Background

Women with a family history of breast cancer and/or a predisposition to breast cancer from a mutation in particular genes have an elevated risk of developing breast cancer. Approximately 5–10 per cent of breast cancers are due to germline mutations,1 most commonly in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes.2,3 These mutations were first discovered in the mid-1990s.4,5 Since then, several other high-risk, but less common, breast cancer germline mutations have been identified, along with moderate- and low-risk mutations.3,6

One option to manage the elevated risk of breast cancer is risk-reducing bilateral mastectomy (RRBM), which reduces the risk by at least 95 per cent.7–9 This benefit applies across all age ranges of BRCA mutation carriers. In 2014, Cancer Australia cited the average cumulative risk of developing breast cancer by age 70 years at 57 per cent (80% by age 80) for women with a BRCA1 mutation and 49 per cent by age 70 (88% by age 80) for women with a BRCA2 mutation.1 This compares with a 14 per cent lifetime risk for women without a BRCA mutation in Australia.10 The latest Canadian study from Metcalfe and colleagues, published in 2023, concluded that women with BRCA pathogenic variants ‘have a high risk of cancer between the ages of 50 and 75 years and should be counselled appropriately’.11(p902)

In addition to a higher incidence of breast cancer, BRCA1/2 mutation carriers develop breast cancer earlier than non-carriers and tend to have more aggressive disease. Over half of women (57%) with BRCA1 mutations and a quarter of women (28%) with BRCA2 mutations are diagnosed with breast cancer before the age of 50 years.2 In comparison, less than 25 per cent of non-BRCA mutation carriers in Australia are diagnosed below the age of 50.12

Another advantage of RRBM is detecting existing occult breast cancers that otherwise may have been diagnosed at a more advanced stage. Metcalfe and colleagues conducted a large, prospective, pseudo-randomised study with BRCA mutation carriers, published in 2024.13 Having found 15 occult cancers at the time of RRBM, the authors reported that none of these women had died during follow-up. They concluded that RRBM had prevented 80 cancers and potentially another 15 breast-cancer-related deaths, through removal of these occult cancers.13

No international guidelines specify target waiting times for RRBM. Guidelines from the USA’s National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN),14 Cancer Australia1 and the UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)15 recommend that all women at high-risk should be offered a discussion about RRBM.

This systematic review has two aims: the primary aim is to document international data on uptake and predictors of RRBM and time between identification of high-risk status and RRBM; the secondary aim is to explore barriers to timely surgery.

Methods

Selection criteria

Inclusion criteria:

-

studies that present data of unaffected women (without a personal history of breast cancer) who have tested positive to BRCA1/2 genetic mutations or have otherwise been defined as ‘high-risk’

-

studies that define the time period to RRBM (with or without breast reconstruction)

-

quantitative studies with original data

-

studies published in English between 1996 and March 2024.

Exclusion criteria:

-

studies with no original data (eg, systematic reviews, editorials, commentaries)

-

studies that do not define ‘time to surgery’

-

studies that report fewer than 10 unaffected women who have RRBM

-

studies about men with breast cancer.

Definition of high risk

We have defined ‘high-risk’ women as those with a 30 per cent or higher risk of developing breast cancer in their lifetime, which corresponds to the NICE familial breast cancer guidance.15 These high-risk women have an 8 per cent or greater chance of developing breast cancer between the ages of 40 and 50. All women who have a pathogenic mutation in the BRCA1, BRCA2 or TP53 genes are defined as high risk using this criterion.15

Literature search

Four electronic bibliographic databases were systematically searched between 16 February and 1 March 2024: MEDLINE, EMBASE, Scopus and PsycINFO. The search strategies included studies published from 1 January 1996 (because BRCA1/2 mutation screening became available for clinical use in 1996).16 One author (KD) worked with a research librarian at the University of Sydney, to develop the search criteria. Detailed information on the search terms and results is available in Supplementary material 1.

