Introduction

Venous malformations (VMs) are low-flow lesions that affect about 1 in 2000 individuals.1 Most sporadic cases are now known to be caused by somatic mutations in the TEK or PIK3CA genes.2 Clinical signs of VMs include a bluish-purple swelling or mass that is soft and compressible, occasionally with palpable phleboliths and spontaneous thrombi. They may be painful or episodically tender and can involve superficial or deep structures. Enlargement can occur with use of the Valsalva manoeuvre or during puberty or pregnancy. Any tissue or organ can be affected, including bone and the orbit.3 Intramuscular VMs may not show any clinical signs until they become painful or there is a complication. Duplex ultrasound with colour Doppler is the first line of investigation. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the preferred second-line imaging investigation, due to its superior soft tissue contrast resolution and multiplanar capabilities.4 Computed tomography (CT) has a limited role in evaluating VMs due to its poor soft tissue contrast resolution and use of ionising radiation. Radiographs are also of limited use, although the presence of phleboliths in a paediatric patient is highly suggestive of a VM.5,6

Localised lesions can be treated with surgery, while diffuse lesions are treated by sclerotherapy, using agents such as ethanol, bleomycin, sodium tetradecyl sulfate and polidocanol.7 Occasionally, interventional radiology may be used prior to subsequent surgery. Medical treatments, including sirolimus and targeted therapies such as the PI3K inhibitor alpelisib, are being increasingly used. Surgical debridement, exploration and partial resection are the likely outcomes from a misdiagnosis of necrotising soft tissue infection, rather than infected and/or thrombosed VM. Here we present two cases that exemplify this clinical issue.

Case 1

A previously well six-year-old male presented to the emergency department with a two-day history of increasing right thigh pain and fever. The parents reported that there had been a blue mark on the hip from birth. At around age two there had been two episodes of pain and swelling in the area with a fever of 38°C which resolved. One month prior to admission, the patient developed pain which progressively worsened. He refused to weight bear and had worsening thigh swelling and erythema. He had no other systemic or constitutional symptoms and no history of travel or contact with sick people.

On examination, the patient looked unwell with a temperature of 39.6°C and tachycardia. There was some purpuric discolouration on the right thigh, with notable swelling and erythema. Although the compartments of the thigh and calf were soft, the patient refused to move or be touched. No crepitation or collection was palpable.

