Introduction

Keloids can form after trauma, burns or cosmetic piercings, and they present a unique set of problems for the surgeon and patient. Keloids commonly form on sites that are regularly stretched by daily movements, including over large joints, and the anterior chest, scapula and lower abdomen.1 Risk factors associated with keloid formation have recently been identified (including genetics, the presence of oestrogen and some lifestyle factors), allowing for a more targeted and effective approach to treatment and prevention.2 There have been significant developments in understanding the pathophysiology of keloid formation, which is now known to be caused by chronic inflammation in the reticular dermis. Keloids are a fibroproliferative disorder characterised by continuous inflammation, excessive angiogenesis and collagen accumulation within the reticular dermis.3 On a histological level, keloids contain keloidal collagen while hypertrophic scars contain only nodules. Many scars present with a combination of both types of tissue, which may indicate that keloids and hypertrophic scars are the two extremes on a spectrum of scarring.2 It is thought that the interaction between known risk factors and the intensity and duration of inflammation in the reticular dermis determines the propensity to develop hypertrophic scars or keloids in different patients.4 Treatment options range from silicone dressings, topical agents, steroid injections and immunosuppressive therapy to radiotherapy and surgery in extreme cases.2 Many keloids are resistant to treatment or recur, presenting a significant and ongoing issue for patient and surgeon.

We present a new approach to keloid excision, which aims to minimise tension and inflammation in the reticular dermis by splitting the dermal layer to promote hypereversion of the resulting wound edge. Eversion of the split-dermis promotes superior cosmetic outcomes by counteracting the contractile forces of scarring that lead to either an indented or a hypertrophic scar.5–8 Additionally, a deckled (fine S-wave) incision line9,10 disrupts the longitudinal lines of tension, producing an aesthetically superior scar.10,11 The combination of split-dermis hypereversion, scanty intraoperative steroid injection and deckled incision line minimises the appearance of the resulting scar and promotes tension-free wound closure with minimal inflammation of the reticular dermis. This is ideal for the treatment of keloids.