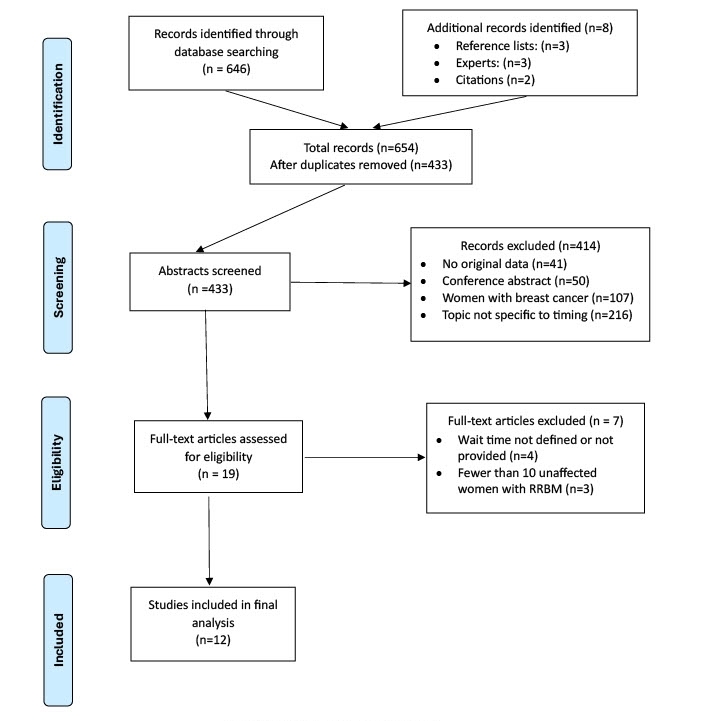

All abstracts identified in the searches were exported to an EndNote (version 21, Clarivate) library. Two authors (KD and MB) independently reviewed 433 abstracts. When exclusion criteria were applied and duplicates removed, this left a total of 206 abstracts for further review. Reference lists of each included article were searched and citation searching was also conducted to identify other relevant publications. Co-authors were consulted for additional relevant articles. Following this comprehensive review process, selection differences between reviewers were discussed and a consensus list developed. Nineteen articles underwent full-text review by KD and MB, with 12 of these meeting the selection criteria. The selection process is outlined in Figure 1. The methodology followed the PRISMA 2020 reporting guidelines for systematic reviews.17 Grey literature included Australian1 and international guidelines.14,15 Ethics approval was not required for this systematic review of secondary data.

Data analysis

Relevant data were extracted from the 12 included studies and summarised in two tables. Table 1 contains the characteristics of included studies, comprising first author, year and location of publication, data source and study aim, population, setting, study design, time frame and study outcomes. Table 2 provides information on the main findings relating to uptake rates, timing and predictors of RRBM.

Results

This systematic review has demonstrated a wide range of median waiting times from genetic testing and/or disclosure to RRBM across 12 studies, comprising 9851 unaffected high-risk women. Furthermore, there tended to be wide variation around the median time within most studies. Only one study included information on specific waiting time from a woman’s decision to have RRBM to surgery.26

All included articles were observational cohort studies, comprising data audit/review over varying periods of time. Within-study comparisons were made between women at different risk levels, age ranges, BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation carrier status, or familial high-risk. One study used regularly administered questionnaires in addition to the data review.24 Six articles were published between 2007 and 2012,19,20,23,24,28,29 and six between 2015 and 2023.21,22,25–27,30 Three articles were based on the same English dataset, at different timepoints and with different data subsets.20,21,27 We have assumed participant overlap between these publications which contributed 7195 (73%) of the total systematic review patients. Two studies were based in the USA19,22 and two in France,24,29 while one study came from each of the following countries: North America and Europe combined,23 Slovenia,25 Canada,26 Denmark28 and the Czech Republic.30 Four of the 12 studies were fully prospective,21,23,24,27 with one using both retrospective and prospective data collection.29

Primary aim: rate of RRBM uptake

Reporting of uptake figures varied across studies. Some included uptake by gene mutation/risk level,21–23,25 individual centres,23 age,25,27,30 or RRBM with or without breast reconstruction,26 and others considered whether participants had RRBM only or also had risk-reducing bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (RRBSO).24,25,30 Overall, for RRBM only, uptake ranged from 3.6 per cent with medium follow-up of 2.33 years,24 to 50 per cent with 10-year follow-up.28

Primary aim: predictors of RRBM

Table 2 provides information on factors found to be independently and significantly associated with RRBM uptake. Findings about age and RRBM varied. One study reported age was not associated with RRBM uptake,22 one found a decreased association in women aged over 5021 while another reported an increased association for women aged under 60.19 Results reported at two-year follow-up stated women in their 50s had a lower RRBM uptake rate than women aged in their 30s.27 Several other studies supported the finding that uptake was highest in women aged between 30 and 45 years of age, with a median/mean age around 40.20,23,24,27

Primary aim: time to RRBM surgery

Seven of the 12 studies defined time to RRBM as the time from disclosure of a positive genetic mutation test result to date of RRBM (see Table 2).19,24–29 Overall, median time to RRBM ranged from five months19 to 92 months.28 Julian-Reynier and colleagues found the time to surgery was shorter when the psychological impact of BRCA1/2 result disclosure was stated to be higher and when the patient had made the decision pre-testing.24 Macadam and colleagues reported Canadian data from 333 women using three different time spans and 40 per cent of these patients made the decision to proceed within three months of mutation disclosure.26

