Introduction

Symptoms of rectus diastasis include back pain, weakness, urinary incontinence and abdominal bulge. These symptoms are associated with a reduced quality of life.1 Some studies show a correlation between the degree of rectus diastasis and lumbopelvic pain2 and there is evidence to suggest that surgical correction of rectus diastasis in symptomatic individuals improves their symptoms.3

In July 2022 the Medicare Benefits Schedule (MBS) Review Taskforce announced a raft of changes and consolidations of existing MBS item numbers relating to plastic surgery procedures.4 Included in these changes was the introduction of item 30175 regarding the procedure for a radical abdominoplasty with repair of rectus diastasis, excision of skin and subcutaneous tissue, and transposition of umbilicus. In order to meet the criteria of this benefit, the patient is required to have a preoperative radiological assessment of their abdomen showing a rectus diastasis with inter-rectal distance (IRD) of at least 3 cm. In many cases, the surgeon will specifically request an abdominal ultrasound to assess the extent of rectus divarication and ascertain whether or not the patient can qualify for the Medicare benefit. For the surgeon, knowing whether or not the patient qualifies for the Medicare benefit is an important part of surgical planning and it is significant for the patient as it affects the total out-of-pocket cost they ultimately pay for the procedure. A patient who does not meet the MBS criteria may choose to forgo or postpone surgery as a result of the cost difference.

The IRD varies in different body positions, postures and states of respiration.5,6 It also is variable along the length of the rectus abdominus.7 There is no internationally adopted standard of classification of rectus diastasis; however, multiple classifications have been proposed.7–10 Previous studies have assessed the reliability of clinical examination of IRD compared with ultrasound with mixed results.11–13 Interestingly, all of these studies assume that the ultrasound result is the accurate benchmark against which clinical findings are compared. Mendes and colleagues challenged this assumption in 2007 with a study of 20 patients comparing ultrasound and in vivo intraoperative measurements of the IRD for patients undergoing abdominoplasty at seven levels along the linea alba. They found that below the umbilicus there was a significant difference between ultrasound measurement compared to intraoperative measurement when the radiological value was less than the in vivo value.14

As a result of the importance of accurate preoperative measurement of the IRD for patients having surgery in Australia seeking to meet the requirements of the MBS, this paper aims to re-evaluate the relationship between preoperative ultrasound evaluation of the IRD and intraoperative measurements for patients undergoing abdominal wall procedures.

Methods

Ethics approval was given by the Epworth Research Ethics Committee (approval number EH2024-1087).

Inclusion criteria were patients aged 18 years and older who underwent abdominal skin procedures with rectus diastasis repair post massive weight loss or post pregnancy. Only patients who had preoperative ultrasound assessment of their rectus diastasis from March 2022 to April 2024 were included.

Abdominal skin procedure was defined as either the abdominal part of a body lift procedure or an abdominoplasty as a single procedure.

The IRD was defined as the distance between the two medial edges of the rectus abdominus muscle.

The maximum IRD value recorded in the radiology report was used for analysis. The location of the maximum IRD in the radiology report was either above, below or at the level of the umbilicus. When the radiology report did not specify the location of the IRD in relation to the umbilicus, the authors determined the location using the ultrasound images available in the image viewer.

Intraoperative measurement of the IRD was undertaken by the authors with the use of a sterile ruler. Measurements were made at the reported location of the radiological IRD along the rectus. For example, a radiological report stating that the IRD was measured at the umbilicus would be paired with the intraoperative measurement taken at the umbilicus.

Analysis was undertaken using a paired t-test as residuals formed a Gaussian distribution.

