Introduction

The definition of a cosmetic procedure varies between groups. The Accident Compensation Corporation (ACC) defines breast reconstruction as a cosmetic procedure,1 while plastic surgeons would define it as ‘restoration’.2 The Medical Council of New Zealand considers breast reduction a cosmetic procedure,3 despite this procedure being performed for predominantly functional reasons.4 Consequently there is a significant cross-over in definitions of surgery for functional and cosmetic reasons. This makes it hard to sensibly characterise the burden of care arising from interventions for cosmetic reasons. The total number of cosmetic surgeries performed in New Zealand is hard to accurately measure due to no reliable reporting stream.

Surgery for appearance or aesthetic reasons is expensive. New Zealanders and Australians may seek this treatment overseas in order to make significant savings, but there are risks involved in travelling overseas for cosmetic surgery. These include the short initial consultation period, the risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE), the dangers of multi-resistant organism infection, the use of unregulated implants and the lack of medico-legal recourse for patients who have an adverse outcome.5 The number of patients who receive cosmetic surgery overseas is unknown, and the numbers who have complications arising from this treatment are not accurately known either. Literature from overseas studies shows a measurable cost in the treatment of complications arising from cosmetic surgery tourism6–8 and reflects the morbidity patients experience from complications arising from surgery in other countries.9 Internationally there are concerns about infectious disease transmission of antibiotic-resistant bacteria from overseas surgeries.10–12 This article attempts to characterise the number of complications arising from cosmetic surgery in New Zealand and in New Zealand-based patients who have had surgery overseas.

Methods

Information was requested from the ACC in New Zealand regarding how many treatment injury claims were received over a five-year period, and how many of these resulted from New Zealand-based procedures versus overseas-based procedures. Information on the subspecialty of the initial treating clinician was requested as well as the types of complications that occurred.

Furthermore, a prospective audit of patients who had sustained complications from cosmetic surgery overseas was also conducted at Middlemore Hospital over a one-year period from 1 March 2018.

