Introduction

Cosmetic tourism is a complex issue. The increasing prevalence of cosmetic tourism has been mirrored by an increase in the incidence of atypical infections.1,2 Wentworth and colleagues demonstrated an increase in cutaneous mycobacteria infections over the last 30 years, with a significant proportion occurring after cosmetic surgery (14%) and surgery in general (10%).3 Mycobacterium abscessus is one of the more difficult mycobacteria to treat due to antimicrobial resistance and it can cause significant complications, such as wound dehiscence and substantial scarring.2,4 Diagnoses can be delayed due to low clinical awareness, highlighting the need for vigilance, especially among clinicians treating patients returning from surgery abroad.2

We present a rare case of M abscessus infection following facelift surgery, outline the challenges in diagnosis and management of this organism, and discuss the limitations of evidence in this area.

Case

An otherwise well 64-year-old woman presented to the plastic and reconstructive surgery outpatient clinic with bilateral facial abscesses post-facelift (Figure 1). The initial operation performed in the Philippines in April 2023 was complicated by bleeding, requiring a return to theatre and oral antibiotics. The patient then returned to Australia, where she developed multiple small bilateral facial abscesses one week postoperatively. She completed courses of oral amoxicillin/clavulanic acid prescribed by her general practitioner for several weeks with no improvement, before being referred to the plastic and reconstructive surgery department 10 weeks postoperatively.

On presentation, the patient reported multiple collections that cyclically grew, discharged and then resolved without significant overlying skin changes or systemic features. Aspiration of the right cheek collection identified M abscessus. On subsequent review, several new abscesses had developed and she was admitted for intravenous antibiotics. Contrast CT and MRI scans both demonstrated multiple foci of skin and subcutaneous thickening, with more prominent small, enhancing collections in the right side of the face.

Treatment

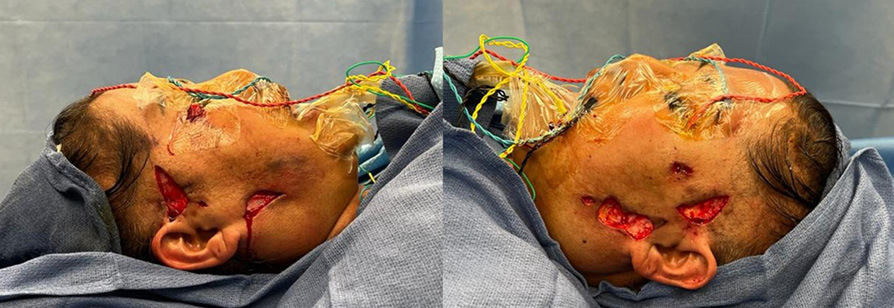

The patient was subsequently transferred to the local tertiary head and neck plastic surgery unit where, after a multidisciplinary review involving infectious disease physicians, radiologists and pathologists, she was booked for emergent surgical debridement. All abscess cavities were debrided to the superficial musculoaponeurotic system and thoroughly washed out with normal saline, hydrogen peroxide and betadine (Figure 2). Frank purulent material was identified in the left cheek only, with chronic granulomatous changes on the right side.

Postoperatively, the patient had daily povidone-iodine packing and was eventually discharged with daily Aquacel (ConvaTec) packing to facilitate healing by secondary intention. This was followed by a prolonged antibiotic course guided by the infectious diseases team. Initially, this involved a broad antimicrobial regimen of amikacin, linezolid, azithromycin and tigecycline. One week post-debridement, this regimen was rationalised to azithromycin, amikacin, clofazimine and linezolid based on interim sensitivities completed at the Victorian Infectious Diseases Reference Laboratory. The ultimate antibiotic regimen, based on finalised sensitivities, was intravenous amikacin continued for six weeks via a PICC line, and ongoing oral azithromycin and clofazimine for six months.

Our patient was discharged home almost two weeks post-debridement and has progressed well in her outpatient reviews with the plastic surgery and infectious disease teams. She healed fully by six weeks postoperatively and was followed up by the infectious diseases team until six months postoperatively with no recurrence.

