Introduction

The number of individuals identifying as transgender in Aotearoa New Zealand is not known because previous censuses have asked about gender in a binary fashion (that is, only offering the option for ‘male’ or ‘female’ with no space for further definition).1 Our meta-analysis of the prevalence of self-reported transgender identity in studies worldwide estimates the prevalence as being 355 per 100,000 (after removal of an outlier study), but we acknowledge the difficulty in interpreting such data when study definitions of transgender vary.2 Transgender individuals have increased health needs: some that are directly related to being transgender (for example, hormone therapy), some that can be but are not exclusively related to being transgender (for example, mental health support) and other health needs that have no relation to gender identity (for example, musculoskeletal injuries).3 In addition to health requirements, transgender individuals can face stigma both outside of, and within, the healthcare system.4 The transgender population suffers higher rates of mental illness and suicidality when compared with the general population.5

The process of ‘transitioning’, that is, the journey to presenting as one’s identified gender, can be comprised of many social, hormonal, legal and surgical components and transgender individuals may choose to undertake all, some or none of these steps. These components include but are not limited to gender-affirming surgeries, hormone therapies, changing gender on legal documents and publicly reporting one’s transgender status (referred to as ‘coming out’).6

Masculinising and feminising gender-affirming genital surgeries (phalloplasty, metoidioplasty, vaginoplasty) are a key focus in Aotearoa, partly as a result of the lack of availability of surgeons trained in these surgeries.7 Because of this, there are Ministry of Health guidelines about genital surgery referrals and updates from the gender-affirming (genital) surgery services available.8 These resources do not address referral criteria for referral for other gender-affirming surgeries, such as feminising breast augmentation, masculinising chest reconstruction, hysterectomy, salpingo-oophorectomy, orchidectomy, facial feminisation or laryngeal shave; it is simply advised that these decisions are the responsibility of the local district health board (DHB).9 Information about which services are offered in which DHB has been published by the Gender Minorities Aotearoa (GMA) group. This information was gathered by contacting each DHB in Aotearoa; however, not all DHBs have responded, and the information available does not show waiting times, numbers awaiting surgery, criteria or any further details.10

Secondary care physicians in Aotearoa have incomplete knowledge of the full range of services available to transgender patients.11 There have been no studies that looked at Aotearoa public perception on the availability of breast surgeries. The purpose of this study was to examine public discourse and opinion on the availability and funding of breast surgeries for transgender individuals in Aotearoa. These surgeries are often colloquially referred to as ‘top surgeries’ and include both masculinising and feminising procedures.12,13

Methods

Qualitative approach

This type of study question is best suited to a qualitative research approach, as qualitative methods delve into rich and complex data, allowing for inclusion and synthesis of multiple opinions and perspectives.14 In qualitative research, study data is formed by conversation and discussion, in lieu of numerical data used in quantitative research.

Data collection

Analysis of text-based public discourse was chosen as it allowed for a wide range of opinions to be included, free from the potential of participants being influenced by the presence of a researcher.