Results

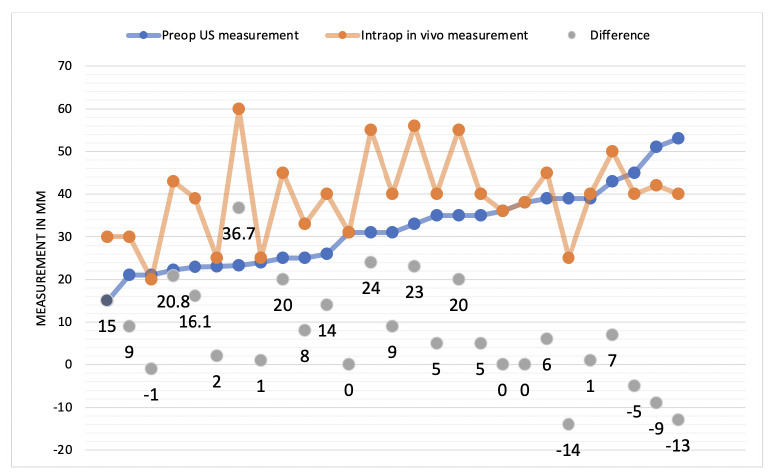

Overall, 27 patients, all female with a median age of 52 (range 30.2–58.9), were included in the study (see Table 1). Preoperative ultrasound was undertaken by 27 patients and a chart of the paired values is shown in Figure 1. On average, preoperative ultrasound significantly underestimated the IRD (mean = 31.9 mm, SD = 9.6) compared to intraoperative measurement (mean = 39.4, SD = 10.2). The statistically significant mean difference between matched intraoperative and preoperative radiological IRD measurements was 7.43 mm, t26 = 3.23 (p = 0.003; 95% CI = 2.7–12.12).

Discussion

The results of this study show a significant underestimation of ultrasound evaluation of the IRD compared to intraoperative measurements and are consistent with the findings of Mendes and colleagues.14 The main strength of this study is its simplicity. All cases were performed and measured in the same manner by three surgeons at a single institution reducing the risk of measurement bias.

