Introduction

Silicone migration associated with silicone breast implants is a recognised phenomenon, resulting in lymph node deposits, and subcutaneous (chest wall, abdomen, and into the upper and lower extremities), visceral (including lung, hepatic and splenic deposits) and ocular granulomata.

We describe a unique case of frank silicone accumulation in contiguous distant sites, across a remarkably broad front, following direct chest trauma. The silicone deposits were associated with invasive and erosive characteristics.

This report highlights the importance of careful preoperative evaluation of any woman with longstanding breast implants who suffers chest trauma and reviews the mechanisms of silicone migration.

Case

A 64-year-old woman presented with 42-year-old subpectoral silicone breast implants. She was referred with pain following a fall associated with extensive bruising to the left chest and hip. An MRI four years prior to presentation was reported as showing no radiological evidence of rupture.

Clinical examination demonstrated a classic ‘waterfall’ cosmetic change, with a firm mass (with overlying skin changes) lateral to the left inframammary fold extending posteriorly and a second mass overlying the left iliac crest.

Differential diagnoses considered included chronic haematomata with organising fibrosis or an undiagnosed malignancy.

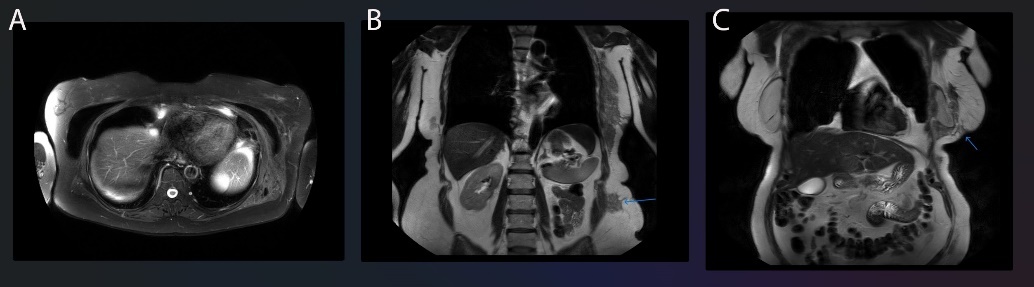

An MRI performed with gadolinium contrast and specific silicone selective sequences demonstrated extensive silicone migration along fascial planes, in a contiguous mass measuring at least 28 cm craniocaudally (Figure 1).