Operative technique

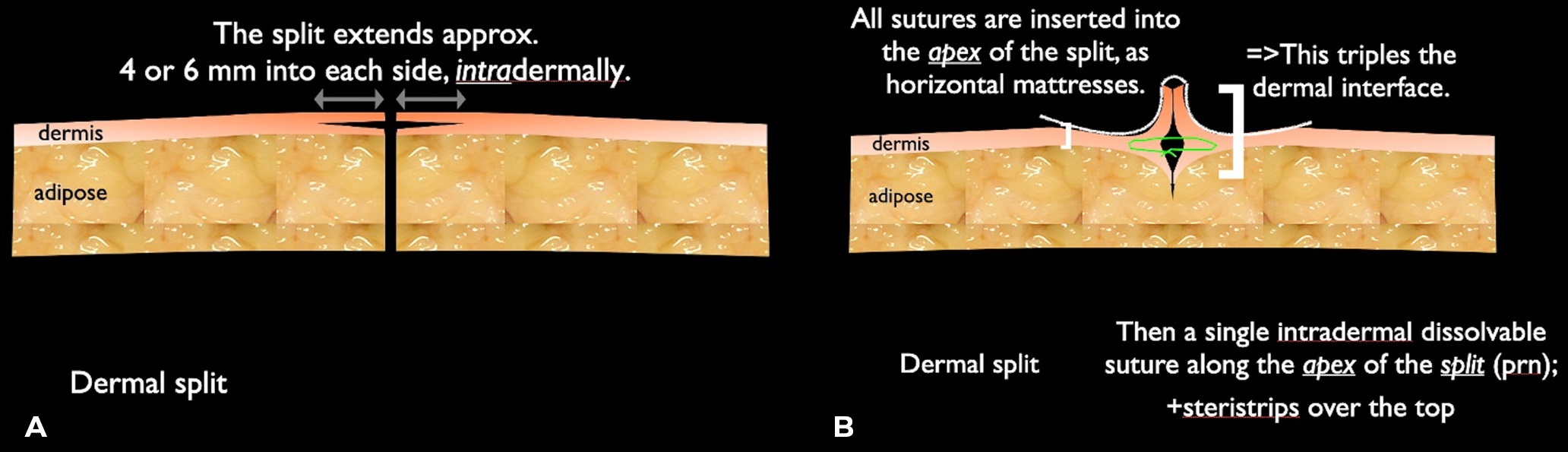

The keloid is marked preoperatively and completely excised with deckled incisions, using a number 15 blade or ideally a 15-degree ophthalmic blade. The new wound edges are incised at the level of the mid-dermis for 4–6 mm laterally (Figure 1). The apex of this mid-dermis plane is then apposed together using a 6-0 Maxon (Medtronic, Plc) or polydioxanone (Ethicon, Inc) suture to promote a ridge of split-dermis externally (and internally), with 6-0 polypropylene (Ethicon, Inc) suture applied to the skin (Figure 1). A small amount of Kenacort-A 10 or Kenacort-A 40 (Aspen Pharmacare Australia Pty Limited) for large keloids is injected into the apex of the split-dermis to further suppress any keloid recurrence. The skin sutures are removed four to five days postoperatively. Regular follow-up is vital for these patients, as any early sign of recurrence, usually presenting as a very slight firmness, can often be treated with another injection of Kenacort-A 10. Patients should be educated to recognise the early signs of recurrence and inform their surgeon so that recurring keloids are detected and dealt with quickly.