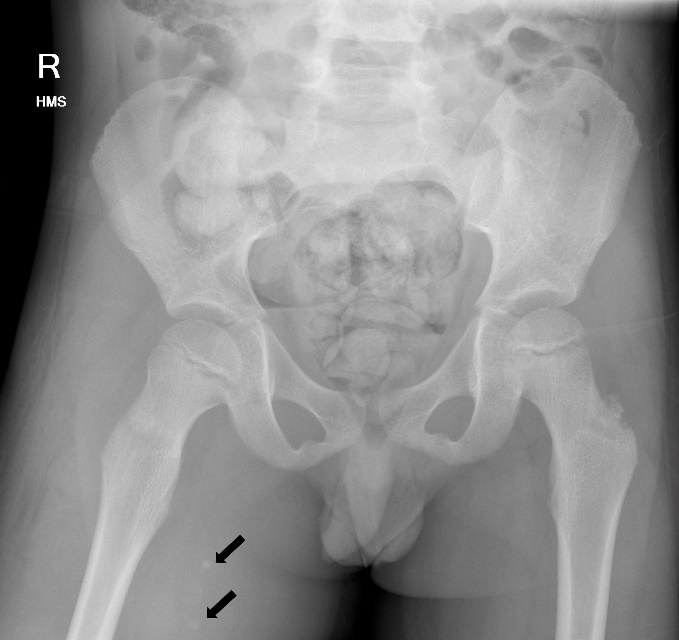

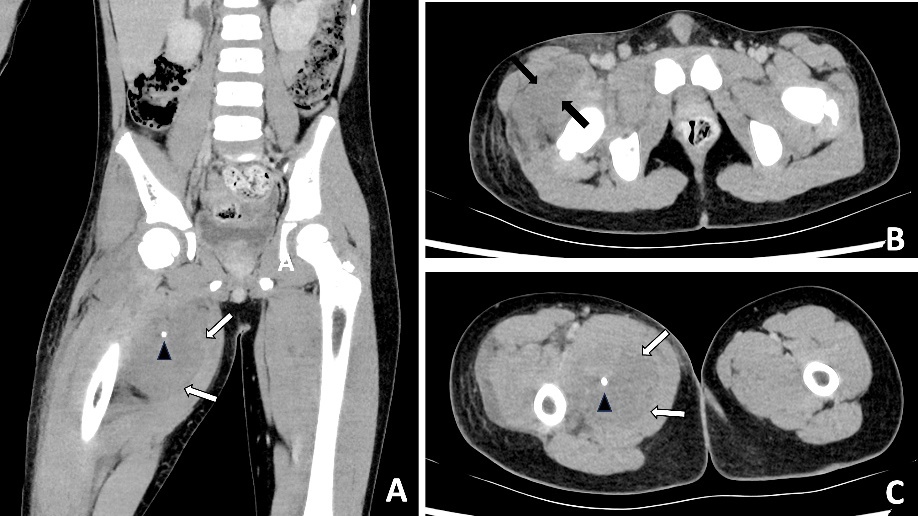

Blood results revealed a high white blood cell count (30.3 × 109/L) with neutrophilia and high C-reactive protein (245.2 mg/L). An X-ray of the hip was performed and interpreted as normal, although in retrospect, phleboliths were present in the region of the adductor muscles (Figure 1). Abdominal CT was normal. Fat stranding, soft tissue swelling and possible fluid collections were identified within the anterior and medial thigh on CT. Retrospectively, there were also multiple intramuscular phleboliths within the adductor muscles (Figure 2).

Many differential diagnoses including necrotising soft tissue infection or abscess were considered. The patient was transferred to the operating theatre for exploration and washout. Intraoperatively, there was no pus or clinical appearance of necrotising fasciitis. However, it was noted that there were multiple inflamed intramuscular venous lakes, consistent with VMs. A conservative sampling biopsy of the lesion was taken for postoperative confirmation of the diagnosis of VM. The nearest dedicated children’s hospital with subspecialist expertise in VMs was contacted for advice regarding ongoing management.

The patient remained febrile until day four post washout. Histopathology was inconclusive and a further sample was recommended if clinical uncertainty remained. An MRI performed one week following the initial presentation demonstrated a trans-spatial low-flow VM within the anterior and medial compartments of the thigh. On post-contrast T2 images, there were two thick-walled peripherally-enhancing fluid collections that were interpreted as infected collections (pyomyositis).

On day seven post surgery there was wound dehiscence and discharge at the incision site. Repeat washouts were performed on day nine and day 15. There was no pus intraoperative, however, there was significant soft tissue swelling in both washouts. The first intraoperative microbiology culture grew Streptococcus pyogenes; subsequent cultures were negative. The infectious disease team recommended six weeks of amoxicillin following the final washout. Following resolution of the acute episode, the patient was referred to a tertiary centre with subspecialty experience in managing paediatric VMs. At eight months follow-up symptoms had largely resolved. He was reassessed for potential sclerotherapy, but although there was some residual lesion on MRI this was not visible on ultrasound, so sclerotherapy was not performed.