Secondary aim: to explore barriers to timely surgery

Barriers to accessing timely RRBM were specifically identified in two studies. This and colleagues noted that in France, guidelines recommend women considering RRBM undergo a mandatory psycho-oncology consultation prior to surgery, which is organised for them, followed by a four-month period of reflection before they undertake RRBM.29 The authors commented that such attitudes towards a woman’s ability to make her own informed decision ‘probably partially explains why so few patients in our cohort [5.3%]’ have chosen RRBM.29(p479) The role of clinician attitudes was also raised by Evans and colleagues, who stated that international differences in RRBM uptake are likely to reflect ‘not only cultural differences, but also clinician attitudes and potentially the way in which [RRBM] is discussed, if at all, as a preventative option’.21(p50)

Discussion

This systematic review has demonstrated a wide range of median waiting times from disclosure of genetic testing results to RRBM across 12 studies, comprising 9851 unaffected high-risk women. Furthermore, there tended to be wide variation around the median time within most studies. Only one study included specific information on the waiting time from a woman’s decision to have RRBM to the actual surgery and on the reasons for choice of treatment.26 Such information is important for two reasons: first, there is growing anecdotal evidence from Australia that delay following decision-making can lead to poorer psychological and oncological outcomes for this relatively small number of high-risk women31; and second, uptake rates of RRBM are rising over time.19,22,25,27,30 A 2023 review of UK guidelines for risk-reducing surgery noted the role of RRBM ‘has become widely accepted, and rates have increased in recent years, due to improved genetic testing and significant media attention with consequent increased awareness’.32(p385)

McCarthy and colleagues also commented that because NICE guidelines take several years to develop, guidance for the management of healthy carriers of germline mutations, including risk-reducing surgery, may not be keeping pace with advances in testing.32 Macadam and colleagues commented on the lack of studies that considered the proportion of breast cancers that develop while women who have made the decision to have RRBM wait for surgery.26 They reported five cancers had developed in this time in their patient cohort, with a further three found at surgery (6% of the total RRBM/immediate breast reconstruction group), but noted in all cases that the decision-making component was the main reason for the delay.26

A highly influential decision analysis published in 1997 concluded the benefit received from RRBM declined with age, with little gain obtained after the age of 60.33 More recent studies do not support this decrease in the likelihood of breast cancer with increasing age.1,11 Three studies included in this review provided further support for the need for all BRCA+ women, regardless of their age, to be informed about both surveillance and surgical options. This noted ‘BRCA 1/2-related tumors, especially BRCA1, often occur in young women and are generally triple-negative, and these features are independent predictors of poor outcome’.29(p480) In contrast, Beattie and colleagues reported BRCA carriers aged 60 years and over were least likely to choose RRBM or RRBSO ‘despite their high and increasing risks for breast and ovarian cancers with age’.19(p55) They concluded that discussions about surgical options for gene mutation carriers should include women over 60 years of age.19 Similarly, Ložar and colleagues stated BRCA1 carriers had an estimated lifetime risk of breast cancer of 60–65 per cent by age 70, and 72 per cent by age 80, while BRCA2 carriers’ estimated risk of breast cancer was 45–55 per cent by age 70, and 69 per cent by age 80.25

International differences in RRBM uptake are likely to reflect cultural differences. In Denmark, where 50 per cent of unaffected carriers chose RRBM, risk-reducing surgeries are widely acceptable.28 In contrast, Israel has only a 13 per cent uptake of RRBM.34 The Laitman and colleagues study reported that, even with physician recommendation for RRBM, only 18.5 per cent (20 of 108 cancer-free carriers) opted for RRBM.34 This is despite the higher frequency of BRCA1/2 mutations in the Israeli population than in almost all other countries, and the formation of a not-for-profit organisation to support BRCA1/2 carriers, which encourages them, among other things, to ‘actively pursue risk-reducing surgery’.34(p70) The authors did not explain this finding.

Several barriers to prompt access to RRBM were identified in the results section. In addition, Head and colleagues noted that in Canada, national cancer databases do not collect information on healthy women without breast cancer, making it difficult to accurately assess RRBM trends.35 This is presumably true in most countries, with Denmark being a notable exception.28 Although Denmark had the highest known uptake of RRBM, it also has the longest median time to RRBM (92 months), although 11 per cent had RRBM within six months of receiving their test result.28

The link between pre-genetic testing intentions and the subsequent choice of risk management options, identified by Julian-Reynier and colleagues,24 is supported by a 2010 Dutch study which compared risk management preferences of individual women shortly after genetic test disclosure and matched this with choice of RRBM or surveillance around two years later.36 They found that almost all BRCA mutation carriers follow their first preference for breast cancer surveillance or risk-reducing mastectomy and reported strong predictors for RRBM within two years as younger age and prior preference for mastectomy (R2 = 0.57). Strong attendance at an educational support group made adherence to their original intention more likely (OR 4.8, p = 0.04).36 The stability of women’s preferences was discussed in another Dutch study by van Dijk and colleagues, who reported that 90 per cent of 338 women who opted for BRCA testing had already indicated a preference regarding risk management at baseline and, for most women, these preferences remained stable.37