Results

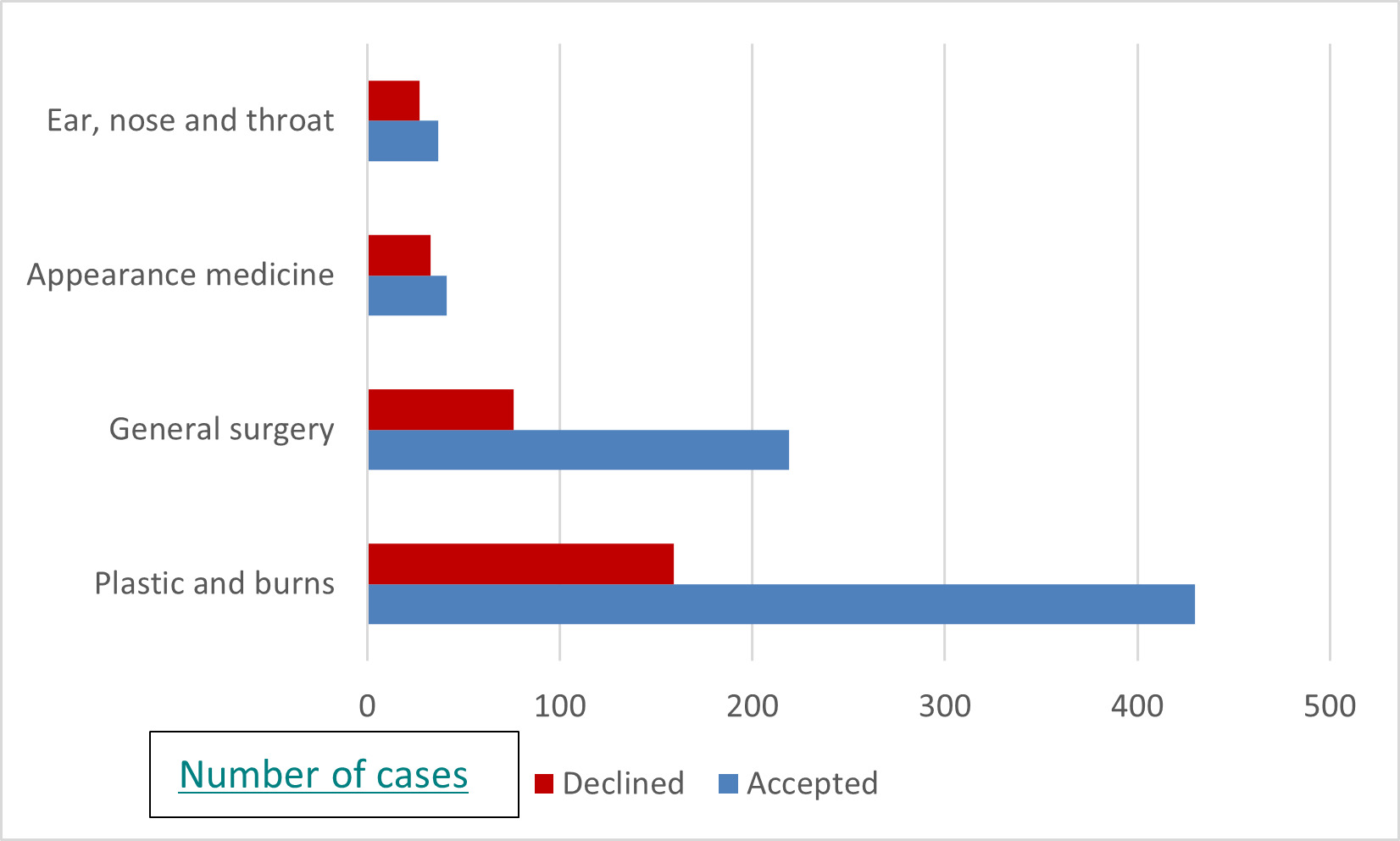

The ACC reported a total of 1048 compensation claims were made over the period 1 July 2014 to 30 June 2019 for complications/treatment injuries arising from cosmetic surgical procedures defined by the ACC as being treatment aimed solely at the ‘aesthetic, cosmetic and wellbeing result’. Of these 1048 claims, 310 were declined, leaving 738 accepted claims. Figure 1 details the number of complications by procedure. Figure 2 shows the type of complication, with infection and haematoma being most common. Figure 3 shows the treatment context under which subspecialty the complication occurred. Just over half had a plastic and burns surgery context, with the next highest being general surgery, then appearance medicine (likely undertaken by GP practitioners) and finally ear, nose and throat. Figure 4 illustrates that when breast reconstruction is removed from the data, most accepted injuries that the ACC agrees to fund treatment for are for surgeries undertaken in New Zealand.

The cost of direct treatment over the five-year period was NZ$4.4 million, with another NZ$1.7 million for compensation due to loss of earnings and NZ$0.3 for rehabilitation. A prospectively collected database was also maintained for a year to capture cases admitted to Middlemore Hospital with complications arising from cosmetic surgery overseas. Twelve patients were identified, of whom nine required admission and surgical intervention. Table 1 details those cases.

Discussion

Defining what constitutes a purely cosmetic surgical procedure compared to a reconstructive or functional procedure is not simple and most plastic surgery operations are a mix of both. The Medical Council of New Zealand considers breast reduction a cosmetic procedure,13 despite this procedure being performed for predominantly functional reasons.4 Insurance companies in New Zealand consider breast restoration following breast cancer a cosmetic procedure and put artificial restrictions on patients’ ability to claim for certain procedures. Thus attempts to quantify the number of complications or treatment injuries arising from cosmetic surgery procedures is challenging due to an exact definition. For those operations that are clearly cosmetic, data are weak to absent as to the total number of those procedures performed in New Zealand.

The closest way of objectively understanding the number of complications from cosmetic surgery is to request that information from the body that provides insurance for when unexpected complications occur. The ACC provides an automatic no-fault accidental injury compensation scheme. If a patient has a complication as a result of surgery and if this is accepted by the ACC as an unexpected occurrence, the cost of subsequent treatment and a proportion of lost income are covered for the patient. A poor cosmetic result does not reach the threshold for cover under the ACC. If the ACC has a concern about the care given to a patient, this will be referred to the relevant disciplinary body, but the main focus is on the patient and their recovery. Consequently, the data for most patients treated in New Zealand who have a complication following surgery are captured by the ACC database. It is more complicated for patients who have their treatment overseas as the ACC will accept a treatment injury only if the surgery has been performed by an appropriately qualified doctor. However, it is not well understood by health professionals in New Zealand that the ACC may cover some patients who have complications as a result of surgery undertaken overseas and so it is thought that many patients do not apply to the ACC to cover their iatrogenic injury. Consequently the data from the ACC regarding the number of patients initially receiving treatment overseas may be under-reported.