Case 2

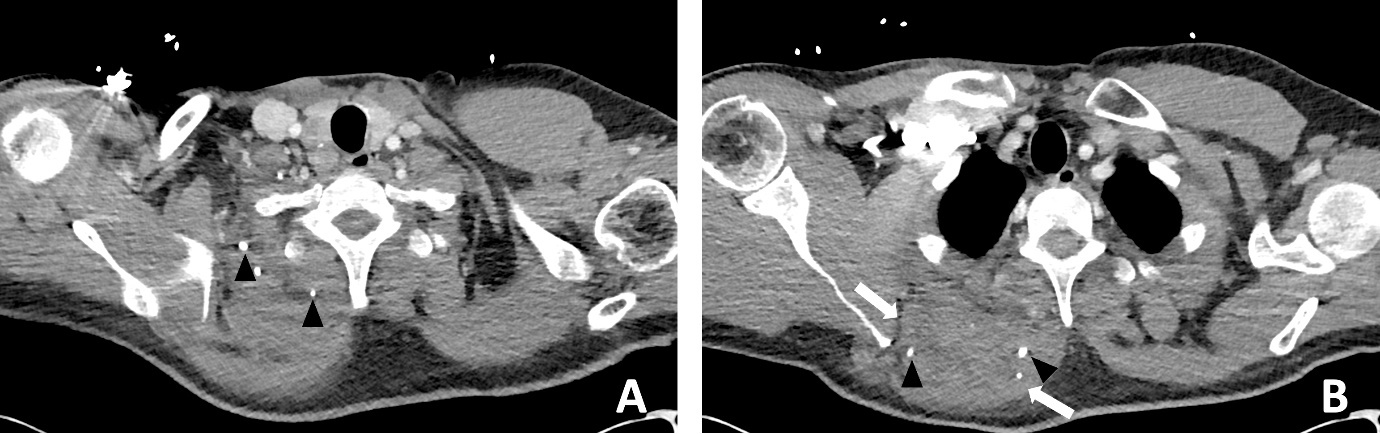

A previously well 47-year-old male presented to the emergency department with worsening atraumatic right shoulder pain and malaise. He was septic with a white blood cell count of 13.4 × 109/L and C-reactive protein of 489 mg/L. A chest CT reported a ‘large ill-defined heterogeneous density mass lesion within the upper medial posterior chest…with small volume fluid and subcutaneous fat stranding’. Internal hyperdense foci were interpreted as calcification or possible foreign bodies (Figure 3). The patient was admitted to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) and placed on vasopressors support. The plastic surgery team was consulted to provide an opinion on urgent surgical management.

The patient was suspected to have either a rhomboid abscess or necrotising soft tissue infection and was transferred to surgery. Intraoperatively, there was turbid blood-stained fluid in locules within the rhomboid muscles, potentially consistent with an infected VM. An attempt was made to determine the border of the lesion in the rhomboid, in the hope that it could be resected completely without significant morbidity, but the lesion extended into the surrounding tissues and muscles. Histology favoured VM and microbiology from washout showed S pyogenes.

The patient returned to ICU postoperatively for management of septic shock with multi-organ failure (hypotension, hypoxia and acute kidney injury). His blood culture subsequently grew S pyogenes. Clindamycin, intravenous gamma globulin and benzylpenicillin were administered, as per the infectious diseases team.