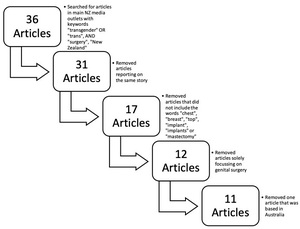

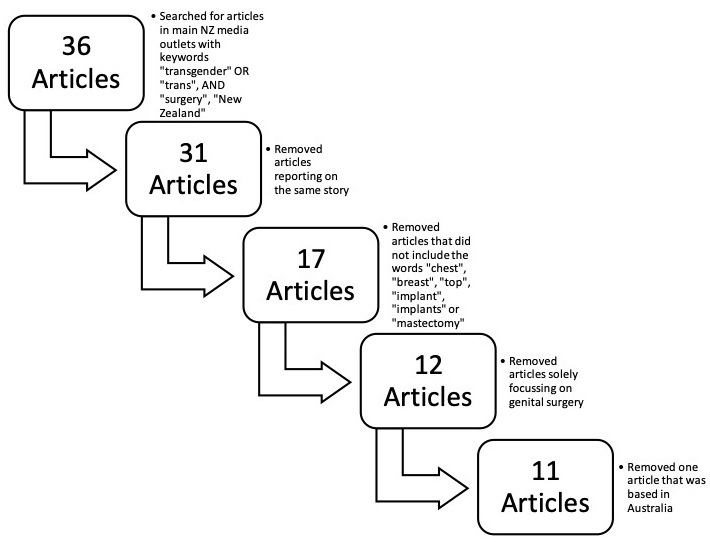

The terms ‘transgender surgery New Zealand’ or ‘trans surgery New Zealand’ were searched in the leading Aotearoa news outlets: The New Zealand Herald, The Dominion Post, the Otago Daily Times, The Press, Stuff and NewsHub.15 Articles were included in the initial sample if they were published between 2015 and 2020, available online and text-based (that is, articles solely in video format were not included). This initial process identified 36 articles. Removing articles that reported on the same story left 31 articles. The articles were then reviewed for their applicability to the top surgery context and were removed if they did not contain the words ‘chest’, ‘breast’, ‘top’, ‘implant’, ‘implants’ ‘mastectomy’ or ‘boob’, leaving 17 articles. Articles focusing only on genital surgery were removed, leaving 12 articles, and one article was removed for being about an Australian transgender individual, therefore not covering any aspect of the Aotearoa experience. This left 11 articles, which were included in the qualitative analysis.

The full text of each article was extracted, in addition to any comments, and the data analysed.

Data analysis

NVivo16 was used for qualitative data analysis. Using a general inductive thematic analysis approach, all of the ideas, concepts and topics mentioned in the articles were coded. Each code was reviewed and grouped into overlapping ideas.17 Each group was repeatedly reviewed to reduce redundancy and repetition and analysed to establish the core driving principles and overarching ideas expressed. The articles were aggregated and re-read, then named. These named aggregations are the themes seen in the final model.17 The model was discussed and reviewed by the secondary reviewer, and a final model was agreed upon.

Potential for bias

Qualitative analysis is by nature subjective, as it relies on the individual interpretation of information rather than a specific metric. These data were initially analysed by the primary researcher and discussed with the secondary researcher, so the findings will be influenced by the researchers’ backgrounds and viewpoints. The primary researcher is a cisgender (that is, a person identifying with the gender assigned to them at birth) female with no lived experience as a transgender individual, and the secondary researcher is a transgender male.

Results

Articles included

The process of data exclusion resulted in 11 final articles being selected (Figure 1).

Themes

The 41 topics/ideas covered in the data were refined and reduced to four themes: public funding, [trans] experiences, [trans] issues amenable to intervention and [trans] issues not amenable to intervention (Figure 2).

Public funding

Where public comments were available, the subject of publicly funded gender-affirming surgery was debated. Heated debate occurred both for and against. The reasons against public funding were varied, including from those who oppose gender transitioning as a whole and those who support transgender individuals but are against interventions they believe to be solely cosmetic procedures. The sentiments expressed in the latter group focused on the limited availability of healthcare funding and resources, and the belief that other surgeries would be more deserving of these resources.

I [am] not against gender re-assignment surgery but I am DEFINITELY against going through the public system and expecting the taxpayer to cover the bill. That’s not what the public health system is there for. Comment

Those in favour of public funding took various approaches. Some took the stance that, since the transgender population has a high rate of mental illness, funding for surgeries would likely have a net benefit, given the potential for reduced demand for psychiatric services and suffering longer term.

But what if not being comfortable in your body increased your likelihood of suicide 10-fold? I’d gladly put my taxes toward a facelift if it was going to SAVE YOUR LIFE. Comment

Others voiced support as part of a wider belief that society should work towards improving the lives of the transgender population, and that gender-affirming surgery is a natural continuation of this support. A variation on this was the acknowledgement that the decisions on which surgeries should and should not be funded are multifaceted, complex and perhaps unsuitable for heated, value-based public debate.

