Introduction

This text and accompanying video addresses a selection of major cases in the head and neck region with reconstructive tips to broaden the surgeon’s scope when closing major oncological defects—offering an alternative to some microsurgical procedures.

Major defects in the head and neck region become a testing proposition whatever the surgeon’s experience. Standard microvascular reconstructive procedures have a universal appeal, or necessity, in most major units around the world. There are certain issues in head and neck surgery, that is, the scalp, where microvascular reconstruction is the pre-eminent method for repair.

However, the experience of the head and neck service at Peter MacCallum Cancer Institute using the keystone perforator island flap (KPIF) demonstrates the major contribution this technique has made in simplifying an alternative repair for oncological defects.

The various regions of the head and neck have their own specific application of this technique where the dermatomal, aligned with neurovascular support and a fascial-lined base, is the method for closure. Hypervascularity—a presumed sympathectomy effect evident in all KPIF reconstructions. This allows for closure under tension which is routinely contraindicated in all reconstructive procedures. The KPIF illustrates how this rule can be broken because the subfascial plexus is perforator based and not reliant on the subdermal plexus.

This ‘How to do it’ lists a range of cases, supplemented by video discussion, that explain the refinements of the KPIF technique to specific sites of the head and neck with a focus on the elderly, for whom the more simple procedure used, the better.

Fig 1.Edited version of the surgical illustration by F C BEHAN as a teaching tool

Principles

The KPIF has been in service in the reconstructive field for over 25 years since its initial publication.1 It can be applied all over the body and when the basic rules of island flap elevation are observed, the successful outcome of these neuro-dermatomal flaps becomes evident.

Blood supply is based on random perforator design located within various sites of dermatomal mark-out over the body (bypassing the need for angiographic confirmation, with obvious cost saving implications). The mark-out of the neuro-dermatome delineates the nerve supply at the cutaneous level2 and follows the principle that, if nerve supply is intact, there must be a supportive blood supply. (In paraplegics, the blood supply is intact but the complications of wound healing are staggering when one part of the equation has been eliminated, that is, no nerve supply but intact blood supply.)

From this simple principle (and where the design of the neurovascular island flap within the dermatomal precincts is based on a random axial and perforator) we have classified the KPIF as an angiotome. Leaving one-third attachment of the undermine island flap is a basic pre-requisite for successful completion.

Characteristics

The characteristics of the KPIF technique can be represented by a simple acronym, PACE:

PACE

| P |

Pain: The KPIF is relatively pain free based on observational findings that any surgical wound is pain free on either side of the incision which recovers. The keystone design are similar to a linear surgical wound but quadrilateral in shape. |

| A |

Aesthetics: The Gillies principle of using ‘like-for- like’3 is respected and repeated when the KPIF is applied in reconstruction. The adjacent tissue also reflects Gillies statement that ‘the next best tissue is the next best tissue’. |

| C |

Complications: From a healing point of view, complications are fairly uncommon. I use the word ‘prime’ to indicate the VY apices and these are the points of maximal tension. Hence, locking mattress sutures at these tension sites must stay in place for at least three weeks to minimise wound breakdown. |

| E |

Economics: The economics of an expeditious procedure needs no elaboration and is clinically preferrable to hour long efforts when employing microsurgical techniques. All the KPIF cases I have done to date have been completed without the use of preoperative angiography—another cost saving. Even Doppler localisation is dispensed with and the design of the flaps around the neurodermatomal axes is the lifeline for the successes illustrated. Flaps based on a nerve supply (dermatomes) are more reliable than those based on a vascular axes which the KPIF illustrates. |

When the PACE acronym is applied, the KPIF technique is a respectable alternative to microvascular surgery, particularly in the elderly, with minimal returns to theatre for vascular impedance problems4 which are not infrequent in microvascular reconstructions. A timeframe in theatre of one to two hours for any major repair using the KPIF technique also augers well for a suitable outcome when theatre timeframes for microvascular surgery may be longer.