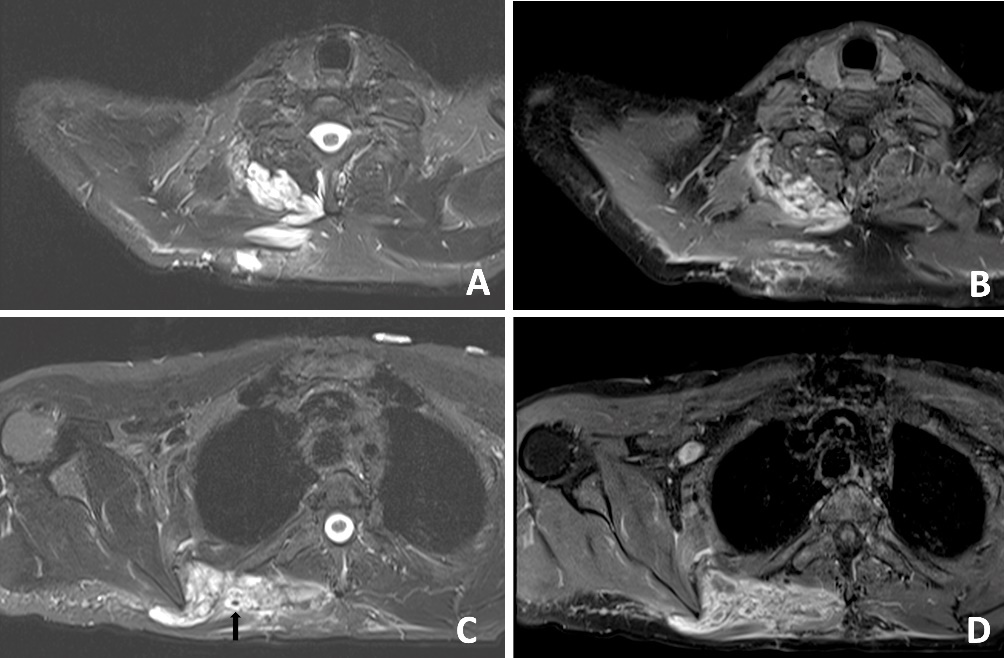

A subsequent washout was performed on day three; intraoperative findings were similar to the first operation. The patient’s fever subsequently settled. An MRI was performed on day 11 to evaluate for possible VM or sarcoma. An MRI revealed a ‘trans-spatial right paraspinal mass involving the trapezius and rhomboid muscles with internal phleboliths, no fluid levels or flow voids, in keeping with a slow flow vascular malformation’ (Figure 4).

The patient was discharged on day 11 and referred for subspecialist review in a tertiary hospital VM clinic. Sclerotherapy was considered, but after discussing the risks versus benefits, it was decided to continue monitoring the lesion. The patient continued to have regular follow-up for four years post initial presentation. He remains well and has not had another acute episode.

Discussion

The two cases above emphasise the risk that infected VMs in acutely unwell patients can be misdiagnosed in the emergent setting as possible necrotising soft tissue infections, due to the very unusual nature of the soft tissue changes on CT scanning. Together, the cases demonstrate that the first presentation of infected VMs can occur at any age and that VMs may present for the first time with potentially life-threatening infection and clinical sepsis.

There have been four reported paediatric cases of infected intramuscular VMs presenting emergently (two 5-year-olds, one 2-year-old and one 10-month-old).8–11 So far, there is very limited data on the pathophysiology behind infection of intramuscular VMs. This appears to be the first case series on this topic.

These two cases raise questions about how the management of similar cases can be improved in the future, as both patients were subjected to urgent surgery with the suspicion of necrotising soft tissue infection. The surgery performed helped rule out potentially life-threatening necrotising fasciitis and permitted direct visualisation of the VM for diagnosis. Samples were taken for microscopy, culture and sensitivity, in addition to histopathology, to confirm the nature of the underlying pathology. Surgery may play an important role in treating a necrotising soft tissue infection but ideally should not be part of investigations for an infected VM. Further expert advice was sought in both cases to help direct ongoing acute care and ongoing management following recovery.

It is important to keep in mind the potential differential diagnosis of infected VM when presented with a similar clinical presentation. Table 1 compares the characteristics of necrotising myositis and infected intramuscular VMs.12,13 If possible, the diagnosis of infected VM should be made with appropriate history, examination and routine imaging (radiographs, ultrasound or CT). The definitive mode of imaging, MRI, is not typically used in an unstable patient in the emergent setting.13

In retrospect, the presence of intramuscular phleboliths on CT in the cases presented above was the best clue to the diagnosis of an infected VM. Phleboliths occur in approximately 30 per cent of VMs.15 Intramuscular phleboliths have a limited imaging differential diagnosis and are generally taken to be pathognomic of VM.16 Radiologist and clinician awareness of this rare presentation of VMs is important; if intramuscular phleboliths are identified, the diagnosis of VM should be raised and the use of MRI may further assist in the diagnosis. If clinical doubt remains in an acutely unwell patient, prompt surgery to exclude necrotising soft tissue infection is prudent.

Conclusion

Timely surgical exploration is indicated in septic patients where necrotising soft tissue infection cannot be excluded. However, it is important to consider rare conditions that may present similarly, such as infected VMs. The presence of intramuscular phleboliths on CT, especially in a child, is the best imaging clue to this unusual diagnosis and should not be overlooked.

Patient consent

Patients/guardians have given informed consent to the publication of images and/or data.

Conflict of interest

Anthony Penington receives project grant funding from the Medical Research Future Fund and is a consultant for Novartis. Michael Findlay is a paid advisor for Becton Dickinson. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose with regard to the research described in this article.

Funding declaration

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Revised: May 1, 2025 AEST