Introduction

Bleeding is a major surgical complication across all specialties that is associated with increased morbidity and mortality. Plastic and reconstructive surgeons place emphasis on preoperative patient evaluation, perioperative care and refining surgical techniques to minimise the risk of bleeding-related complications. Compressions, drains, diathermy devices and haemostatic agents are used to reduce potential dead space and minimise intraoperative bleeding, with the aim of improving patient and surgical outcomes.1,2 While plastic and reconstructive surgery (PRS) procedures have a low rate of bleeding-related complications, the risk of significant blood loss requiring transfusion in complex reconstructive cases, such as microsurgical head and neck reconstructions, remains an ongoing concern.3 Even with strategies in place, bleeding-related complications are often inevitable. Ecchymosis, oedema and haematomas are common postoperative bleeding complications associated with unsatisfactory patient outcomes, poor cosmesis and long-term sequelae.

Tranexamic acid (TXA) is a synthetic lysine analogue that competes with fibrin and reversibly binds with plasminogen, producing an antifibrinolytic effect. During tissue injury, the coagulation cascade produces thrombin, causing fibrinogen to be converted into fibrin and creating a fibrin meshwork essential to the formation of blood clots.4 The prevention of excess fibrin formation and the maintenance of vascular patency is through an enzymatic process known as fibrinolysis.5 In fibrinolysis, tissue plasminogen activator and plasminogen bind to the lysine residues on fibrin, leading to plasmin formation and resulting in fibrin degradation and clot lysis. By reversibly binding with plasminogen, TXA preserves the fibrin meshwork, which inhibits the dissolution of fibrin clots and subsequently prevents bleeding and reduces bleeding severity.6 In addition to its antifibrinolytic properties, TXA has been associated with pleiotropic anti-inflammatory action, resulting in decreased inflammatory markers and analgesia requirements postoperatively.7,8

As an antifibrinolytic agent, TXA is widely adopted throughout surgical specialties as an effective agent for reducing blood loss during surgery. Developed in the late 1950s to treat heavy menstrual bleeding, TXA has been proven in the literature to minimise bleeding in several clinical settings, such as trauma, acute traumatic brain injury and non-cardiac surgeries.9–11 The recent Perioperative Ischemic Evaluation-3 (POISE-3) trial identified that TXA reduced major bleeding in non-cardiac surgery by approximately 25 per cent, significantly reducing the need for transfusion and the total packed red blood cells required for transfusion without any adverse reactions.11 Additionally, TXA has been shown to reduce intraoperative blood loss, leading to improved clarity of the surgical field.12–14 Within Australia, TXA is widely available and relatively inexpensive, costing around AU$10–AU$18 for 2 g.

In Australia, TXA has Therapeutic Goods Administration approval for heavy menstrual bleeding, hereditary angioneurotic oedema and patients with coagulopathies undergoing minor orthopaedic arthroplasty, cardiac and prostate surgeries. It is available in intravenous (IV), oral or topical formulations and is well-tolerated with few contraindications and side effects listed. Side effects include nausea, vomiting and diarrhoea. Primary concerns of TXA administration relate to its potential to increase the risk of thrombotic events, due to the inhibition of fibrinolysis, and seizures, given its ability to cross the blood-brain barrier and inhibit glycine receptors.15,16

While bleeding risk is comparatively lower in PRS procedures compared to other specialties, the benefit of TXA use should be considered. There is a lack of standardised guidelines and recommendations regarding the optimal dosing, route and timing for TXA administration in PRS procedures.

In this study, we conducted a comprehensive survey to determine the current usage of TXA by Australian plastic and reconstructive surgeons and provide a foundation to guide future discussions for national recommendations for TXA use.

