various demographic characteristics, work preferences, financial considerations and personal factors impacting trainees’ career decisions.

Methods

An anonymous online questionnaire (see Supplementary material 1) was sent to PRS trainees as at August 2022 (Surgical Education and Training, SET 1–5), those starting training in 2023 and those who obtained their FRACS (Fellow of the Royal Australasian College of Surgeons, Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery) in the preceding two years. Data was collated and analysed using Microsoft Excel (version 16.86, Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, Washington, USA). All data was anonymous. The questionnaire encompassed questions related to demographic information, rural background, previous experience in regional centres, family responsibilities, preferred work locations, aspirations for private practice, desired work–life balance, and factors influencing career choices. Research was carried out in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

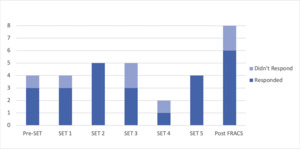

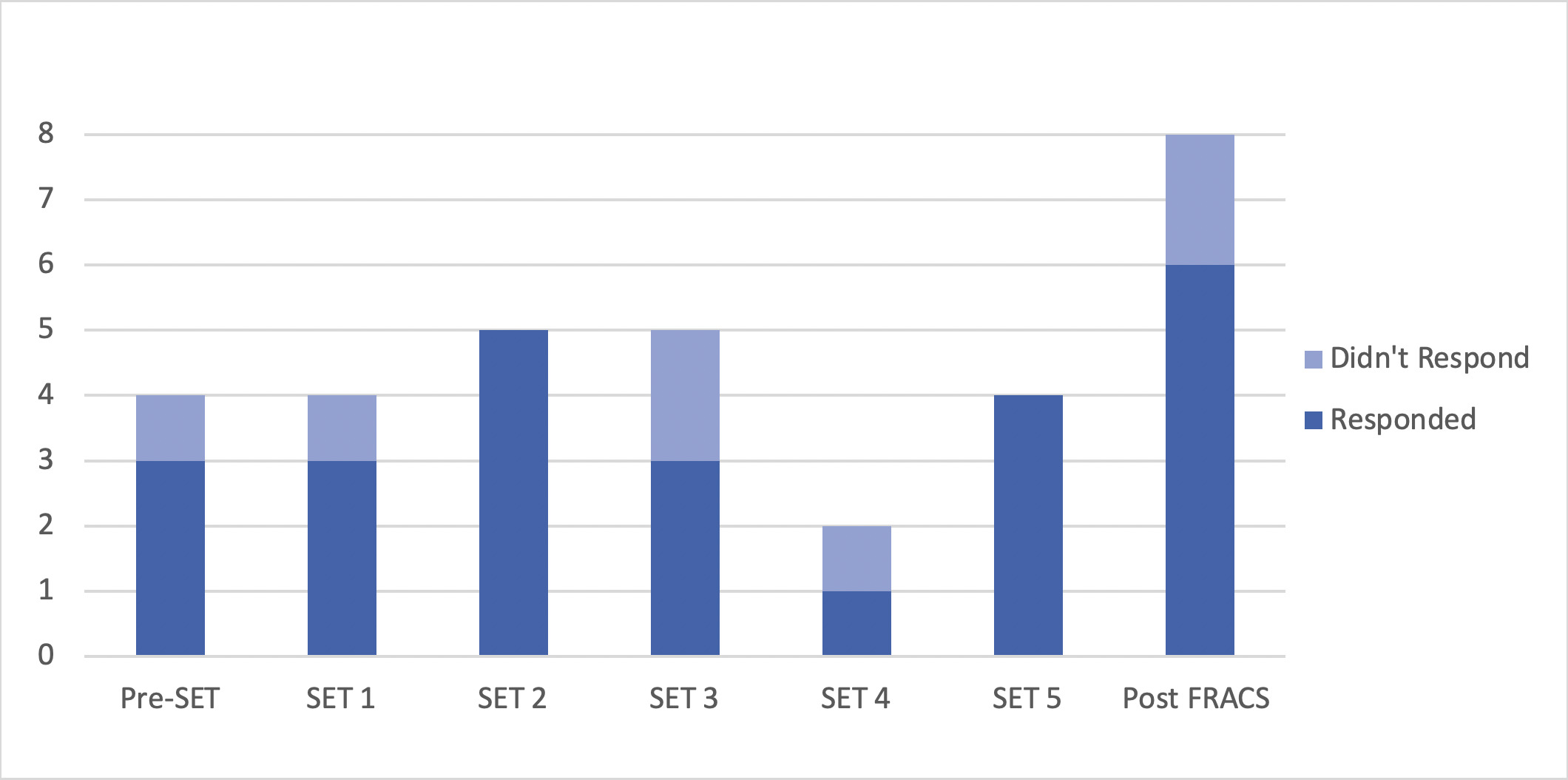

A total of 31 trainees were sent the questionnaire, of whom 25 provided complete responses resulting in a response rate of 81 per cent. Response rates from each year group ranged from 50 per cent for SET 4 to 100 per cent for SETS 2 and 5 (Figure 1). An equal number of females and males responded, which is reflective of the gender equity in our cohort.

A total of 8 per cent of respondents identified themselves as having a rural background, while an additional 35 per cent partially identified as such. Over 50 per cent of respondents had prior experience working in smaller regional centres as medical students or junior doctors.

Following completion of their training, most respondents (84%) expressed a preference for working in Auckland, Hamilton, Lower Hutt (Wellington) or Christchurch hospitals. Notably, only one person out of the 25 respondents indicated they would like to work in a regional centre as a plastic surgeon immediately after qualifying. They did not identify as being from a rural background. Of the four respondents (16%) who indicated that after five years as a plastic surgeon they would prefer to be working in a regional centre, three identified as being from a rural background.

