Introduction

Solitary plasmacytoma is a rare condition of monoclonal plasma cell dyscrasia that often appears as a solitary tumour of bone or soft tissue. It presents in a range of locations in the body. Due to the wide spectrum of sites, it has been reported to mimic several soft tissue and bone pathologies, including osteomyelitis, meningiomas, carcinomas and ameloblastoma. In the following report, we describe a patient with a solitary plasmacytoma of bone (SPB), that mimicked an enchondroma of the left third metacarpal bone.

As this pathology presents in isolation, it may be referred directly to hand surgeons. However, it’s prudent to manage SPB using a multidisciplinary team that includes haematologists and radiation oncologists because, in most circumstances, the primary treatment modality for this tumour is radiotherapy. Additionally, in every case of SPB, clinicians need to exclude systemic multiple myeloma and ensure long-term surveillance is arranged as patients have a high risk of developing systemic disease.

Case

A 35-year-old, otherwise well patient, presented with reduced grip strength in the left hand over a period of a few months. An X-ray revealed a cystic lesion of the third metacarpal suspicious for an enchondroma, with a likely associated, non-displaced pathological fracture that was managed non-operatively. During this period, the patient underwent gentle range of motion exercises and incorporated lifestyle modifications to avoid loading the skeleton. A repeat X-ray six months later showed the cystic third metacarpal lesion with interim growth of roughly 10 mm (Figure 1).

Although both X-rays were reported as an enchondroma by independent consultant radiologists, the interim growth was noted to be unusual. A radiology-guided biopsy was deemed too risky for inducing a fracture; instead the patient had an open curettage and synthetic bone graft under general anaesthesia.

A dorsal approach was used to access the third metacarpal. Intraoperatively, the tumour’s macroscopic appearance resembled a typical enchondroma; however, there were two unusual findings that were not identified on the X-ray. Firstly, there were areas in the third metacarpal with complete cortical erosion and secondly, the tumour had expanded outside the confines of the bone into the adjacent soft tissues. Although there was no fracture, intraoperative findings confirmed that the patient would be at high risk of fracture given the areas of cortical loss and thinning.

The tumour was curetted in the usual fashion for an enchondroma and sent for histology. The remaining defect was packed with synthetic bone substitute and the patient was immobilised in a volar slab, with outpatient follow-up with gentle hand therapy exercises for range of motion.

