Introduction

Clefts of the lip and palate create problems in feeding, speech, hearing, dental development and facial growth. Despite surgical and multidisciplinary advances in cleft care, associated speech difficulties and facial appearance represent serious barriers to social integration. As a consequence of the multifaceted nature of the condition, there are numerous decisions with respect to the possible clinical, surgical, audiological, orthodontic and speech interventions that have to be made at different times extending from the birth of the child to adolescence and beyond. For certain individuals, the specific intervention chosen at a given time may be non-controversial and firmly evidence-based, whereas at other times there may be options available that have not yet been rigorously evaluated. In general, there is a paucity of evidence from RCTs for many aspects of the management choices to be made for patients with cleft lip and palate. Indeed Berkowitz argues,1 in the context of the use of nasoalveolar moulding, for rigorous evaluation, as did Lee2 much earlier in the wider setting of cleft lip and palate patients.

Despite the plethora of potential questions arising from the complexities of care in patients with cleft lip and palate, a review by Hardwicke and colleagues3 identified only 62 published RCTs from 1 January 2004 to 31 December 2013. Among the 62 RCTs identified, only 10 concerned surgical techniques, with a median trial size of 86 (range 47–376). The largest of these, with 467 infants, was conducted by Williams and colleagues,4 who compared two different lip repairs with two types of palate repair conducted at two different ages in a so-called factorial design. Lu and colleagues5 commented on the advantages and difficulties associated with this design. The other RCT that evaluated repair at different ages was that of Ysunza and colleagues6 who compared results following surgery at two different ages in 76 infants.

We review information from the RCTs concerning palatal surgery at different ages in infants and discuss some of the logistical and statistical problems associated with the design and conduct of such trials. For the purpose of this article, we focus on speech outcomes with respect to VPC. Finally, we propose a format for an international multicentre trial of a very flexible design to investigate the appropriate timing of surgery in this context.

Method

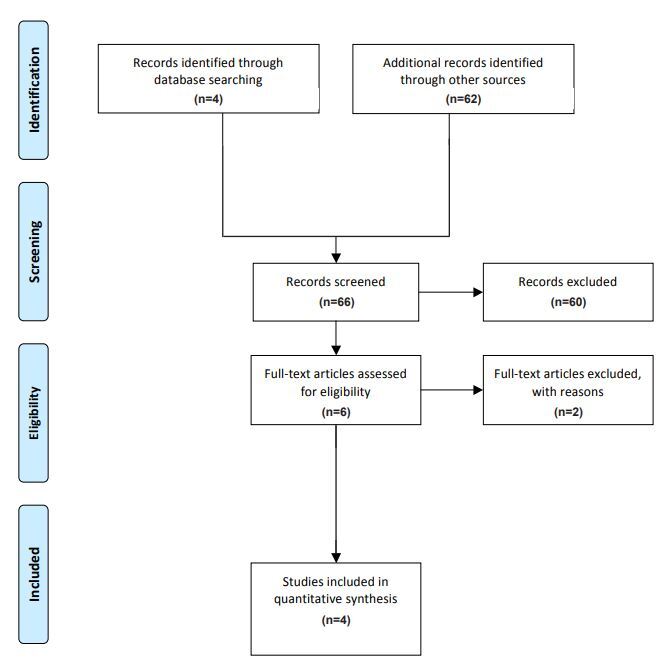

A 2017 review by Hardwicke and colleagues3 listed all the RCTs conducted in cleft lip and palate over a 10-year period from 1 January 2004 to 31 December 2013 in English using the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, MEDLINE® and EMBASE with key words ‘cleft lip’ or ‘cleft palate’. From this review we were able to identify two RCTs that compared different ages at the time of surgery.4,6 A literature search from 1 January 2014 to 29 February 2020 identified four further RCTs, two of which compare surgical timings.7,8 Surgical timings investigated by Shaffer and colleagues9 describe a retrospective (hence non-randomised) study of the experience from a single craniofacial clinic and was excluded. A survey by Slator and colleagues of 18 cleft centres in the United Kingdom concluded ‘there remains considerable variation in both the sequence and timing of surgical repair of cleft lip and palate in infancy’ and was also excluded.10 See Figure 1.