Methods

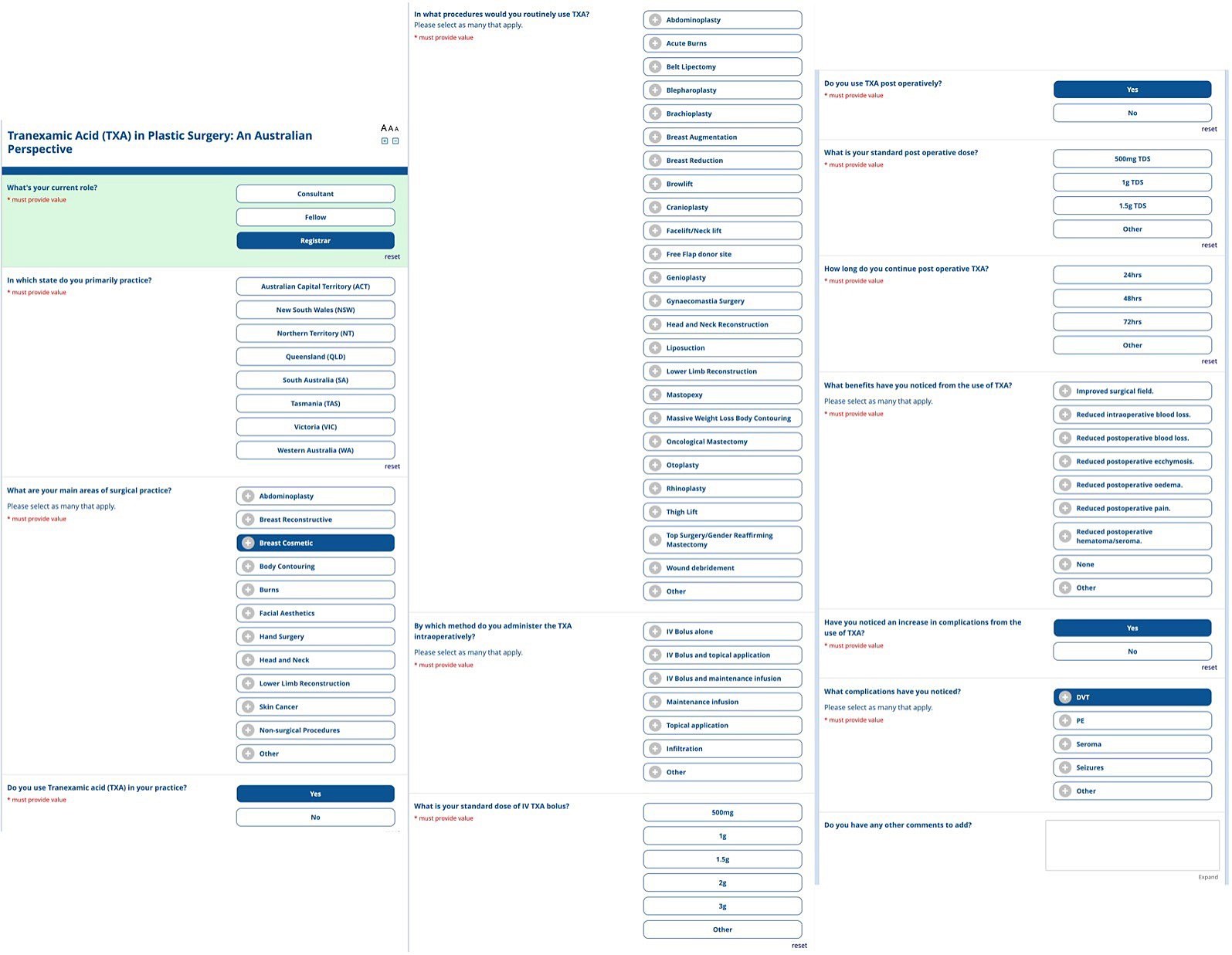

We reviewed the literature surrounding TXA use in PRS, including international recommendations for dosages in adults having inpatient surgery2 and a survey distributed to the British Association of Aesthetic Plastic Surgeons,17 to develop a 24-point questionnaire. The questionnaire aimed to get information from Australian plastic and reconstructive surgeons about their use of TXA in their current practice, including dosing, routes of administration, and perceived benefits and complications.

The questionnaire included a series of multiple-choice questions and additional free-text questions to collect objective and subjective information. Free-text options were included where appropriate to allow respondents to provide further information. The final questionnaire has been attached at Figure 1. The estimated time for completion was, on average, three minutes per completed questionnaire.