Discussion

A review of current evidence was conducted using the terms ‘mycobacterium’, ‘mycobacterium abscessus’, ‘plastic surgery’, ‘facelift’ and ‘cosmetic’ in the Ovid MEDLINE database from inception to September 2023. Overall, 41 papers were retrieved. Twenty were excluded as these studies were not related to cosmetic surgery (n = 1), not related to M abscessus (n = 3), focused on genomics or antibiotic selection only (n = 5), not in English (n = 5), were reviews (n = 3) or letters/brief reports (n = 3). A further nine papers were included from searching reference lists, for a total of 30 papers. Among these, data for 87 patients only were presented in case reports or series. There is a distinct paucity of literature on management and patient outcomes in relation to these infections.

While Mycobacterium infections are rare, they represent a significant infective process for the patient that is often underappreciated.5 This case highlights several key points in the returning cosmetic tourist surgical patient—increasing incidence of atypical infections, diagnostic challenges coupled with low clinical suspicion and management complexity. Mycobacteria are mostly considered to be rare and slow-growing, but there are classes of rapidly-growing nontuberculous mycobacteria that are often associated with multidrug resistances, including M abscessus. The most common mycobacterial infection following cosmetic procedures is M abscessus.6 It is well established that these mycobacteria are commonly found in contaminated water sources, with several studies demonstrating resistance to standard disinfectants and associations with improperly sterilised surgical equipment or contaminated skin-marking pens.2,7,8

Epidemiological studies have demonstrated an increasing prevalence of mycobacterial infections, mirroring the rise in cosmetic procedures over the last 30 years.2,3 As such, it is important for clinicians to recognise that what may previously have been considered a rare and atypical presentation is becoming more common.

Mycobacterium abscessus infections are considered difficult to manage for multiple reasons, including their rapid growth and resistance to antibiotics, antiseptics, biocides, sterilising agents and disinfectants.5 Treatment will consist of a combination of antibiotics (macrolides, cefoxitin, amikacin, imipenem) and surgical excision for deeper infections.9,10 Nevertheless, the high virulence and rapid growth of M abscessus contribute to multidrug resistance. Adequate tissue specimen collection is vital, as previous empiric therapy can stagnate culture growth.11 Early involvement with the infectious diseases team facilitates DNA sequencing using the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and homology comparisons, which are considered the best methods for organism identification, susceptibility testing and evaluation of inducible macrolide resistance in erm genes with antibiotic use.10 Often, M abscessus infections are mistaken for more common bacterial infections, such as Staphylococcus or Streptococcus species, and mismanaged for a period prior to recognition.2 The delay between inoculation, onset of symptoms and subsequent diagnosis can result in significant tissue damage, antibiotic resistance, worse cosmetic outcomes and psychological distress.2

Mycobacterial infections traditionally present with multiple subcutaneous abscesses at the surgical site, and the persistence of infection, despite empiric antibiotics or debridement, is an important clinical feature suggestive of mycobacterial infection.2 They can also spread to cause significant soft tissue damage, including tenosynovitis, myositis, osteomyelitis and septic arthritis.9 Early identification of these infections is vital for local control and prevention of significant tissue necrosis.

In these situations, careful counselling of patients is required to address some of the central issues of cosmetic tourism. Patients with cosmetic tourism complications often have no recourse to legal proceedings or the practical ability to address the root source of the adverse event,8 and may face an increased financial burden as a consequence.4 A study of patients in the United States with cosmetic-surgery-related M abscessus infections also found that a majority of patients (62%) had heard of the clinic they sought care at through their community, leading to social impacts as well.4

Early identification, multidisciplinary strategies (including early involvement of infectious disease teams), surgical debridement and long-term antibiotics, are essential in the management of these infections.6 Awareness and high clinical suspicion of these infections, particularly in returned cosmetic tourism patients, can facilitate early detection of atypical pathogens, which is imperative for successful management.

Conclusion

This case underscores the importance of heightened clinical awareness for M abscessus infections, especially in light of the well-documented, increasing trend for cosmetic tourism, and the prevalence of rapidly-growing Mycobacterium. Early identification, multidisciplinary collaboration, and appropriate surgical and long-term antibiotic therapy are key to managing these complex infections. We present this case as a reminder to clinicians to be proactive in screening for atypical pathogens in appropriate cases, as early intervention can mitigate the risk of severe complications.

Patient consent

Patients/guardians have given informed consent to the publication of images and/or data.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding declaration

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Revised: January 27, 2025 AEST