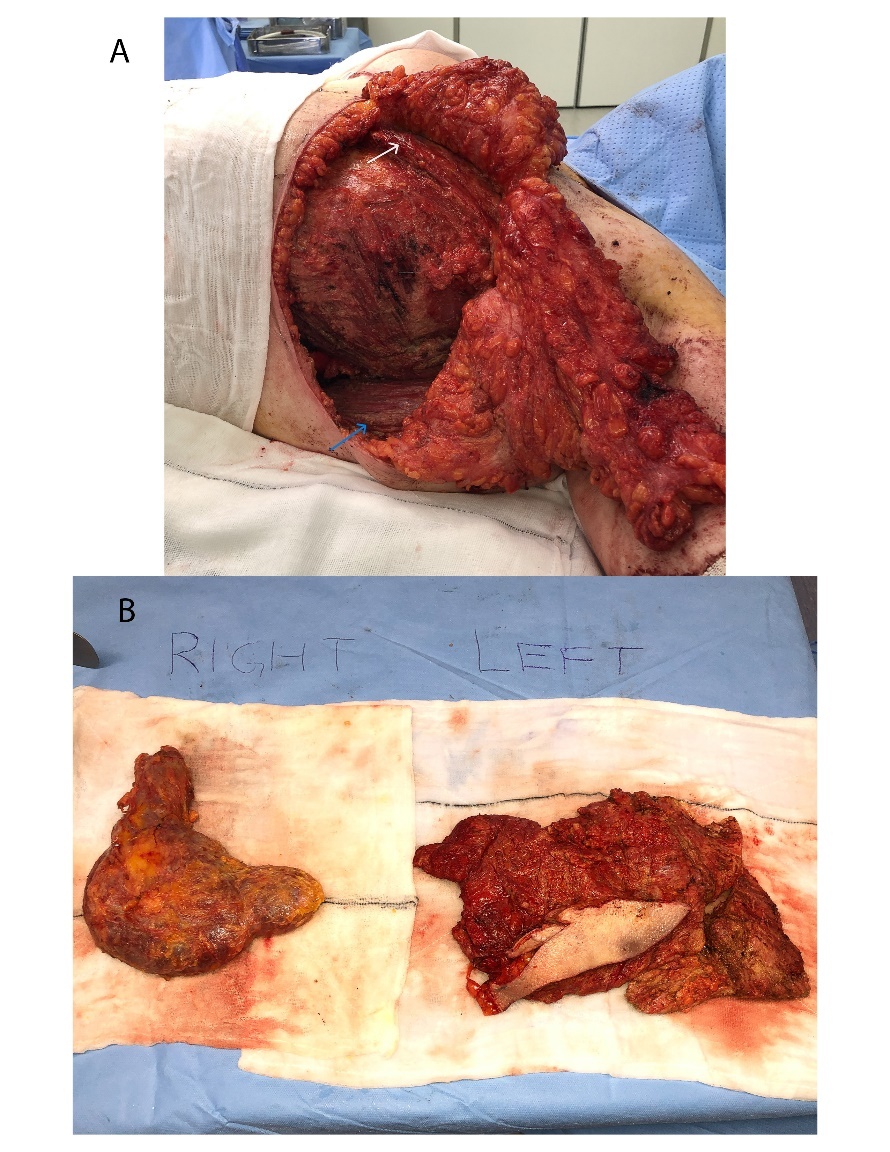

The patient subsequently underwent removal of the implants with total capsulectomy and extensive debridement of macroscopic silicone deposits (Figure 2).

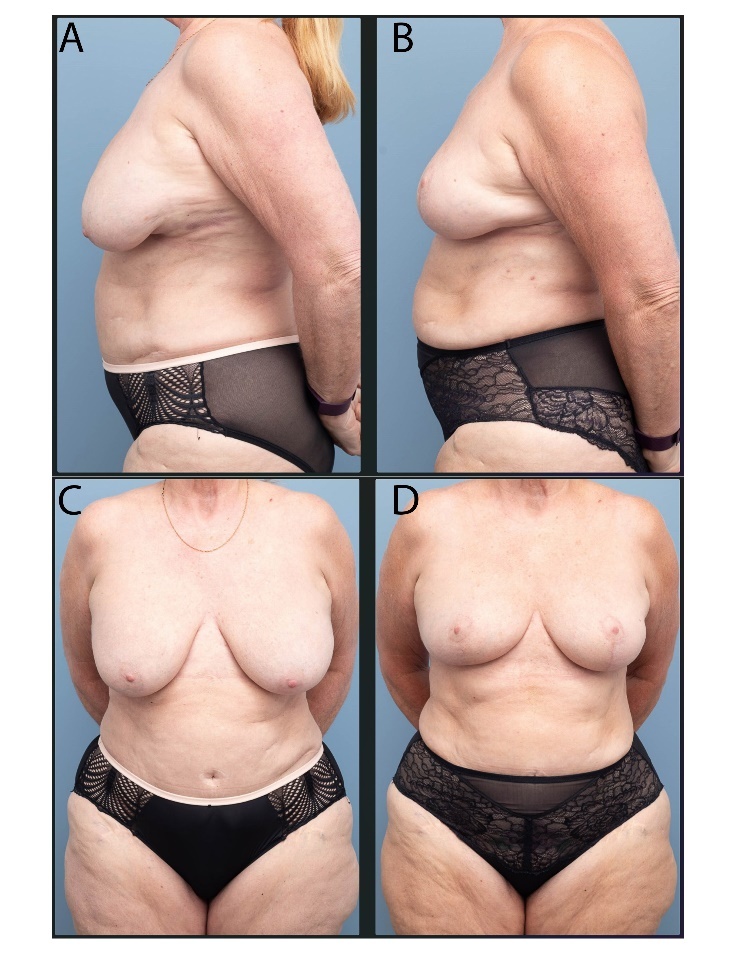

A concurrent mastopexy was performed with a laterally pedicled auto-augmentation flap and a superior nipple-areolar complex pedicle.

The patient recovered well with a satisfactory aesthetic outcome (Figure 3).

Discussion

Silicone escape: gel bleed, surface shedding and rupture

Intracapsular silicone breast implant rupture is most commonly silent, without associated symptoms or signs.