A voluntary, anonymous questionnaire was distributed electronically from May to July 2023 using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at Chris O’Brien Lifehouse. REDcap (Research Electronic Data Capture) is a secure, web-based software platform. The survey was distributed to all members of the Australian Society of Plastic Surgeons and the Australasian Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgeons. The questionnaire responses were tabulated and examined using descriptive statistics.

Results

Respondent demographics

The questionnaire was sent to 543 Australian plastic and reconstructive surgeons, with 62 responses received (overall response rate of 11%). Responses were obtained from plastic surgeons across Australia. The majority of respondents were from New South Wales (32%), Victoria (29%) and Queensland (15%), similar to the Australian distribution of plastic surgeons according to the National Health Workforce Dataset.18

Of the responding plastic surgeons, 90.3 per cent (56/62) used TXA in their daily clinical practice for a variety of PRS procedures (see Table 1). The most common procedures included breast reduction (37%), abdominoplasty (35%), massive weight loss procedures (25%), and face/neck lifts (22%). Under ‘other’ procedures, topical TXA was noted for non-surgical injection procedures and pharyngoplasty orthognathic surgery.

TXA preparation and dosing

The most common method of administering TXA was through a single IV bolus (63%), followed by IV bolus and topical application (23%), topical application only (9%), infiltration dose (3%) and IV bolus followed by a single intraoperative dose (1%). None of the respondents used a maintenance infusion.

Of those who administered an IV bolus, 82.3 per cent used a 1 g dose, 10.6 per cent used a 500 mg dose and 6.3 per cent used a 2 g dose. Topical TXA administration varied from 1–2.5 mg/mL. The most common standard topical concentration of TXA was 0.25 mg/mL and the standard infiltration concentration ranged between 1.0 and 2.5 mg/mL. Postoperatively, the administered dose varied between respondents. One-eighth (12.5%) of respondents used a 1 g (either IV or oral) dose three times a day for 24 hours. Respondents indicated that postoperative administration and dosing would depend on the surgical procedure and postoperative bleeding. Large surface area procedures require a 24-hour, three times a day administration, while smaller cases only require a single dose postoperatively.

Benefits and complications of TXA

Of the surveyed plastic and reconstructive surgeons, 89.3 per cent noticed clinical benefits of using TXA within their practice, 6.5 per cent perceived no benefit in incorporating TXA in routine use and one respondent said it was too early to identify a clinical benefit. The main benefits of using TXA were reduced postoperative and intraoperative blood loss, reduced postoperative haematoma/seroma and improved surgical field. Table 2 details the perceived benefits of TXA use. One respondent reported a complication, with an increase in postoperative bruising following breast surgery (reduction/mastopexy) but not following abdominoplasty/liposuction procedures. Additional comments made by respondents regarding TXA use in their practice were categorised into the themes of cost-effectiveness, clinical benefit and safety profile.

Discussion

Our study aimed to provide a national picture of the use of TXA in PRS, identify the procedures routinely using TXA and identify the benefits perceived by Australian plastic and reconstructive surgeons. We found that 90.3 per cent of respondents used TXA in their daily clinical practice. In Australia, TXA is marketed and approved by the Therapeutic Goods Administration as an antifibrinolytic and its ‘off-label’ use in reducing perioperative blood loss in PRS procedures has been advocated by many authors. While its benefit in PRS procedures has been cited in the literature, the lack of clear clinical guidelines and level 1 research has precluded its widespread adoption. This includes variability in the literature of optimal routes of administration and dosages for different types of surgical procedures.