ACC data include breast reconstruction and breast reduction as cosmetic procedures. It is interesting to note that if breast reconstruction is removed from the data, there are a third fewer claims to the ACC for complications arising from ‘cosmetic surgery’. Breast reconstruction surgery is fully funded in New Zealand and it is unlikely that patients would travel overseas to seek this care. Once breast reconstruction has been removed from the data, just over 10 per cent of total claims are for treatment initially performed overseas. The percentage of cases declined by the ACC was higher if the surgery had taken place overseas, which most likely reflects either a lack of clear documentation or the fact that the surgery was performed by a doctor whose credentials could not be confirmed by the ACC.

The cases treated through Middlemore Hospital arising from cosmetic surgery tourism show complications that are well recognised but could have been prevented at the time of surgery or been better managed earlier on. Haematomas and wound dehiscence were common and should have been recognised early by the treating surgeon and managed appropriately. Without knowing the true number of patients who have surgery overseas it is hard to determine the incidence or prevalence of complications arising from cosmetic surgery tourism. This single hospital receives one to two cases per month of patients who require impatient care to manage complications arising from cosmetic surgery tourism. For some of these patients, the complication is often present prior to boarding the return flight home. If these patients have a significant infection or dehiscence, they are taking a significant risk when they fly.

There was one patient in this series with an atypical mycobacterial infection, and cross-border transfer of infections is also a critical concern. Patients who undergo surgery in countries where multi-resistant organisms are present are at risk of post-surgery infection with these organisms. Middlemore has noted an increase in the number of Carbapenem-resistant organism (CRO) infections from patients treated in overseas hospitals, which places other immunologically compromised patients at great risk.

Three patients in the series had breast augmentation overseas and subsequent complications. Follow-up for these patients by the operative overseas surgeon did not occur. With the risk of anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL)14 and previous breast implant concerns, patients who are operated on overseas should have appropriate follow-up care. A key issue for ALCL is appropriate consent for the patient, and overseas surgeons who meet the patient for the first time the day prior to the operation would not meet the expectations of appropriate consent that exist in Australasia.15

One patient in the series had a pulmonary embolism (PE). The risk of VTE following major cosmetic surgery is around one per cent.16 Long-haul flights compound the risk of VTE17 and consequently the risk of PE/VTE is high with cosmetic surgery tourism. Patients should be advised not to fly long haul for at least six weeks prior to and six weeks after major cosmetic surgery.18

One main weakness of this article is that we do not know the total of number of patients who travel overseas for cosmetic surgery and then return to New Zealand soon afterwards. The other drawback of this article is the small number of patients that we can observe through a single hospital. This is a similar issue that overseas groups find when trying to assess the impact of complications arising from cosmetic surgery tourism on their own health systems.7,8,10–12 Some articles have attempted meta-analyses of a number of papers documenting treated complications but again the numbers are low and it is hard to assess the true impact.9,19 Furthermore, while we may have some gauge on the medical complications, there is no literature assessing patient-reported outcomes or aesthetic outcomes from cosmetic surgery tourism.

The cost of treating complications arising from ‘cosmetic surgery’ in New Zealand amounts to over NZ$1 million per year—this is covered by the ACC levying premiums on businesses in New Zealand. Patients who choose to have their surgery overseas do not pay a premium and will be cared for in New Zealand if they have a complication, but we do not know the exact number of these patients.

Conclusion

Complications arising from cosmetic surgery are burdensome for the patient and for the community. This article characterises the number of known complications arising from cosmetic surgery in New Zealand and abroad to the best available current data.

Disclosure

The author has no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding

The author received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Revised: August 17, 2020 AEST

.png)

.png)