Silicone gel bleed occurs when low-molecular-weight silicone polymer migrates through pores in the more highly cross-linked elastomer shell,1 resulting in accumulation of silicone within the implant capsule and in extracapsular tissues. Extracapsular silicone may therefore be present in the absence of implant rupture. Length of implantation time is closely related to increased molecular mobility.

Microscopic silicone is observed within capsules of all silicone-filled and saline-filled macrotextured devices, but not with saline-filled smooth-surface devices. Silicone bleed, rather than silicone shedding from the shell surface, appears to play a dominant role in silicone movement into and beyond the capsular tissue.2 Silicone particulate shedding from macrotextured implant shells does also occur and results in larger, albeit fewer, silicone deposits. Microscopic silicone deposits may be present external to the capsule in up to 87 per cent of women with silicone breast implants3 irrespective of rupture.

Extracapsular rupture is typically encountered clinically as an extension of the fibrotic capsule (as seen with the right breast capsule in Figure 2).

Mechanisms of silicone dissemination

It is theorised that silicone dissemination follows both lymphatic and haematogenous routes.

Haematogenous spread may result in pulmonary silicone emboli,4 which have been described following both silicone injections and silicone breast implant placement.

Lymphatic spread is along standard drainage pathways to regional and remote lymph nodes, and may be present irrespective of implant integrity.

Silicone dissemination from breast implants has been associated with discrete lesions in the trunk, upper5 and lower extremities,6 the face and orbit.7 Macroscopically, these lesions are small (1–5 cm diameter), circumscribed and granulomatous in nature.6 The specific mechanism underlying such deposits is unknown.

Deposits of free unencapsulated silicone are described following the injection of liquid silicone. The pathophysiological response to free liquid silicone is distinct to the response to silicone breast implants, with a lack of capsule formation noted and extensive granulomatous inflammation.8

The described case is of note due to the presence of extensive unencapsulated free silicone outside the breast associated with a silicone breast implant rather than liquid silicone injections.

Immune response to silicone

While historically considered biologically inert, silicone is now well established as a potential inflammatory stimulant.

Surface roughness and silicone debris, as opposed to free silicone or gel bleed, are associated with a more profound inflammatory response.9 Reduced roughness is a mitigating factor in the development of capsular contracture,10 mirroring clinical experience with current generation nanotextured devices.

Presentation and investigation of silicone dissemination

The challenge of disseminated silicone migration varies according to the indication for breast implants.

Following implant-based reconstruction after mastectomy, disseminated silicone within the breast or nodal involvement requires exclusion of cancer recurrence.

Disseminated silicone from cosmetic breast implants may mimic primary malignancy and present with a palpable mass in the breast leading to a requirement for invasive diagnostic procedures. Isolated silicone adenopathy is readily diagnosed with ultrasound and may or may not be symptomatic. Routine excision of enlarged lymph nodes due to a foreign body response would not be indicated.

Investigation of implant rupture or silicone migration is with ultrasound and MRI. The author, like many other plastic surgeons, uses handheld, high-resolution ultrasound in rooms for diagnosis or exclusion of rupture by specific assessment of the implant shell. MRI may be indicated in some situations, including cases which demand the exclusion of malignancy. Breast-specific MRI with gadolinium contrast and silicone-specific sequences offers high specificity and sensitivity for rupture and, as demonstrated in this case, MRI is the only investigation capable of delineating silicone dissemination.

Trauma may be a cause of distant migration of silicone.5 Direct chest trauma has been reported in 67 per cent of patients with distant silicone migration. Rupture likely precedes trauma in most cases, but impact may force a breach in the previously intact capsule with escape of silicone into surrounding soft tissues. We strongly recommend MRI be considered in women with longstanding breast implants who present with a history of chest trauma.

Conclusion

The case presented here is unique in the extent of pooled free silicone (rather than discrete granulomatous lesions) and the contiguity of the silicone deposition over a remarkably broad front. Tracking and pooling of free silicone along fascial planes has not been described and represents a therapeutic challenge due to the scope of resection and the impact on subsequent reconstructive procedures. Presentation of an implant rupture with a mass demands careful assessment, and surgeons should retain an open mind with regards to the extent of silicone migration, especially when chest trauma is reported. MRI remains the preferred investigation in such cases. Flexibility in the approach to mastopexy at the time of explant may be necessary to accommodate more extensive surgical access and debridement.

Patient consent

Patients/guardians have given informed consent to the publication of images and/or data.

Conflict of interest

The author has no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding declaration

The author received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Revised: September 27, 2024 AEST