The most common route of administration and dose by Australian plastic and reconstructive surgeons is an initial 1 g IV bolus followed by either a topical or infiltration dose or a further postoperative 1 g IV bolus. Early in vitro studies on TXA have suggested a concentration of 10 μg/mL in vitro is necessary to inhibit fibrinolysis (approximately 10 mg/kg to prevent 80 per cent of the plasminogen activation),19 whereby a 1 g IV bolus would remain above the therapeutic threshold in the majority of patients. A 1 g IV bolus pre- and postoperatively was the recommendation following the POISE-3 trial for all patients at risk of bleeding undergoing non-cardiac surgery and by an implementation group in the UK consisting of the Royal College of Surgeons of England, Royal College of Anaesthetists and Royal College of Physicians.11,20

Among respondents, breast procedures, facial plastic surgery (face/neck lifts, rhinoplasty) and body contouring procedures (after massive weight loss, abdominoplasty, belt lipectomy) are the most common procedures using TXA in routine clinical practice. This finding is similar to that of plastic and reconstructive surgeons in the United Kingdom and the United States.17,21

Postoperative haematoma and seromas are the most frequent complications following breast surgery.22–27 For patients undergoing breast reconstruction, complications from excess blood and seroma accumulation on the mastectomy bed or around the breast implant create a proinflammatory environment, increasing the risk of bacterial infection and poorer surgical outcomes.28,29 A recent systematic review and meta-analysis about TXA use in breast surgery concluded there was a significant reduction in the formation of postoperative haematoma and seroma in patients undergoing mastectomy with implant or free flap-based reconstruction when TXA was given.30 Despite limited level 1 research on the benefits of TXA use in breast surgery, the positive results favour its consideration in routine clinical practice30–32 and our study shows that plastic and reconstructive surgeons commonly use TXA in breast surgery.

Significant differences exist in the administration and dosing strategies of TXA in breast procedures. For implant and free flap breast reconstruction procedures, IV and topical TXA administration has shown benefits in reducing bleeding-related complications. These TXA dosing protocols include a single 1 g IV dose,33 1 g IV pre- and postoperatively,34 2 g intraoperatively, 1 g 24-hours postoperatively35 and a 10 mg/kg IV dose preoperatively followed by a 1–5 mg/kg/hr infusion.36 A double-blinded randomised control trial (RCT) investigated the topical use of 3 per cent TXA on the mastectomy bed prior to implant insertion in patients undergoing immediate direct-to-implant reconstruction, finding a significant decrease in bleeding-related complications and drain output.32 Furthermore, the topical use of TXA in breast augmentation may be associated with reduced capsular contracture rates, the most common reason for revision surgery following breast augmentation.37 In reduction mammoplasties, studies have shown effective protocols of topical administration of 25 mg/mL TXA at the wound surface with no observed adverse reactions.31

In face lifts, haematoma formation is the most common postoperative complication with incidence ranging from 0.2 to 8 per cent.38 Implementing TXA through TXA-soaked gauze, subcutaneous or IV administration has been suggested to reduce bleeding-related complications in the facial region.39,40 A prospective double-blinded RCT using a 1 g IV pre- and postoperatively showed a significant reduction in postoperative collections, oedema and ecchymosis; however, a clear reduction in intraoperative blood loss was not concluded.41 Studies have shown a benefit from a subcutaneous infiltration of 1 or 2 mg/mL of TXA with an 0.5 per cent lidocaine/1:200,000 epinephrine solution, with reduced intraoperative blood loss, decreased drain output and theatre time.42–44 For rhinoplasties, the initial 1 g IV bolus and topical TXA added to anaesthesia or oral TXA pre- and postoperatively have been described as beneficial.45,46

Optimal administration and dosing in these procedures is not conclusive. While the literature suggests TXA significantly reduces postoperative oedema and ecchymosis following facial plastic surgery, its significance needs further evaluation.46 According to our findings, TXA is commonly used in face lifts and rhinoplasties by Australian plastic and reconstructive surgeons, a finding similar to their international colleagues.17 The difference in TXA use between face/neck lifts and rhinoplasties could be due to preferences in procedure choice among plastic and reconstructive surgeons, however, this could not be elucidated further.

The respondents commonly use TXA for body contouring surgery (including abdominoplasties, belt lipectomies and liposuction) and massive weight loss procedures.