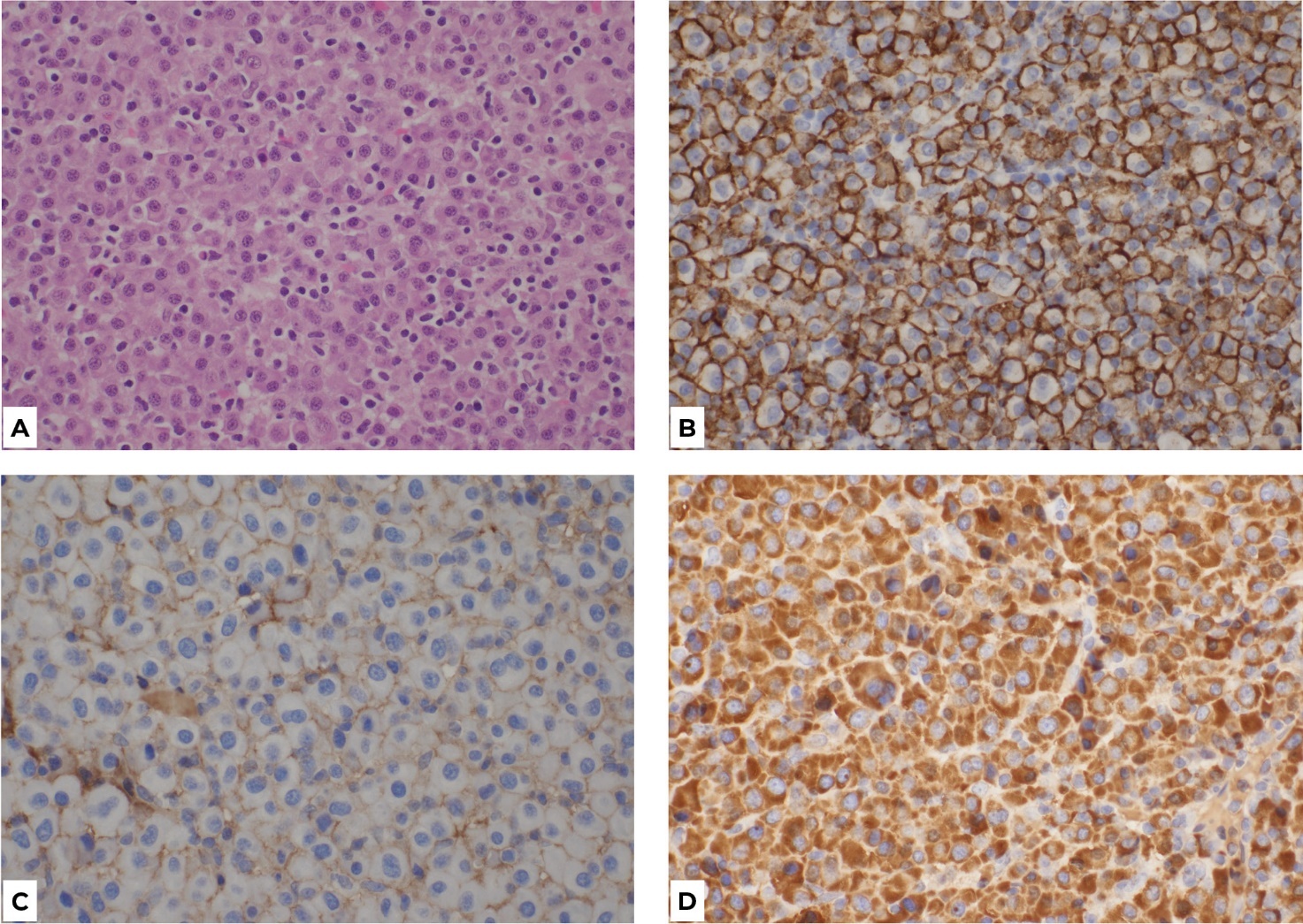

The histology results at the one-week postoperative mark showed the tumour was consistent with plasmacytoma (Figure 2). Given the unexpected diagnosis, the patient was referred to haematology and radiation oncology. He was further investigated with a PET scan, CT skeletal survey, bone marrow aspirate, blood tests and urine tests to exclude multiple myeloma or other haematological malignancies.

Investigations confirmed the diagnosis of a solitary bone plasmacytoma that was positive for Epstein Barr virus (EBV) with no current evidence of multiple myeloma. The patient was discussed at the myeloma multidisciplinary team meeting with a decision to proceed to treatment with radiotherapy, which commenced six weeks postoperatively. The patient had full range of motion six weeks post surgery and returned to full work duties after radiotherapy. He has residual mild weakness that does not affect daily tasks. At the annual review, there was no evidence of recurrence or fracture. The patient remains under oncological surveillance.

Discussion

Solitary plasmacytoma of bone accounts for 70 per cent of monoclonal plasma cell dyscrasias, with the remaining 30 per cent being the extramedullary plasmacytoma that occurs in soft tissues.1 The cumulative incidence of SPB is 0.15/100,000 and it accounts for 5–10 per cent of all plasma cell neoplasms.1,2 Although the aetiology of this disease process remains unknown, trauma as well as certain viral infections such as EBV and hepatitis C have been implicated in its pathogenesis.3 Solitary plasmacytoma of bone should be considered as a differential diagnosis in lytic bone lesions in patients over 30 years of age, especially between the ages of 55–65 when SPB most frequently presents.

Prior to histological assessment, the intraoperative appearance of cortical erosion and tumour expansion outside of the cortical confines raised concerns for the rare diagnosis of enchondroma protuberans. There have been just over 20 case reports of this condition in the literature.4 Enchondroma protuberans is a benign cartilaginous bone tumour that exhibits an exophytic growth pattern outside the cortical confines of the bone and infiltration into soft tissues. Similar to enchondroma, enchondroma protuberans may present with pain, a mass or a pathological fracture and should be considered alongside SPB in the differentials of lytic bone tumours with exophytic growth patterns. It is treated either with a marginal excision or with curettage and bone grafting.4 However, the histological findings in this case were consistent with a plasmacytoma rather than enchondroma protuberans.

The diagnosis of SPB was established for our patient only after systemic disease was excluded, as plasmacytoma may present as a part of multiple myeloma. Certain specialists consider the two conditions to be part of the same disease spectrum, as SPB often progresses onto multiple myeloma. The risk of progression to multiple myeloma is reported as 65–84 per cent in 10 years and 65–100 per cent in 15 years.2 The median progression time to multiple myeloma is two to three years, despite curative therapy. In patients with SPB who progress onto multiple myeloma, the five-year survival rate is 33 per cent.2

The incidence of plasmacytoma in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma patients varies from 3.5–18 per cent.5 Therefore, once a plasmacytoma has been diagnosed on tissue, it is crucial to proceed with patient care in a multidisciplinary setting, using the expertise of haematology and radiation oncology teams. The patient must be screened with whole-body imaging, and have bone marrow, blood and urine tests to exclude multiple myeloma, as the prognosis and treatment for the two conditions vary greatly.

The standard treatment for SBP is radiotherapy alone, with a local control rate of 80 per cent or greater. Surgery can be considered in cases of disease presenting with bony instability or a high risk of fracture, but it should be supplemented with postoperative radiotherapy to minimise the risk of recurrence.2,6 In our patient’s case, surgery was able to provide a tissue diagnosis as all preoperative imaging suggested enchondroma. Additionally, given the areas of cortical erosion, the metacarpal was at high risk of fracture, thus debulking the tumour burden and reinforcing the metacarpal with bone substitute has reduced the risk of an impending fracture. Radiotherapy was also able to commence six weeks postoperatively as recommended in the literature.6

Axial skeletons, such as the skull and vertebra, are the most common locations for SPB.2 It is exceedingly uncommon in the hand, with only three case reports published to the best of our knowledge.3,7,8 There are also case reports of extramedullary plasmacytomas, including one reported as being present in the flexor tendons of the hand.9 In comparison to the published case reports of SPB of the hand, our patient is the only patient to undergo tumour debulking followed by radiotherapy for a hand tumour.3,7,8

Conclusion

This case illustrates the importance of histopathological examination of all resected hand tumours even when they have radiological and intraoperative appearances that are typical of benign hand tumours. In this instance, histopathology findings guided referrals to haematology and radiation oncology for multidisciplinary management to exclude systemic disease, facilitate radiotherapy and link the patient with the most appropriate specialties for long-term surveillance.

Acknowledgements

We thank pathologists Dr James Rickard and Dr Justin du Plessis for their contribution to the pathology slide images and interpretation.

Patient consent

Patients/guardians have given informed consent to the publication of images and/or data.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding declaration

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Revised: April 15, 2024 AEST; March 10, 2025 AEST