Perhaps a better parallel is a woman needing reconstructive surgery after breast cancer? Unless you’re a bigot, how do you draw the line between her and someone needing their breasts removed as part of gender reassignment surgery? Comment

Many transgender individuals reported either having to spend their own money (or money raised via fundraising platforms) on gender-affirming surgeries, either in Aotearoa or overseas. These options are costly and unobtainable for many.

Experiences

Although the articles and comments were about different individuals, there were many shared trans experiences. These included coming out, having to change identification documentation and having to find appropriate medical care. Some further experiences shared by some but not all individuals were being misgendered (that is, being mistaken for their assigned-at-birth gender), having the wrong pronouns used, being referred to as an object rather than a person, bullying, being ‘outed’ (that is, having their trans status revealed against their will) or experiencing discrimination from healthcare providers.

A woman explained to me exactly what to expect in my transition, and that I would struggle to find a doctor to help me. Article text

Having the incorrect gender on a birth certificate can pose problems for transgender children … it automatically outs a child at a school when they see he has a male name but female gender. Article text

Issues amenable to intervention

Many of the issues experienced by transgender individuals mentioned were those that could be addressed with healthcare interventions. These range from surgical interventions, such as mastectomy to give the confidence to go swimming, taking hormones for a range of mental and physical effects, to psychiatry services to support mental health needs.

However, there are still many things that I’d like to enjoy in life that I am not able to at the moment, such as going out to the beach or going for a swim with my friends, having a bath with my girlfriend or even just sleep with no top on in the heat of summer. There’s an easy fix for that which is a chest reconstructive surgery (bye bye boobies) which is sadly no longer government funded in New Zealand and medical insurers view it as cosmetic surgery. Article text

Some articles focused on just how much benefit can be achieved from intervention.

At the moment, I’m feeling amazing. I’m done with surgeries [after travelling to Thailand for top surgery] for the time being, aside from having laser hair removal treatment on my legs. Article text

Other articles mentioned the detrimental effects of not being able to access interventions.

[X] won’t leave the house without wearing his chest binder, though he knows it may be endangering his health. Article text

Throughout these discussions, the potential of a multitude of ways in which the transgender community could benefit from interventions and procedures was made.

Issues not amenable to intervention

Discussion of trans issues was not limited to therapeutic targets; many of the issues faced by the transgender population are founded in stigma, transphobia and intolerance. These issues will not be fixed by surgery, hormones, clothing or hair removal, but can have a devastating impact. There was mention of the increased risk of sexual assault within the transgender and non-binary community.18

A report last month revealed almost half of all transgender and non-binary New Zealanders have been the victims of attempted rape, and 56 percent of respondents said they’d seriously considered attempting suicide. Comment

Some went further in terms of exploring the long-term impacts of lack of acceptance and stigma, including becoming totally withdrawn and socially isolated.

It’s been so hard to find acceptance out there that there are very few of us who are socially able and functioning as members of society. A lot withdraw from the community out of fear. Article text

Discussion

Study design

Strengths

The richness of the data generated by a qualitative approach has been discussed in the methods section above. In contrast to focus groups, interviews and surveys, data gathered from public fora has the advantage of being free from the potential for responses to be influenced by researcher input.14 Furthermore, the public setting is well suited to addressing the study aim of examining public discourse and opinion on the availability and funding of breast surgeries for transgender individuals in Aotearoa.

Limitations

Qualitative research prioritises depth of data over breadth of responses, and for this reason it is not able to be generalised. There may be many perspectives missing from this data, and it is possible that the opinions expressed publicly (and therefore included) are the outliers of the range of public opinions.

Many individuals choose not to share their opinions in a public setting, and so to fully explore some of these themes, a series of focus groups or interviews may have allowed for deeper discussion in a safe setting.

General inductive thematic analysis uses the researcher(s) as the lens through which the data is interpreted and refined, creating the opportunity for bias to arise.17 This study would have benefited from more reviewers in the analysis process, including more transgender reviewers – this would have brought a wider breadth of perspectives from which to interpret the data. The researcher bias must also be acknowledged in the final presentation of the data, as the representative quotes chosen for each theme are influenced by researcher interpretation.