Cases

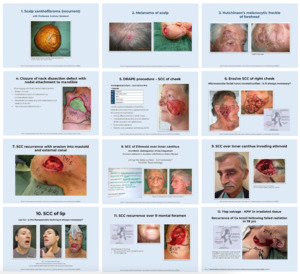

In the audio visual files linked to this article, I use 12 cases with a focus on the elderly (Table 1) to illustrate how the KPIF technique can be refined to help teach these principles. Case 10 illustrates the value of KPIF lip reconstruction compared with microsurgical pronator quadratus techniques.5 Case 13 lists a complication (Table 2).

Table 1.Summary of cases using the KPIF technique in head and neck reconstruction with a focus on the elderly

| Patient |

Site of path |

Size of defect |

Dermatomal mark out |

Angiotome supply |

Complications |

| 1. 55-year-old female |

Malignant fibrous Xanthoma of vertex of scalp |

8 x 8 cm |

Sup. temporal artery |

V3 dermatome |

Nil |

| 2. 60-year-old male |

Malignant melanoma of scalp over parietal region |

4 x 4 cm |

Based on post auricular artery |

C2 dermatome |

Nil |

| 3. 72-year-old male with level II malignant melanoma HMF (R) forehead |

(R) forehead |

6 x 8 cm |

V2 region of (R) cheek islanded to incorporate temporal extension rotated to fill defect |

Infra-orbital artery of V2 |

Nil |

| 4. 85-year-old male |

Recurrent SCC in submandibular triangle with bony attachment to the mandible |

7 x 8 cm |

Based on random supraclavicular perforators |

C2/3 dermatomes |

Nil |

| 5. 55-year-old female (five operations for clearance) |

(L) cheek |

8 x 5 cm |

C2/3 dermatome

(cervico submental angiotome KPIF |

Perforators from the alignment of sternomastoid muscle |

Nil |

| 6. 73-year-old male with SCC (R) cheek full of maggots |

(R) cheek

Sacrificing the facial nerve (V11) |

9 x 5cm |

Cervico submental island flap based on perforators |

C2/3 dermatomes using sternomastoid perforators for KPIF |

Self-discharged |

| 7. 70-year-old male dialysis patient SCC (R) ear |

|

8 x 6 cm |

KPIF using C2/3/4 dermatome |

Sternomastoid perforators over sternomastoid |

Ectropion |

| 8. 94-year-old female with SCC of ethmoid |

|

5 x 4 cm |

V2 dermatome using infraorbital and supraorbital perforators for the keystone design |

|

Mild ectropion |

| 9. 62-year-old male with BCC (L) innercanthus |

|

5 x 4 x 3 cm |

V2 |

|

Mild enophthalmos |

| 10. 35-year-old male with CA of the lip and 75 per cent loss |

Bilateral submandibular gland removal |

5 x 3 cm |

KPIF using V3 dermatome |

Blood supply from facial artery and V3 dermatome

Mucosal island from intra-oral lining |

Nil |

| 11. 73-year-old female with CA of lower lip with recurrence over infra orbital foramen |

Vermilion retained |

8 x 8 cm |

KPIF using V3 dermatome |

Random facial vasculature of facial artery and V3 dermatome |

Mild oral dribbling |

| 12. 78-year-old female with CA tonsillar fossa recurrence following XRT |

(L) supra-clavicular mass |

20 x 4 cm |

V2 dermatome |

Facial artery (L) cheek with island flap reconstruction |

Minor separation of the (L) ear wound with premature removal of sutures |

R = right, L = left, BCC = basal cell carcinoma CA = cancer, C2/3/4 = dermaterms, HMF = Hutchison’s melanomotic freckle, KPIF = Keystone Perforator Island Flap, SCC = squamous cell carcinoma, V2 = trigeminal nerve (maxillary division) V3 = trigeminal nerve (mandibular division), XRT = radiotherapy

Table 2.Complication

| Patient |

Site of path |

Size of defect |

Dermatomal mark out |

Angiotome supply |

Complications |

| 1. 56-year-old female with SCC tonsil XRT with recurrence overlying (R) neck carotid complex |

(R) supraclavicular

area in irradiated

field |

|

Cervico submental KPIF islanded in irradiated tissue to salvage circulatory deficiencies |

|

Fully healed at two weeks but premature removal of some sutures by outside clinic resulted in wound partial rupture—secondary flap reconstructions |

Fig 2.Cases with a focus on the elderly are discussed in the audio visual files linked to this article.