The survey revealed that 58 per cent of respondents have dependent children, underscoring the importance of fostering family-friendly work environments. Additionally, 26 per cent of respondents reported providing financial support to a partner.

If they were to work regionally, the regional centres respondents found most attractive to live and work in included Queenstown/Wānaka, Hawkes Bay, Nelson and Whangārei (Figure 2).

Respondents were surveyed on their future intentions for private practice. Thirty-five percent aspired to work in private practice within a year of becoming a plastic surgeon (Figure 3). The majority of respondents (96%) expressed a long-term desire to work in private practice, envisioning an average 60/40 split between public and private work after five years of practice.

Three-quarters (75%) of respondents emphasised the significance of having another plastic surgeon in the same centre. Factors such as the ability to take leave, after-hours call arrangements, and the availability of a private operating facility were considered ‘essential’ by the trainees. Ninety-two percent of respondents rated it as ‘very important’ or ‘essential’ to have formal audit and continuing professional development (CPD) with connection to a tertiary unit and 76 per cent would want a formal mentor. The ability to be able to perform subspecialist procedures was ‘very important’ to over half of respondents (Table 1).

Financial considerations, particularly the availability of publicly-funded consultant positions and regional housing prices, also emerged as important factors. Furthermore, 85 per cent of respondents identified good quality schooling or child care as essential, with over 50 per cent requiring employment opportunities for their partners. One respondent commented that it wasn’t possible for their partner to work in a regional centre due to their job and this was a limiting factor.

Working within a collaborative team, having opportunities for teaching and growth within the department, and creating affiliations with established specialties were highlighted as important considerations. Many felt it would be important to work with registrars, have scope for the department to grow and be able to teach. Concerns were raised regarding limited utilisation of skills learned in complex cases, particularly with head and neck procedures.

Discussion

This is the first reported analysis of the future work intentions of New Zealand PRS trainees. It identifies perceived barriers to working in regional centres and personal factors which influence the career decisions of PRS trainees. This information can inform strategic workforce planning for the distribution of plastic surgeons in New Zealand.

It has been well established that exposure to regional experiences prior to entering and during medical school positively influence choices to return to work in regional centres.7 Being from a rural background has been identified as an important predictor of rural intentions and rural employment.8 Consideration could be made to preferentially select future trainees from a rural background. Currently, several established centres engage in outreach clinics or perform surgeries in smaller hospitals, such as the Hutt Hospital surgeons’ regular visits to Palmerston North, Nelson and Hawkes Bay. These initiatives facilitate networking opportunities and the establishment of rapport with general surgery or orthopaedic departments, fostering referrals and joint case collaborations, and potentially laying the groundwork for future specialised units. Trainees who express interest in working regionally can benefit from exposure through such visits, potentially increasing their likelihood of pursuing regional practice.

The development or expansion of further regional plastic surgery centres in New Zealand will require collaboration among key stakeholders, including the Royal Australasian College of Surgeons (RACS), the New Zealand Association of Plastic Surgeons (NZAPS), the Ministry of Health, Health New Zealand and individual plastic surgery units. It is worth noting that the establishment of the last three PRS units (Dunedin, Tauranga and Starship Auckland Hospital) primarily resulted from direct actions by individual surgeons within those hospitals rather than being externally driven (oral personal communication, Brandon Adams, February 2022), highlighting the lack of higher-level advocacy and support from the Ministry of Health.

To reduce barriers to working in regional centres, considerations may include the presence of experienced plastic surgeons, either through them choosing to relocate to regional centres or regularly visiting in an outreach capacity. Outreach surgeons could actively foster relationships with other specialties and departments in regional hospitals, aiming to position plastic surgeons as collaborative and valuable colleagues, thereby facilitating integration and enhancing the regional practice environment. Establishing formal pathways for mentorship, referrals, multidisciplinary meetings and continuous professional development with established units would be ideal to provide support and a sense of attachment for regional surgeons. Once a surgeon is established in a unit, prioritising a trainee to spend time there during training will be crucial to expanding the regional centre in the future.

Addressing financial considerations, including ensuring publicly-funded consultant positions and affordable regional housing, is essential to attracting and retaining plastic surgeons in regional centres. Providing support for family-friendly work environments, including child care and schooling options, is another crucial aspect that should be considered. Financial incentives could be considered to attract surgeons to regional centres, as is common practice in Australia.

Plastic surgery trainees are moved around the country to different training centres—Auckland, Hamilton, Lower Hutt (Wellington), Christchurch and Dunedin—for experience and may work in two to four different cities over the five-year training program. Results from the Australian Medical Training Survey and the New Zealand RACS Training Association Training Evaluation Survey consistently highlight that being forced to relocate for work is one of the biggest causes of stress for trainees. Trainees may therefore be more likely to settle in one area once they have completed training and are less likely to move again for this reason. Employing new consultants in regional centres after completion of training is likely to result in more successful permanent employment compared to attracting them when they are already established as a surgeon, especially if they have already started a private practice.

By addressing the identified barriers and engaging key stakeholders, the plastic surgery community in New Zealand can work towards establishing a more robust and supportive infrastructure for regional centres, ultimately attracting and retaining plastic surgeons in these areas and decreasing inequity of access for patients.

Conclusion

The results of this survey provide insight into the personal and professional factors influencing the career decisions of PRS trainees in New Zealand. The findings highlight the need for strategic workforce planning and engaging relevant stakeholders to address the maldistribution of plastic surgeons, ultimately improving access to specialised care and reducing healthcare disparities for New Zealanders.

Participant consent

Participants have given informed consent to the publication of images and/or data.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding declaration

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Revised: July 11, 2024 AEST