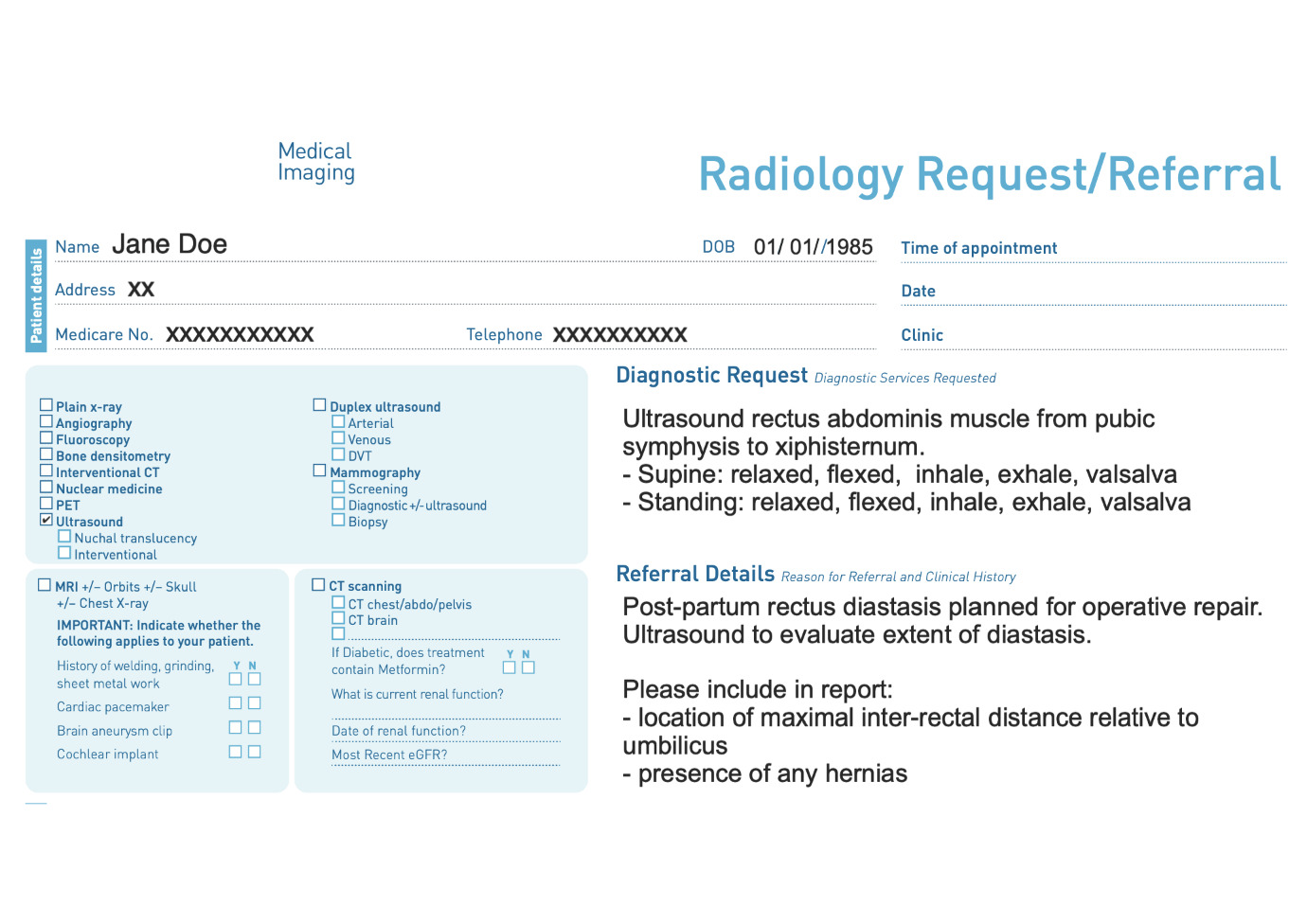

Weaknesses of this study are the heterogeneity of the ultrasound measurements. Ultrasound studies were performed with different equipment by different providers working at different sites. Ultrasound request forms are also not standardised. Reporting was verified by different radiologists. The heterogeneity surrounding preoperative ultrasound is significant. Given that the MBS item number 30175 is relatively new, there is a lack of familiarity among sonographers and radiologists as to the reason for the investigation. The patient’s position, phase of respiration, presence of Valsalva and completeness of assessment along the entire vertical length of the rectus are not standardised but are all relevant features of the investigation. Awareness of the indication of the scan also influences the detail of the final report. It can be a frustrating experience for a clinician to receive an ultrasound report that simply states ‘22 mm rectus diastasis’ without mention of a vertical level relative to the umbilicus and to then subsequently find a much larger supraumbilical diastasis intraoperatively. The mostly likely reason for this is that, in a non-standardised investigation, the sonographer has simply chosen any location along the vertical length of the rectus to assess for diastasis. In two cases, the authors were required to assess if the IRD value was above, below or at the level of the umbilicus as it was not mentioned in the final report. Over time, the local sonographers and radiologists became more thorough in their examination and reporting due to repeated requests from the principal authors for more detailed reports. A rectus diastasis request form that includes standardised protocol and definitions may increase the accuracy and relevance of a preoperative ultrasound assessment for rectus diastasis. We have provided an example of a detailed preoperative ultrasound request form in Figure 2.

The magnitude of the IRD is positively associated with symptom severity2; however, preoperative measurement of the exact length of the IRD in rectus diastasis has limited clinical significance. It may be important to have accurate ultrasound measurements of the IRD for operative planning especially in the event of a large diastasis. Surgeons may not be able to directly plicate a large diastasis and may opt for a mesh or component separation technique. This would be a decision that should ideally be informed by an accurate investigation and discussed with the patient preoperatively. In general, most rectus abdominus diastases and any concurrent hernias can be identified and repaired without the aid of preoperative ultrasound.

There are a number of speculative suggestions that can be made for the discrepancy between the radiological and in vivo measurements of the IRD. Anaesthetic medication, including muscle relaxants, may exaggerate the IRD intraoperatively compared to the awake patient’s rectus abdominus under the pressure of the ultrasound probe. Another theory is related to the surgery itself. The dissection and separation of the anterior abdominal wall from the abdominal skin, fat and fascia creates a changed anatomical state compared to the time of the ultrasound. It is possible that surgical exposure allows for exacerbation of the IRD in rectus diastasis purely by release of the many ligamentous connections between the abdominal wall and its overlying skin. One final theory is that the apparent difference is a result of measurement bias between sonographers, who have no stake in the outcome of the measurement, compared to surgeons who may be inclined to err on the larger value in the event of ambiguity of the precise location of the medial rectus edge.

Ultrasound is a valid, commonly-used imaging modality to assess rectus diastasis.15,16 The advantage of ultrasound over other modalities is its ability to measure dynamic change in the rectus abdominis.6 The findings from this paper do not challenge the validity of ultrasound as a tool in measuring IRD in rectus diastasis but rather highlight a glaring need for standardisation of the protocol for evaluating IRD.

Conclusion

There is a significant discrepancy between radiological and in vivo measurements of the IRD in patients with rectus diastasis. Surgeons can expect to find larger in vivo diastasis compared to preoperative radiological values. Standardisation of ultrasound examination and reporting of rectus abdominus diastasis may reduce this discrepancy.

Patient consent

Patients/guardians have given informed consent to the publication of images and/or data.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding declaration

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Revised: October 14, 2024 AEST