The study by Julian-Reynier and colleagues also highlighted a crucial factor in determining RRBM uptake rates, that is, the importance of long-term follow-up. They noted that even when women were undecided or opposed to RRBM, a ‘nonnegligible proportion of the women opted for surgery in the long run’.24(p805) Evans and colleagues also found that uptake of RRBM continued to rise up to 20 years from initial risk assessment.21 A report on 24 years of follow-up of the same prospective, large-scale cohort confirmed that while around 50 per cent of RRBM is undertaken within the first two years, later uptake may be driven by several factors.27 These include previously identified issues such as false positive screens, new breast cancer diagnoses in the family or breast cancer-related deaths.20

Three studies have suggested alterations to surgical coordination and timetabling to provide a rapid access model of care. Macadam and colleagues proposed unaffected carriers who have made the decision to proceed with RRBM should be ‘clearly prioritized on a surgeon wait list for consultation and surgery with a guaranteed maximum wait program for the delivery of service’.26(p712) They also suggested a dedicated block of operative time should be allocated to allow surgical oncology and plastic surgery specialists to coordinate RRBM and reconstruction concurrently in adjacent operating theatres.26 A similar approach trialled in an Australian hospital in 2024 was found to significantly increase the number of high-risk gene carriers’ risk-reducing procedures (5–26%, p = 0.001), although waiting time for RRBM did not significantly change (and actually increased) after the intervention (55.0 to 61.1 weeks, p = 1.000).38 An earlier, smaller Canadian study by Head and colleagues developed a rapid access risk-reducing mastectomy and immediate reconstruction (RAPMIR) program, which involved RRBM patients having a separate waiting list to women with breast cancer.35 Although mean wait time from referral to surgery for RAPMIR patients was significantly shorter than for the traditional model (165.4 vs 309.2 days, p = 0.027), women still waited over five months for RRBM.35

Strengths and limitations

This systematic review has several important strengths. The methodology was rigorous, and followed the PRISMA 2020 reporting guidelines for systematic reviews (Supplementary material 2). Reviewed studies covered almost 10,000 women from Europe, Scandinavia, the USA and Canada. Great care was taken to ensure that the findings from included studies were only cited in relation to breast cancer and RRBM; data relevant to ovarian cancer and RRBSO were excluded. However, choice of RRBSO was shown to influence the choice of RRBM in some studies and this may be a confounder.

The main limitation reflects the observational methods used within the included studies. Only four of the 12 reviewed studies were fully prospective, which is considered a superior methodology because inclusion of all relevant variables can be planned, accurately measured and recorded.39 However, an advantage of retrospective studies is that they may have larger, established databases to draw data from. Other limitations include potential selection bias from observational cohort studies on uptake and efficacy of risk-reducing surgeries,40 and the relatively short length of follow-up of most study cohorts, which did not allow for the calculation of accurate RRBM uptake rates over time.21,24,28 Other limitations, due to non-reporting in most publications, include whether RRBM was always discussed or encouraged as an option for newly-diagnosed BRCA mutation carriers,21 and how long women took to make a decision for or against RRBM following genetic testing disclosure.26

Conclusion

There appears to be no clear international or national models that have successfully shortened the waiting time to access RRBM for women who have chosen that option. Furthermore, the literature has documented cases of breast cancer developing while women are waiting for this surgery26 and the case study evidence on the adverse psychological impact of waiting time continues to grow.31

In Australia, surgical wait time is also impacted by choice of breast reconstruction, with the wait often shortest for simple mastectomy without reconstruction and longest for mastectomy with autologous reconstruction. This latter option requires longer theatre times and coordination between breast oncoplastic and plastic reconstructive surgeons, often leading to scheduling delays. Unfortunately, reliable, quantitative data on the time between decision-making and RRBM is lacking for this cohort of women. The creation of a prospective, national and publicly accessible database for women with genetic predispositions for breast cancer would represent an important first step in this process.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge Ms Bernadette Carr, research services librarian at The University of Sydney, for her assistance with the literature search framework, and Dr Nicola Dean and Dr Michael Field for their comments on earlier drafts of this manuscript.

Conflict of interest

Kylie Snook is a member of the Medical Advisory Committee at Inherited Cancers Australia. Melanie Walker receives consulting fees from Exact Sciences. Exact Sciences had no involvement in the preparation of this paper or its submission for publication. Melanie Walker is the Chair/President of the Society of Breast Surgeons of Australia and New Zealand (BreastSurgANZ). The other authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose with regard to the research described in this article.

Funding declaration

Kathy Dempsey received funding from Breast Cancer Network Australia to conduct this review. The other authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Revised: August 5, 2025 AEST