Results

Clinical outcomes

Hardwicke and colleagues’ review3 identified RCTs comparing times of palatal surgery conducted by Ysunza and colleagues6 and Williams and colleagues.4 Since that review, the Scandcleft Consortium11 has reported on three surgical trials (Scandcleft 1, 2 and 3) conducted in parallel in 163, 162 and 154 infants respectively. Only Scandcleft 1, reported by Willadsen and colleagues,12 compared palatal surgery at different ages. In 2019 Yeow and colleagues8 compared timings of palatal surgery in 76 infants with isolated cleft palate. The details of these four RCTs, that investigated surgical-related outcomes following different surgical timing for palatal repair and the corresponding VP insufficiency (VPI) rates quoted at a variety of ages, are given in Table 1.

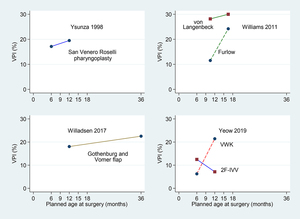

All patients in Ysunza and colleagues’ trial received San Venero Roselli (SVR) pharyngoplasty and all those in Willadsen and colleagues’ trial received Gothenberg and Vomer flap hard palate closure. In contrast, Williams and colleagues’ trial compared von Langenbeck and Furlow palatoplasties, while Yeow and colleagues’ trial compared Veau-Wardill-Kilner (VWK) palatoplasty with two-flap (2F) palatoplasty in conjunction with intra-velar veloplasty (IVV), denoted 2F-IVV.

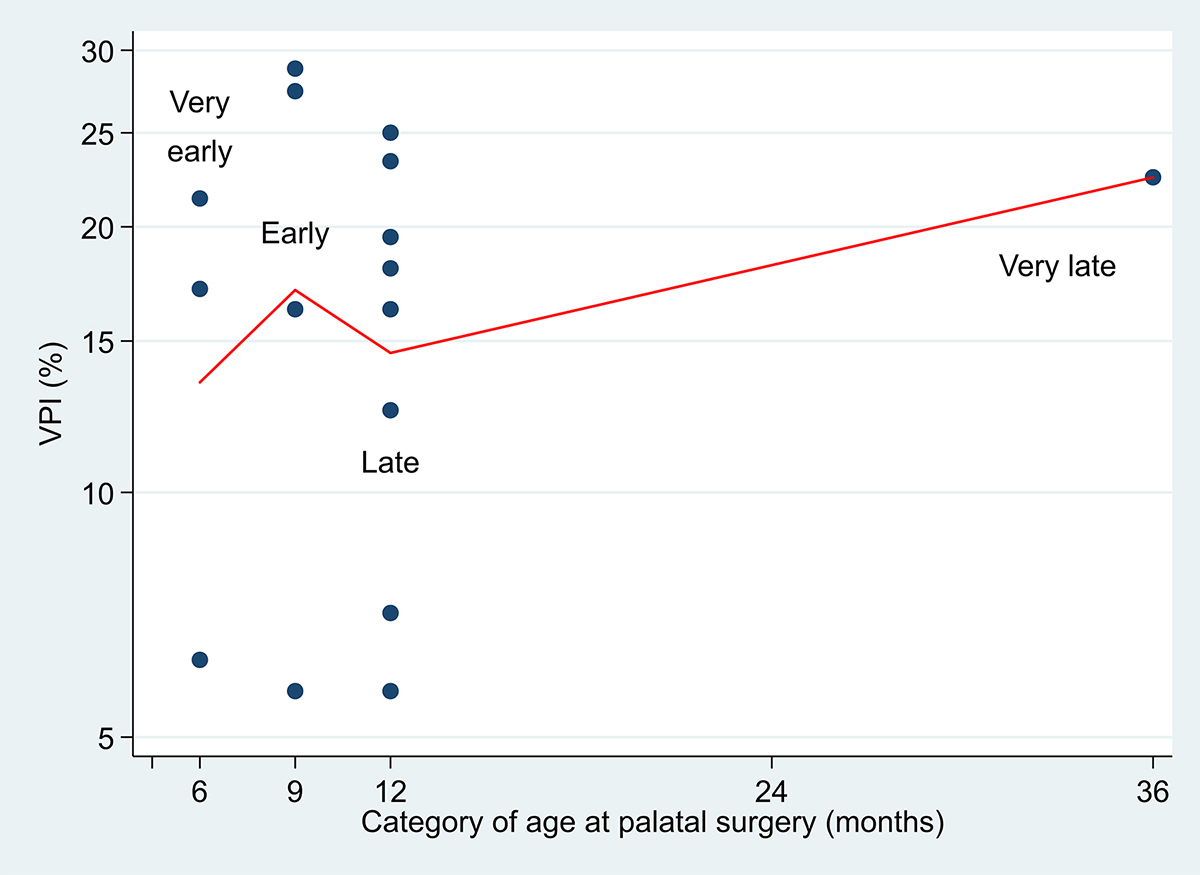

All trials compared ‘early’ and ‘late’ age at palatal surgery (which we classify later into four age categories as ‘very early’, ‘early’, ‘late’ and ‘very late’). Two trials compared outcomes following surgery at six months and 12 months,6,8 and one at 12 months versus 36 months,7 while the fourth considered two ranges of timings of nine to 12 months versus 15–18 months.4 Figure 2 shows the VPI rates by early and late surgery by type of palatal repair for the four RCTs. Apart from 2F-IVV in Yeow and colleagues’ trial,8 late repair was associated with higher rates of VPI.