There is limited literature on the use of TXA in body contouring procedures, with significant differences in routes of administration and dosing. However, the available literature shows promising results with TXA use reducing haematoma incidence, drain output and seroma formation.19 For body contouring procedures, single pre- and postoperative IV boluses, IV boluses with TXA in local tumescence or topical administrations have shown varying clinical benefit. A prospective double-blinded, non-randomised study showed an IV dose of 10 mg/kg of TXA pre- and postoperatively would decrease the total volume of blood in the total lipoaspirate and allow for the aspiration of more fat during liposculpting.29 Similarly, a double-blinded RCT looking into power-assisted liposuction mammaplasty using a combined 500 mg IV bolus followed by local infiltration, 5 mL of 0.5 g/5 mL TXA with 1:100,000 epinephrine, presented a reduction in the volume of blood in the total lipoaspirate.47 While clinical benefit is described in the literature, a review of 435 patients undergoing trunk aesthetic surgery (abdominoplasty, belt lipectomy and body contouring surgery) found no significant difference in complications with TXA use; however, there was a significant decrease in intraoperative time and overall length of hospitalisation.48 There is a need for multicentre prospective RCTs to evaluate the administration routes, dosages and perceived clinical and patient benefits of TXA use in body contouring surgery.

Patients undergoing massive weight loss procedures represent a cohort at a higher risk of surgical and postoperative complication.49,50 Therefore, factors to mitigate the risk of complications should be considered. In massive weight loss patients with large wound surface areas, topical application of TXA with 20 mL of 25 mg/mL solution or by administration of a bolus of 200 mL of 5 mg/mL into the wound cavity, showed adequate clinical effect when compared to 1 g IV bolus groups.51

Primary concerns regarding the use of TXA were the potentially increased risk of thrombotic events (due to the inhibition of fibrinolysis) and seizures. These concerns have been explored in recent literature. A meta-analysis with 216 studies involving over 125,550 people undergoing surgical procedures with IV TXA did not identify an increased risk, irrespective of TXA dose.52 A similar meta-analysis with over 100,000 patients concluded there was no increased risk of thrombotic events or seizures, specifically TXA did not appear to increase the risk of seizures at doses less than 2 g/day. However, it was noted there may be a dose-dependent increased risk of seizures and very high doses should be avoided (more than 4 g/day).53

Specific mitigation strategies to reduce the risks of thrombotic events when using TXA include to avoid its use in patients with active thromboembolic disease or those with a significant history of thrombotic events, and to use mechanical prophylaxis measures such as intermittent pneumatic compression devices during surgery to reduce the risk of venous thromboembolism. In relation to reducing the risk of seizures, mitigation strategies include limiting doses to 2 g/day or less, administering TXA as a slow infusion rather than a rapid bolus to reduce peak plasma concentrations that may lead to seizures, and using TXA topically, where appropriate, to achieve haemostasis without the systemic exposure associated with higher seizure risk.

Limitations in this study include that the questionnaire has only been completed by members of the Australian Society of Plastic Surgeons and the Australasian Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgeons with responder or reporting bias for the questionnaire among plastic and reconstructive surgeons who have seen benefits of routine TXA use. Another limitation is that the short-form questionnaire does not allow respondents to discuss their TXA administration and dosing strategies in detail. The response rate of 11 per cent, while higher than the average response rate for a similar questionnaire, does not capture the viewpoints of the majority of Australian plastic and reconstructive surgeons.

Conclusion

Tranexamic acid is an inexpensive and effective antifibrinolytic agent that has been widely adopted throughout surgical specialties to reduce blood loss and bleeding-related complications. While still novel in its adoption in PRS procedures, it has been implemented in routine clinical use by many Australian plastic and reconstructive surgeons. The widespread use of TXA by Australian plastic and reconstructive surgeons suggest there may be benefit in its use. However, it must be accepted that future research and efforts are needed to determine the minimal effective dose of TXA that minimises bleeding without significantly increasing the risk of venous thromboembolism and seizures and to investigate the comparative efficacy and safety of different routes of administration. This would allow the development of clinical guidelines for the use of TXA.

Follow-up

To more fully capture how TXA is being used in PRS, the authors have reopened the questionnaire and would encourage Australian plastic and reconstructive surgeons to complete it. The questionnaire is available at https://redcap.lifehouserpa.org.au/surveys/?s=3FTKWXHCPEERYKERq until August 31, 2025.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding declaration

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Revised: May 31, 2024 AEST; August 16, 2024 AEST