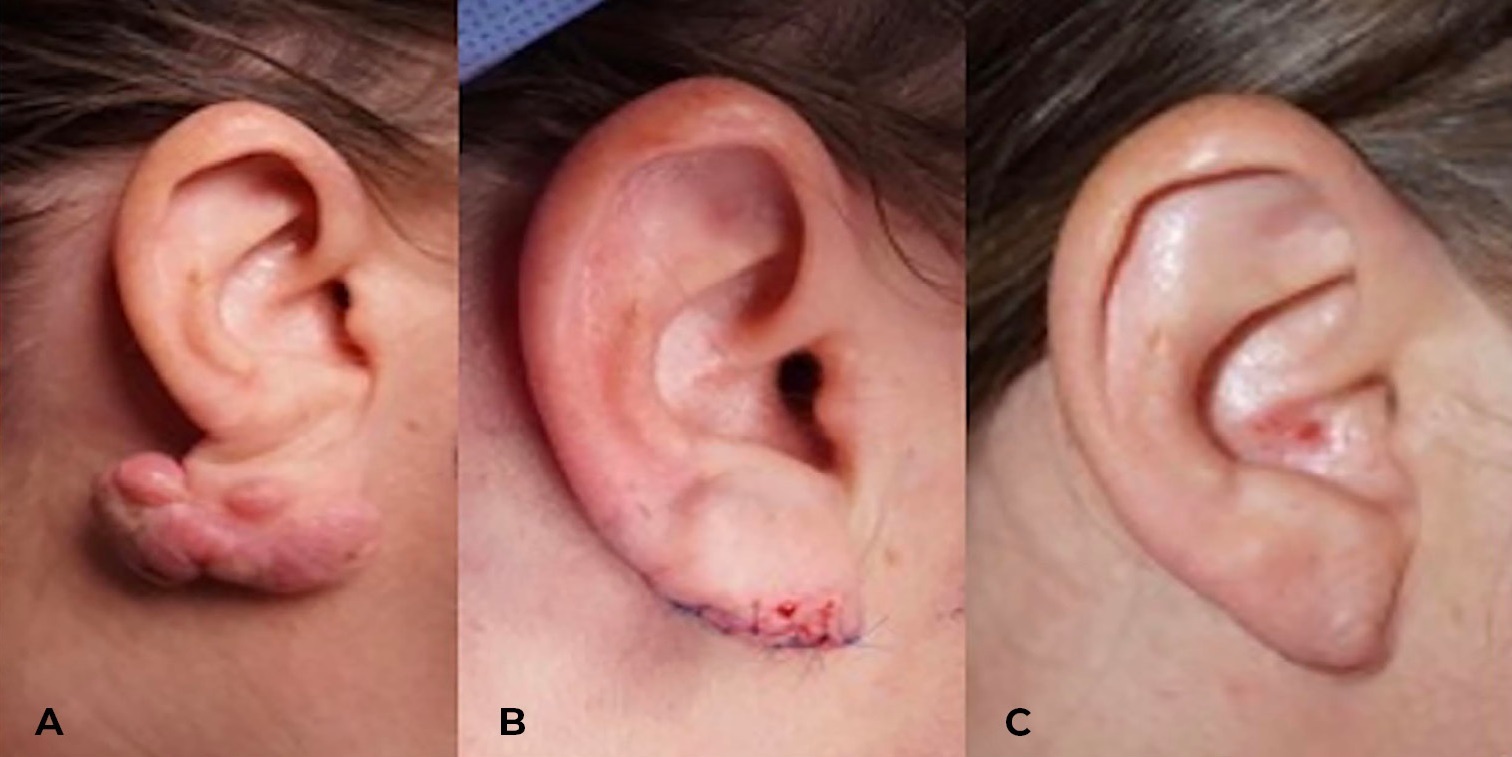

A 39-year-old woman presented with a pedunculated keloid of the earlobe following trauma caused by cosmetic ear piercing (Figure 2A). She underwent excision of the keloid with split-dermis repair and intralesional injection of Kenacort-A 40 (Figure 2B). She had an uneventful recovery and presented 14 months later for a regular follow-up (Figure 2C). At that visit, some very slight firmness deep inside the earlobe was noted and injected with 0.2 ml Kenacort-A 10, and instructions were given to return for a follow-up if she notices any further firmness.

Discussion

Keloids represent a complex and often challenging condition in plastic surgery, characterised by their tendency to extend beyond the boundaries of the original wound. While they are generally benign, their potential for causing discomfort and aesthetic concerns underscores the need for effective management strategies. Advances in treatment, including surgical excision, steroid injections and emerging therapies like laser treatments, offer hope for patients seeking relief from keloid-related symptoms. Continued research into the underlying mechanisms of keloid formation promises further insights and improved therapeutic options, aiming to enhance outcomes and quality of life for those affected.

The pathophysiology of keloid formation remains multimodal and complex. The major categories for treatment can be divided into medical and surgical, alone or in combination, and each treatment offers varying degrees of success graded by time to recurrence. Despite understanding the various risk factors for keloid formation, the lack of animal models limits investigation into the precise mechanism involved. Fibroblasts and myofibroblasts create a collagen-containing extracellular matrix (ECM), which is closely regulated between formation and degradation. An imbalance of collagen production and ECM degradation contributes to aberrant scar formation and has been directly linked with keloid formation. A recent review of treatment modalities by Ekstein and colleagues12 that reviewed over 100 articles demonstrated that surgical excision alone had the highest recurrence rate and brachytherapy following excision had the lowest recurrence rate. Studies have consistently demonstrated the efficacy of radiotherapy; however, it is expensive and only available in large hospital centres, significantly limiting its utility. Furthermore, radiotherapy has long been used as last-line therapy for keloids, as secondary risks of radiation exposure are not insignificant for this population. Intralesional injection of triamcinolone acetonide alone was shown to be the most prevalent treatment for keloids, as it is non-invasive and relatively inexpensive to perform. Increasingly, studies look to assess easy-to-perform and inexpensive treatment modalities, to optimise their efficacy and reduce the rate of recurrence.

Conclusion

We present a technique for the repair of keloids, which minimises the risk of recurrence and improves the aesthetic outcomes for patients. Tensionless closure is vital to the formation of aesthetically pleasing scars, especially in patients prone to keloids where there is excess proliferation of ECM. This technique highlights the importance of this basic surgical tenet by placing the point of maximal tension underneath the incision site and offloading any tension on the wound edges. In combination with a deckled incision, which acts as multiple Z-plasties across the incision line, tension-free closure using the split-dermis technique provides an optimal environment for wound healing. Furthermore, the technique is simple to perform and does not require any special tools or machines, making it a useful adjunct for every plastic surgeon faced with this difficult condition.

Patient consent

Patients/guardians have given informed consent to the publication of images and/or data.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding declaration

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Revised: December 10, 2024 AEST