Further reading

-

Behan FC, Wilson JSP. The principles of the Angiotome: a system of linked axial pattern flaps. Sixth International Congress of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. Paris, 24–29. August 1975.

-

Behan FC. The keystone design perforator island flap in reconstructive surgery. ANZ J Surg. 2003;73:112–20. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1445-2197.2003.02638.x PMid:12608972

-

Behan FC, Findlay M, Lo CH. The keystone perforator island flap concept. Sydney: Churchill Livingstone, 2012.

-

Behan FC, Lo CH, Shayan R. Perforator territory of the key–stone flap: use of the dermatomal roadmap. J Plast Reconstr Aesth Surg. 2009;62:551–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjps.2008.08.078 PMid:19046659

-

Behan FC. Surgical tips and skills. Sydney: Churchill Livingstone, 2014.

-

Behan FC, Rozen WM, Azer S, Grant P. ‘Perineal keystone design perforator island flap’ for perineal and vulval reconstruction. ANZ J Surg. 2012;82:381–82. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1445-2197.2012.06021.x PMid:23305061

-

Behan FC. Evolution of the fasciocutaneous island flap leading to the keystone flap principle in lower limb reconstruction. ANZ J Surg. 2008;78:116–17. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1445-2197.2007.04382.x PMid:18269468

-

Behan FC. The fasciocutaneous island flap: an extension of the angiotome concept. ANZ J Surg. 1992;62:874–86. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1445-2197.1992.tb06943.x

-

Behan FC, Sizeland A, Porcedu S, Somia N, Wilson J. Keystone island flap: an alternative reconstructive option to free flaps in irradiated tissue. ANZ J Surg. 2006;76:407–13. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1445-2197.2006.03708.x PMid:16768705

-

Behan FC, Paddle A, Rozen WM et al Quadriceps keystone island flap for radical inguinal lymphadenectomy: a reliable locoregional island flap for large groin defects. ANZ J Surg. 2013;83:942-47. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1445-2197.2011.05790.xPMid:22507632

-

Shayan R, Behan FC. Re the ‘keystone concept’: time for some science. ANZ J Surg. 2013;83:499–500. https://doi.org/10.1111/ans.12303 PMid:24049789

-

Pelissier P, Santoul M, Pinsolle V, Casoli V, Behan FC. The keystone design perforator island flap. Part I: anatomic study. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2007;60:883-87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjps.2007.01.072 PMid:17446152

-

Behan FC, Sizeland A, Gilmour F, Hui A, Seel M, Lo CH. Use of the keystone island flap for advanced head and neck cancer in the elderly: a principle of amelioration. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2010;63:739–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjps.2009.01.079 PMid:19332401

-

Behan FC, Rozen WM, Tan S. Yin–yang flaps: the mathematics of two keystone island flaps for reconstructing increasingly large defects. ANZ J Surg. 2011;81:574–75. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1445-2197.2011.05814.x PMid:22295411

-

Behan FC, Rozen WM, Lo CH, Findlay M. The omega—Ω— variant designs (types A and B) of the keystone perforator island flap. ANZ J Surg. 2011;81:650–52. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1445-2197.2011.05833.x PMid:22295410

Acknowledgements

Audiovisual presentation complements this paper. Produced for the author by Woodrow Wilson Clinical Imaging.

Patient consent

Patients/guardians have given informed consent to the publication of images and/or data.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Supplementary online material

http://www.youtube.com/channel/UC6-K8MTU6rThPAjTfJGc89w

Updated: June 17, 2021 AEST (reclassified as a feature)

Submitted: April 05, 2019 AEST

Accepted: April 05, 2019 AEST