The difference in VPI rates, together with the associated 95 per cent confidence intervals (CI), between the broad categories ‘early’ and ‘late’ timings are summarised in Table 2. However, the different ages at which VPC was assessed in the four trials prevent a reliable overall synthesis. Nevertheless, all but one (Furlow technique in Williams and colleagues’ trial)4 of the wide CIs in the final column of Table 2 include zero difference (no effect), so there remains much uncertainty with respect to the influence of surgical timing.

Timing (age at palatal surgery)

As we have indicated, the four RCTs used different definitions for ‘early’ and ‘late’ palatal surgery. In practice, despite a specification of six months and 12 months in Yeow and colleagues’ trial,8 Figure 3 shows that the variation at actual age of surgery was quite considerable within each timing group. Thus, the median age of ‘very early’ surgery was close to six months (6.13 m; range 5.32–7.59 m), whereas for ‘late’ the median was 11.43 months (range 10.11–12.87 m) with 82 per cent of 33 infants receiving scheduled surgery before the protocol stipulation of age 12 months.

Williams and colleagues state that ‘Palatal repairs were performed between the ninth and 30th month, with a mean age of 12.85 m (SD=3.3)’. The summary data suggest a skewed distribution towards the lower age at surgery, implying that relatively few children were actually operated at, or close to, 30 months. However, Ysunza and colleagues give no indication of departure from six months (very early) and 12 months (late) scheduling,6 and neither do Rautio and colleagues with respect to 12 months (late) and 36 months (very late) in Scandcleft.14 Figure 4 suggests that the VPI rate does not rise as the age at palatal surgery increases. We note again that the age when VPI assessments were made differs between the four RCTs concerned.

Randomisation

In a clinical trial the usual method is to allocate equal numbers of patients at random to the respective alternatives ensuring balance in the patients recruited by the end of the trial. In general, equal numbers in each group are statistically the most efficient. Only Yeow and colleagues give details of their randomisation process and, although the trial closed prematurely, the numbers in the four groups are close to equal.8 This appears to be the case for the two groups in Rautio and colleagues’ trial,14 less so for Ysunza and colleagues’ trial6 and far from the case for Williams and colleagues’ trial.4 No explanation is provided for the large disparity (ranging from 35 to 51) between infant numbers in the eight groups of Williams and colleagues’ trial.4 As Rautio and colleagues14 used dice to generate the randomisation (and opening of sealed envelopes to reveal the allocation), the close proximity of the numbers in each group (83 and 80) seems fortuitous.

Current standards would tend to proscribe the use of dice for generating the randomisation list and the use of sealed envelopes for implementation. As stated by Suresh, ‘it is better to use […] computer programming to do the randomization’15 particularly for large trials and those of a complex design. Additionally, some regulatory bodies overseeing RCTs insist that the randomisation sequence must be reproducible.

Although numbers are small, one consequence of randomising the infants when six months of age to all four groups in Yeow and colleagues’ trial was that although all 36 allocated palatal surgery at six months received their surgery close to that time, among the 40 allocated to the ‘late’ 12 month group, seven (17.5%) withdrew from the trial before the scheduled surgery could be activated. Furthermore, as Figure 3 indicates, palatal surgery was conducted as early as 10 months of age in this 12 month group. It cannot be deduced whether comparable delays and losses occurred in the other three RCTs.

Trial size

The period covered by this review extends over 20 years during with 782 infants recruited to address the particular role of age at palatal surgery with respect to VPC at a later age. Of these patients, results from 655 (84%) have been reported. Nevertheless, it appears that no firm inferences can be drawn from the resulting data so a truly evidence-based conclusion remains elusive. If we take the results from the four RCTs considered for VPI with ‘early’ as opposed to ‘late’ palatal surgery, Table 3 gives the corresponding sample sizes required for a randomised parallel group trial if these finding were to be anticipated in future trials.