This study was limited to traditional news media outlets and did not include social media (for example, Twitter, Facebook, Reddit). Social media sources are algorithm-based and have been shown to perpetuate confirmation bias.18 The biases of social media discourse can be mitigated from a data collection perspective,19 but this process would result in data that are not directly comparable to those collected from the news articles. The lack of social media data is a limitation of this study, as social media has a growing importance in public discourse.

Findings

The themes discussed show that transgender issues in Aotearoa are a source of anguish among the transgender community and heated debate within the wider population. While there is some discussion of top surgery access in Aotearoa, most articles have either a wider focus on the transgender experience as a whole or a narrow focus on genital gender-affirming surgery.

When top surgery is discussed, it is portrayed as a means of increasing self-esteem and allowing trans individuals to feel comfortable in their bodies. When the public funding of gender-affirming top surgery was commented upon, there was no clear pathway—each DHB has its own process, making access geographically dependent. Some individuals even referred to self-funding as being liberating in that it removed uncertainty, which is a luxury that not all patients can afford. These inconsistencies are further compounded by the difference in doctors’ understanding and acceptance of trans issues.

Some trans individuals self-funded gender-affirming top surgeries, either in Aotearoa or overseas. With COVID-19 currently limiting international travel,20 there are both geographical and financial barriers limiting access to important interventions.

It is important to note that the data gathered did not include the experiences of those who identify as non-binary or gender non-confirming (meaning their gender identity is neither ‘male’ nor ‘female’). Some of these individuals identify as being part of the transgender sub-group of the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, questioning, intersex, asexual, or other sexuality and gender-diverse identities (LGBTQIA+) community.21 Both non-binary and gender non-confirming people may also opt to have top surgery.13 While this was not explored in the mainstream media sources gathered, we acknowledge that non-binary and/or gender non-conforming individuals face many of the same challenges as transgender individuals, as well as the additional challenge of not having their voices or stories heard.21

A further component of transitioning not discussed is meeting with a clinical psychologist for a readiness assessment. Ordinarily this is in relation to starting hormone replacement therapy (HRT), but can also cover topics including, but not limited to, future surgeries an individual may want to have as part of their transition.22 As a part of this process, individuals are diagnosed with gender dysphoria (that is, psychological distress due to incongruence between assigned sex [at birth] and gender identity),23 which allows them access to gender-affirming healthcare (although services offered vary between DHBs).

In health sciences research regarding transgender experiences, it is important to acknowledge the Trans Wretchedness Theory.24 This is the phenomenon in which health research and media portrayals of trans issues focus on negative outcomes which can provide ammunition for sensational reporting, affirming the views of prejudiced members of the population. This affirmation bias fuels transphobia, which can further perpetuate negative health outcomes in the transgender population as a result of stigma.24 In the hope of mitigating this, and in response to the results of the analysis, we recommend the Ministry of Health consider releasing guidelines on the funding of top surgery to provide clarity and reduce frustration within the transgender, non-binary, and gender non-conforming community.

Conclusion

The public discourse around top surgery for transgender individuals is mixed. While most articles around gender-affirming surgery in Aotearoa focus on genital surgery, there is still some discourse around top surgery. Transgender individuals refer to top surgery as a means to fit in to society, to be able to participate and to enjoy their bodies. Some members of the public strongly oppose public funding for any gender-affirming top surgeries, citing these procedures as being purely cosmetic, whereas others are in favour of public funding, seeing gender-affirming surgeries as empowering and lifesaving. While the process for funding genital gender-affirming surgery is Aotearoa is transparent (albeit with a long waiting list), there are no clear guidelines on the process of funding top surgery. The Ministry of Health should release clear criteria for the funding of top surgery across Aotearoa, to relieve some of the burden of uncertainty and confusion.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding declaration

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Revised: January 24, 2022 AEST