Critically, the size of trial depends on the anticipated effect size (the larger the effect size, the smaller the trial) and on the prevalence of VPI (the binary variable).16 Although the effect size from Yeow and colleagues’ trial8 is smaller than that of Williams and colleagues’ trial,4 the possible confirmatory trial is smaller as the VPI rate for ‘early’ is lower (9.4% as compared to 21%). It is clear from Table 3 that the trial sizes are too large to permit the possibility of any of these confirmatory trials being conducted.

However, Williams and colleagues’ trial4 indicates that VPC is assessed on an 11 point scale graded from 0 to 10 with scores ranging from three to 10 interpreted as being indicative of VPI. Alternatively, Lohmander and colleagues17 have suggested a seven point categorical scale which they subsequently collapsed to a three point classification in their Table 4. In general, if a trial endpoint is defined as an ordered categorical variable, the corresponding sample sizes tend to be smaller than if a binary endpoint is concerned.

Lohmander and colleagues17 reported the results of VPC rates categorised on a three point scale as ‘incompetent’ (VPI) (23.9%), ‘marginally incompetent’ (34.8%), and ‘competent’ (41.3%) in 339 five-year-old infants with repaired cleft palate. We assume a RCT is planned with the aim of reducing VPI levels in infants who have ‘late’ surgery (25%) to a lower rate with early surgery. Then, with a binary endpoint with two-sided test size 5 per cent and power 80 per cent for different (reduced) rates for early (20.0%, 17.5% and 15.0% VPI), the corresponding sample sizes are given in Table 4. These calculations suggest the RCT will range in size from 500 to more than 2000 patients depending on the planning assumption made.

However, using the sample size methods16 concerning a three point categorical scale variable, Table 4 shows for VPI that the proportions of ‘incompetent’, ‘marginal’ and ‘competent’ (25%, 35% and 40% respectively) for ‘late’ surgery, with an assumed planning OR=0.75, would potentially improve (to 20%, 33% and 47%) with ‘early’. What is more, the required sample size is approximately half that for the corresponding binary endpoint. This implies that regarding VPC as a categorical rather than a binary variable would reduce the size of any future trial considerably.

Proposed structure of a collaborative RCT with a pragmatic design followed by a prospective individual patient data meta-analysis

On the basis that the issue of the timing of infant age at palatal surgery remains an open question, it is clear that further trials are required to answer this question, although it is important not to underestimate the challenges that this presents. Indeed, the International Confederation for Cleft Lip and Palate and Related Craniofacial Anomalies Task Force recommended ‘that a prospective international controlled trial is conducted’.18

In the knowledge that there are many individual centres and collaborative groups capable of recruiting substantial numbers of infants with cleft palate/lip anomalies, we propose a pragmatic way forward.

Rather than a single trial, we propose that groups capable of recruiting, for example, 50 eligible infants within a framework of two years, each conduct their own RCT with a view to a future international collaboration to organise a prospective, individual data meta-analysis of these many trials. The possible framework of such a collaboration is summarised in Table 5 which allows individual centres to make specific choices concerning the eligibility of the infants to be included and the surgical options, but with some provisos imposed by the overall design such as an agreed endpoint and how it is to be assessed.

The proposal envisages that the ongoing timing of primary surgery (TOPS) for cleft palate trial by Shaw and colleagues would eventually form part of the prospective meta-analysis.19 Their trial relates to non-syndromic isolated cleft palate participants who have received the Sommerlad surgical technique either at six or 12 months.20 The main outcome variable is VPC at five years but also includes an assessment at three years. Their trial is closed for recruitment with the final follow-up assessments due in July 2020.

Although this article has been written in the context of the unresolved question with regard to surgical timings, the general structure of the proposal allows for a similar approach to be adapted to accommodate other unanswered aspects of cleft management which require RCTs to be conducted. As Bekisz and colleagues conclude, following their review of RCTs in cleft and craniofacial surgery, ‘Our community should consider methods by which more RCTs can be performed’.21

Conclusion

The objective of this review article was to review the available evidence from RCTs concerning the age at which palatal repair is best conducted in infants. Our review suggests no firm conclusions can yet be drawn with respect to the rates of later VPC. As a consequence, we outline the structure of a pragmatic RCT as a basis for further investigation of the optimal of age at surgery (or other relevant research questions).

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Financial declaration

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Revised: 23 May 2022

_at_the_time_of_surgery_by_randomised_allocation_*_(_*unpublished_data.jpg)

_at_the_time_of_surgery_by_randomised_allocation_*_(_*unpublished_data.jpg)